By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

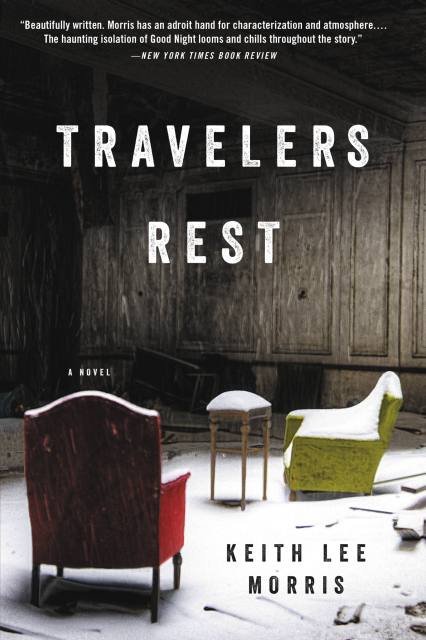

Travelers Rest

A Novel

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 5, 2016

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316335805

Price

$9.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $11.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $20.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 5, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A chilling fable about a family marooned in a snowbound town whose grievous history intrudes on the dreamlike present.

The Addisons — Julia and Tonio, ten-year-old Dewey, and derelict Uncle Robbie — are driving home, cross-country, after collecting Robbie from yet another trip to rehab. When a terrifying blizzard strikes outside the town of Good Night, Idaho, they seek refuge in the town at the Travelers Rest, a formerly opulent but now crumbling and eerie hotel where the physical laws of the universe are bent.

Once inside the hotel, the family is separated. As Julia and Tonio drift through the maze of the hotel’s spectral interiors, struggling to make sense of the building’s alluring powers, Dewey ventures outward to a secret-filled diner across the street. Meanwhile, a desperate Robbie quickly succumbs to his old vices, drifting ever further from the ones who love him most.

With each passing hour, dreams and memories blur, tearing a hole in the fabric of our perceived reality and leaving the Addisons in a ceaseless search for one another. At each turn a mysterious force prevents them from reuniting, until at last Julia is faced with an impossible choice.

Can this mother save her family from the fate of becoming Souvenirs — those citizens trapped forever in magnetic Good Night — or, worse, from disappearing entirely? With the fearsome intensity of a ghost story, the magical spark of a fairy tale, and the emotional depth of the finest family sagas, Keith Lee Morris takes us on a journey beyond the realm of the known. Featuring prose as dizzyingly beautiful as the mystical world Morris creates, Travelers Rest is both a mind-altering meditation on the nature of consciousness and a heartbreaking story of a family on the brink of survival.

The Addisons — Julia and Tonio, ten-year-old Dewey, and derelict Uncle Robbie — are driving home, cross-country, after collecting Robbie from yet another trip to rehab. When a terrifying blizzard strikes outside the town of Good Night, Idaho, they seek refuge in the town at the Travelers Rest, a formerly opulent but now crumbling and eerie hotel where the physical laws of the universe are bent.

Once inside the hotel, the family is separated. As Julia and Tonio drift through the maze of the hotel’s spectral interiors, struggling to make sense of the building’s alluring powers, Dewey ventures outward to a secret-filled diner across the street. Meanwhile, a desperate Robbie quickly succumbs to his old vices, drifting ever further from the ones who love him most.

With each passing hour, dreams and memories blur, tearing a hole in the fabric of our perceived reality and leaving the Addisons in a ceaseless search for one another. At each turn a mysterious force prevents them from reuniting, until at last Julia is faced with an impossible choice.

Can this mother save her family from the fate of becoming Souvenirs — those citizens trapped forever in magnetic Good Night — or, worse, from disappearing entirely? With the fearsome intensity of a ghost story, the magical spark of a fairy tale, and the emotional depth of the finest family sagas, Keith Lee Morris takes us on a journey beyond the realm of the known. Featuring prose as dizzyingly beautiful as the mystical world Morris creates, Travelers Rest is both a mind-altering meditation on the nature of consciousness and a heartbreaking story of a family on the brink of survival.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use