By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

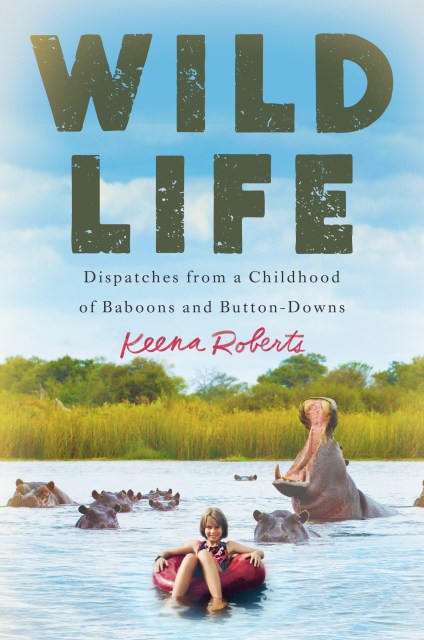

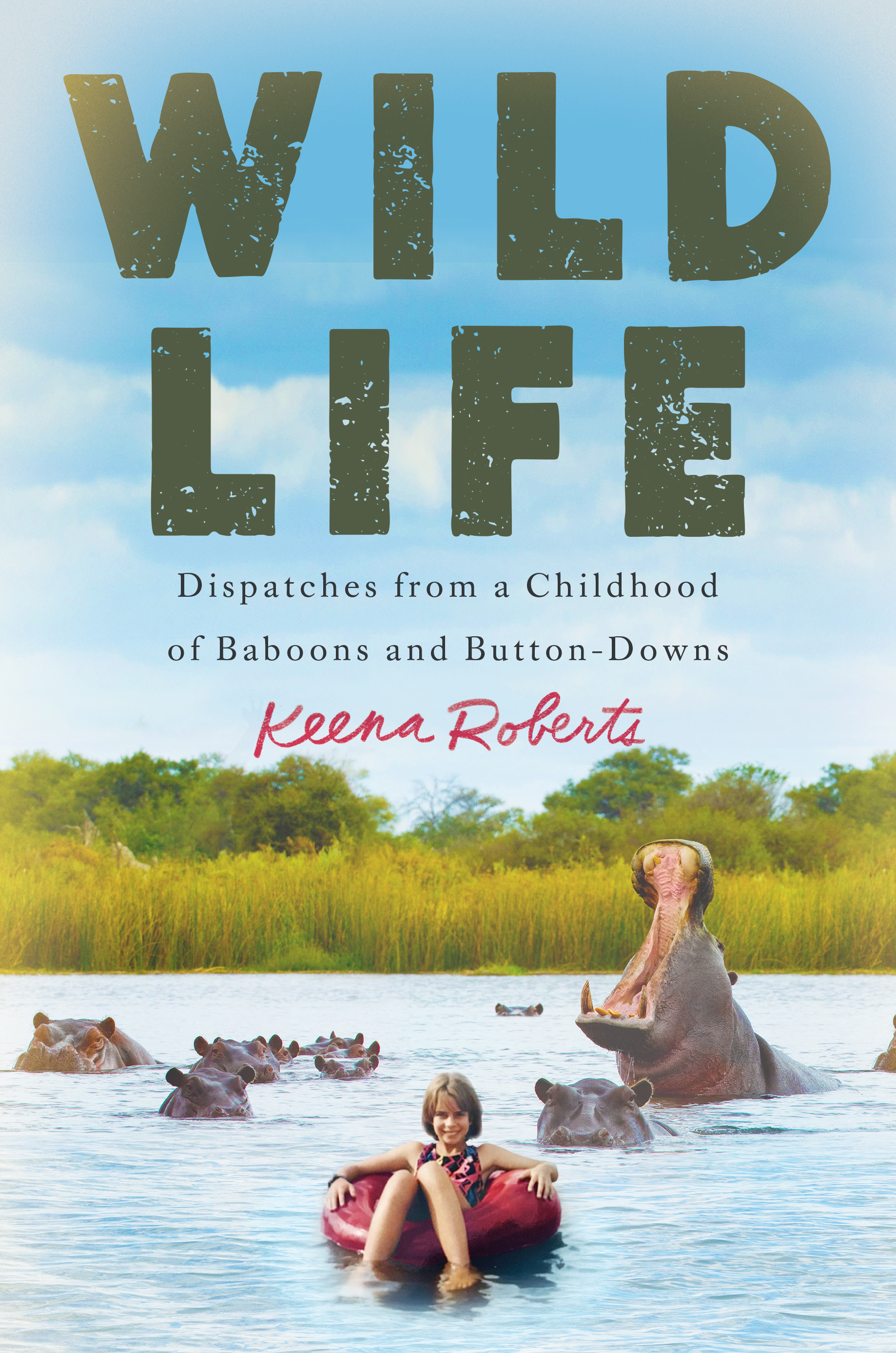

Wild Life

Dispatches from a Childhood of Baboons and Button-Downs

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 12, 2019

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538745144

Price

$14.99Price

$18.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $18.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 12, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight meets Mean Girls in this funny, insightful fish-out-of-water memoir about a young girl coming of age half in a “baboon camp” in Botswana, half in a ritzy Philadelphia suburb.

Keena Roberts split her adolescence between the wilds of an island camp in Botswana and the even more treacherous halls of an elite Philadelphia private school. In Africa, she slept in a tent, cooked over a campfire, and lived each day alongside the baboon colony her parents were studying. She could wield a spear as easily as a pencil, and it wasn’t unusual to be chased by lions or elephants on any given day. But for the months of the year when her family lived in the United States, this brave kid from the bush was cowed by the far more treacherous landscape of the preppy, private school social hierarchy.

Keena Roberts split her adolescence between the wilds of an island camp in Botswana and the even more treacherous halls of an elite Philadelphia private school. In Africa, she slept in a tent, cooked over a campfire, and lived each day alongside the baboon colony her parents were studying. She could wield a spear as easily as a pencil, and it wasn’t unusual to be chased by lions or elephants on any given day. But for the months of the year when her family lived in the United States, this brave kid from the bush was cowed by the far more treacherous landscape of the preppy, private school social hierarchy.

Most girls Keena’s age didn’t spend their days changing truck tires, baking their own bread, or running from elephants as they tried to do their schoolwork. They also didn’t carve bird whistles from palm nuts or nearly knock themselves unconscious trying to make homemade palm wine. But Keena’s parents were famous primatologists who shuttled her and her sister between Philadelphia and Botswana every six months. Dreamer, reader, and adventurer, she was always far more comfortable avoiding lions and hippopotamuses than she was dealing with spoiled middle-school field hockey players.

In Keena’s funny, tender memoir, Wild Life, Africa bleeds into America and vice versa, each culture amplifying the other. By turns heartbreaking and hilarious, Wild Life is ultimately the story of a daring but sensitive young girl desperately trying to figure out if there’s any place where she truly fits in.

In Keena’s funny, tender memoir, Wild Life, Africa bleeds into America and vice versa, each culture amplifying the other. By turns heartbreaking and hilarious, Wild Life is ultimately the story of a daring but sensitive young girl desperately trying to figure out if there’s any place where she truly fits in.

-

"An unusual and fascinating coming-of-age story. . . Wild Life is a page-turner with universal appeal."The New York Journal of Books

-

"The contrast between life in the bush and life in the city, and of how Roberts learns to balance her two selves-the girl in the delta who can do everything adults do and the weirdo who doesn't feel safe in America-is a terrific coming-of-age story. Full of details about field research and bar mitzvahs, what to do when you meet dangerous wildlife or dangerous mean girls, and how reading was her salvation, Roberts' fish-out-of-water story is impossible to put down.""Booklist

-

"Wild Life is a moving, thoughtful memoir of a young woman finding her path. Roberts' frank and witty voice is perfect--she navigates both joy and sorrow with a deft, sure touch, and her descriptions of Baboon Camp are so bright and vivid you can smell the dust. I couldn't put it down."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Times New Roman'}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}Madeline Miller, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Circe

-

"This episodic, warm exploration of identity and culture is both wide-eyed and surprisingly wise...[Wild Life captures] a carefree girlhood among wildlife and a rougher existence at school in Pennsylvania...An immersive narrative that will have readers admiring the author's mostly charming adventures."Kirkus

-

"Roberts's refreshing, upbeat debut is a rollicking memoir of girlhood adventure and matter-of-fact bravery [...] Roberts writes with humor and kindness throughout, especially as she examines white privilege and the cultural differences of the Botswanan [...] Resilient and resourceful, Roberts celebrates an unorthodox life in this endearing memoir."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Times New Roman'}Publishers Weekly

-

"A riveting account of a swashbuckling, lion-dodging, tough-as-nails childhood and also a perceptive examination of how the geographical and cultural fault lines within one person shift and rupture over time. I couldn't put Wild Life down-this book left me hungry for awe."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Times New Roman'}Maggie Shipstead, New York Times bestselling author of Seating Arrangements and Astonish Me

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use