By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

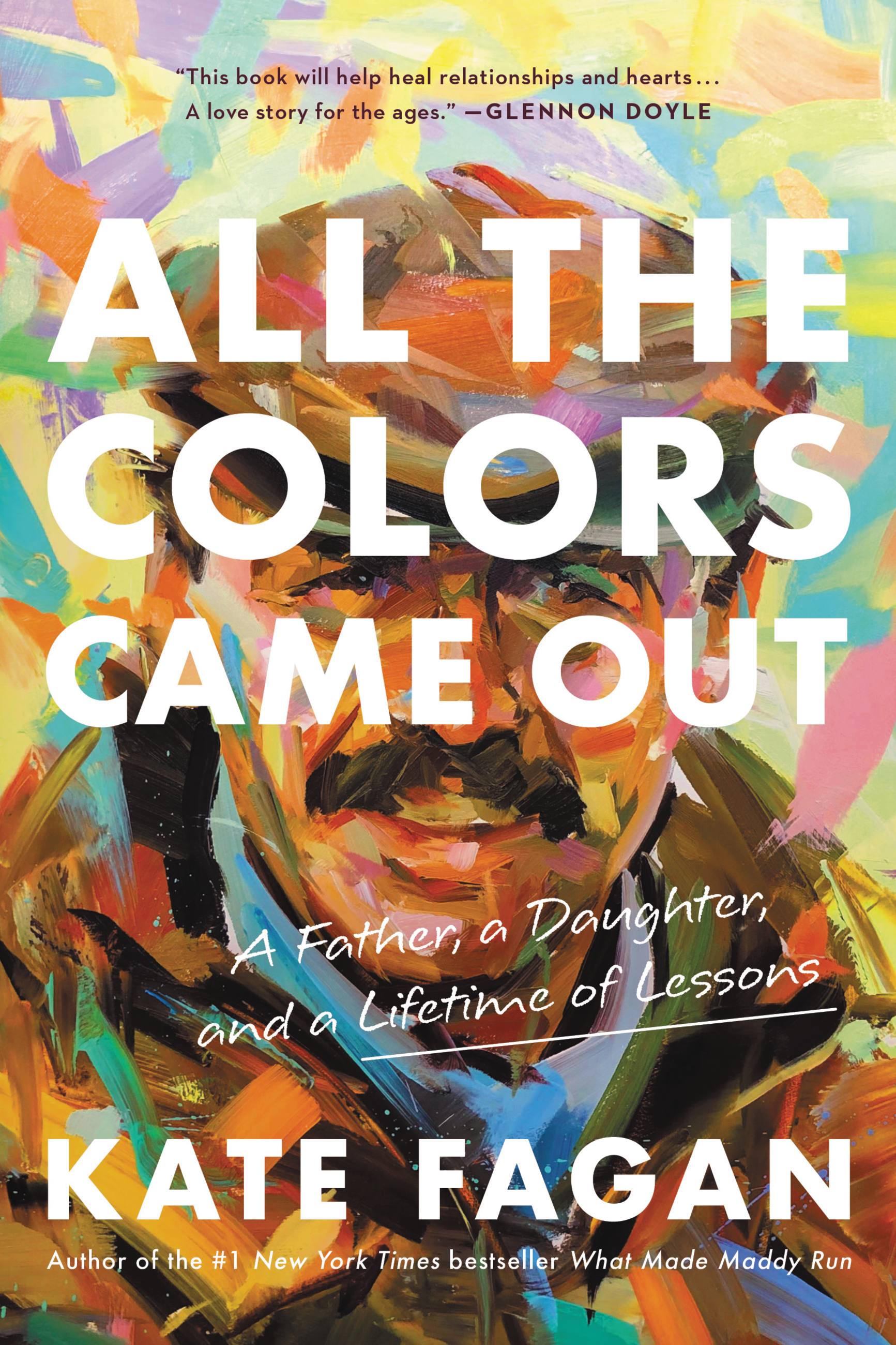

All the Colors Came Out

A Father, a Daughter, and a Lifetime of Lessons

Contributors

By Kate Fagan

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 18, 2021

- Page Count

- 208 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316706902

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 18, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

This "love story for the ages" from a # 1 New York Times bestselling author comes an unforgettable story about basketball and the enduring bonds between a father and daughter that "will heal relationships and hearts" (Glennon Doyle).

Kate Fagan and her father forged their relationship on the basketball court, bonded by sweaty high fives and a dedication to the New York Knicks. But as Kate got older, her love of the sport and her closeness with her father grew complicated. The formerly inseparable pair drifted apart. The lessons that her father instilled in her about the game, and all her memories of sharing the court with him over the years, were a distant memory.

When Chris Fagan was diagnosed with ALS, Kate decided that something had to change. Leaving a high-profile job at ESPN to be closer to her mother and father and take part in his care, Kate Fagan spent the last year of her father’s life determined to return to him the kind of joy they once shared on the court. All the Colors Came Out is Kate Fagan’s completely original reflection on the very specific bond that one father and daughter shared, forged in the love of a sport which over time came to mean so much more.

Studded with unforgettable scenes of humor, pain and hope, Kate Fagan has written a book that plumbs the mysteries of the unique gifts fathers gives daughters, ones that resonate across time and circumstance.

Kate Fagan and her father forged their relationship on the basketball court, bonded by sweaty high fives and a dedication to the New York Knicks. But as Kate got older, her love of the sport and her closeness with her father grew complicated. The formerly inseparable pair drifted apart. The lessons that her father instilled in her about the game, and all her memories of sharing the court with him over the years, were a distant memory.

When Chris Fagan was diagnosed with ALS, Kate decided that something had to change. Leaving a high-profile job at ESPN to be closer to her mother and father and take part in his care, Kate Fagan spent the last year of her father’s life determined to return to him the kind of joy they once shared on the court. All the Colors Came Out is Kate Fagan’s completely original reflection on the very specific bond that one father and daughter shared, forged in the love of a sport which over time came to mean so much more.

Studded with unforgettable scenes of humor, pain and hope, Kate Fagan has written a book that plumbs the mysteries of the unique gifts fathers gives daughters, ones that resonate across time and circumstance.

-

"I really related personally to this book, and I feel that for a lot of women who grew up playing sports and ended up being gay, it [reflects] this special relationship that you have with your dad, where sport becomes an important point of connection."Megan Rapinoe, Vogue

-

“Fagan has done a remarkable service to her father by telling the story of his life with such generosity and to her fellow caregivers by candidly describing the circumstances under which that life came to an end.”The Washington Post

-

“A heartfelt meditation on what matters.”The Boston Globe summer reading feature

-

“The author’s singular talent for relating her internal struggles and growth shines in this exquisite tribute to her father and family, and to the game of basketball.”Library Journal (starred review)

-

"While the world screams for our attention, Kate Fagan arrives, quietly hands us All The Colors Came Out, and we remember what matters. Fagan is an artist, so I knew this book would be brilliant. What I didn’t expect was her gut wrenching and soul cleansing honesty about the complications and confusions of familial love. I finished feeling understood, less alone, and committed to being braver with my own father. This book will help heal relationships and hearts. All the Colors Came Out is a love story for the ages."Glennon Doyle, author of the #1 Bestseller Untamed and the founder of Together Rising

-

“All the Colors Came Out is one of those books that will make you cry on one page and feel like you’ve learned something to improve your life on the next.”Joyce Bassett, Albany Times Union

-

“This book. I read it straight through, barely moving until the last word on the last page. Here is a deeply affecting story about a father and daughter, human failings and human forgiveness, and finding an unflinching heart when you need it most. It is written with such love and honesty you won’t soon forget it.”Sue Monk Kidd, author of The Book of Longings

-

“This is a book about basketball, yes, and fandom and home, and about fathers and daughters, to be sure—about all parents and children, really—but most of all it is a story about the fierce and redemptive power of love.”Wright Thompson, author of Pappyland

-

"Once again, in a story of pain and loss, Kate Fagan manages to find beauty and humanity and write a book that teaches us a great deal about our own lives."Ryan Holiday, #1 New York Times bestselling author of The Daily Stoic and the Daily Stoic podcast

-

"Like many women in my field, I inherited my love for sports from my dad, and the parallels between our bond and the one Fagan recounts here jumped off the page. But All the Colors Came Out isn't just about fathers and daughters--it's about the ways in which human connection shapes identity, and how those ties can be quietly frayed, and then, in the face of devastating adversity, repaired. It's a story of heartbreak and healing, and one that will sit with me for a long time."Mina Kimes, Senior Writer at ESPN and co-host of NFL Live

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use