By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

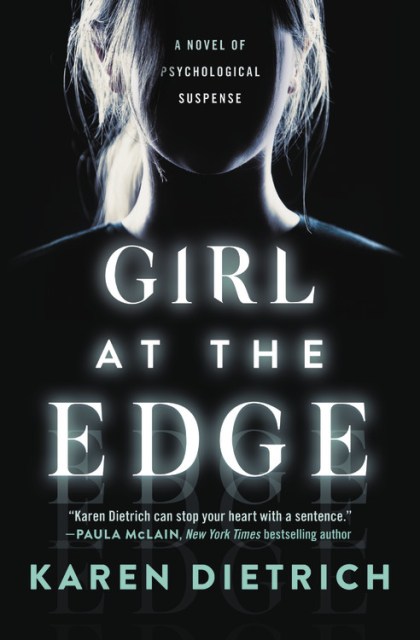

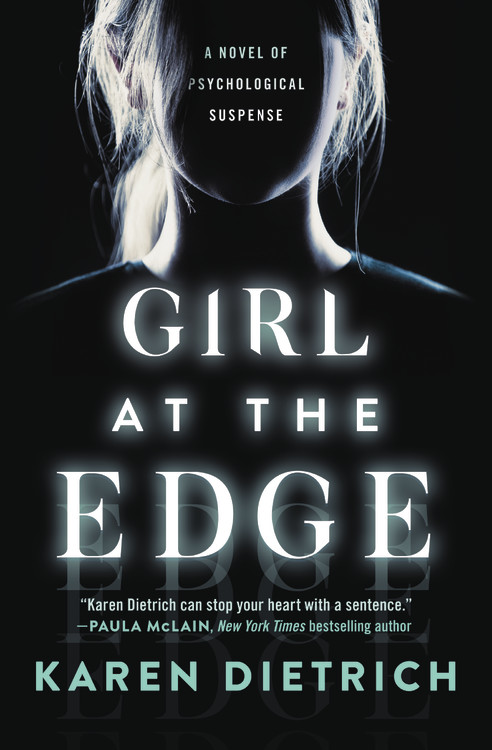

Girl at the Edge

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 3, 2020

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538732939

Price

$15.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $21.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 3, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“Karen Dietrich can stop your heart with a sentence.”

–Paula McLain, author of The Paris Wife

–Paula McLain, author of The Paris Wife

Not a single resident of St. Augustine, Florida, can forget the day that Michael Joshua Hayes walked into a shopping mall and walked out the mass murderer of eleven people.

He’s now spent over a decade on death row, and his daughter Evelyn – who doesn’t remember a time when her father wasn’t an infamous killer – is determined to unravel the mystery and understand what drove her father to shoot those innocent victims.

Evelyn’s search brings her to a support group for children of incarcerated parents, where a fierce friendship develops with another young woman named Clarisse. Soon the girls are inseparable, and by the beginning of the summer, Evelyn is poised at the edge of her future and must make a life-defining choice. Whether to believe that a parent’s legacy of violence is escapable or that history will simply keep repeating itself. Whether we choose it to or not.

-

"Dietrich has a writing style that feels like a breath of fresh air in a genre that sometimes suffers from a sense of sameness, and her characters and their dialogue are exquisitely rendered. A fine psychological thriller."Booklist

-

"The psychological-thriller genre may be packed with books that sound alike, but this one feels fresh - Memorable and disquieting."Winnipeg Free Press

-

"Original metaphors and nice descriptions bolster this extended monologue of a potential killer... Dietrich's assured prose bodes well for the future."Publishers Weekly

-

"Girl At The Edge is a page turner from the very first one to the very end. The statement 'an author has to capture the reader from the very first line' is a perfect fit here with 'My father is a murderer.' Girl At The Edge takes readers into a dark and sinister universe that most of them will never have to encounter."MidwestBookReview.com

-

"Not easy to walk away from after reading the last page. Readers will find Evelyn's inner turmoil and actions haunting, and will likely never view a news story about yet another mass shooting the same way again."JHSeiss.com

-

"Karen Dietrich can stop your heart with a sentence."Paula McLain, New York Times bestselling author

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use