By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

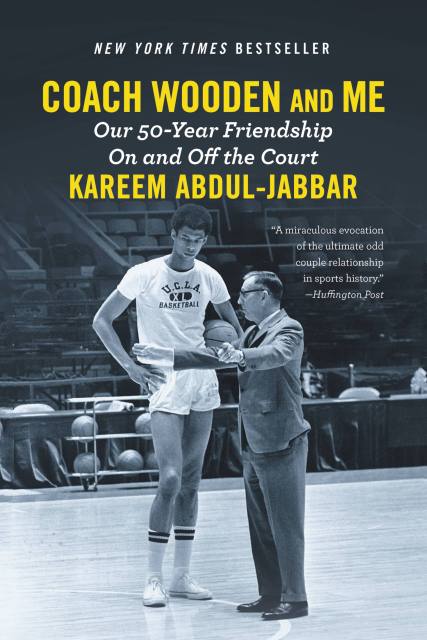

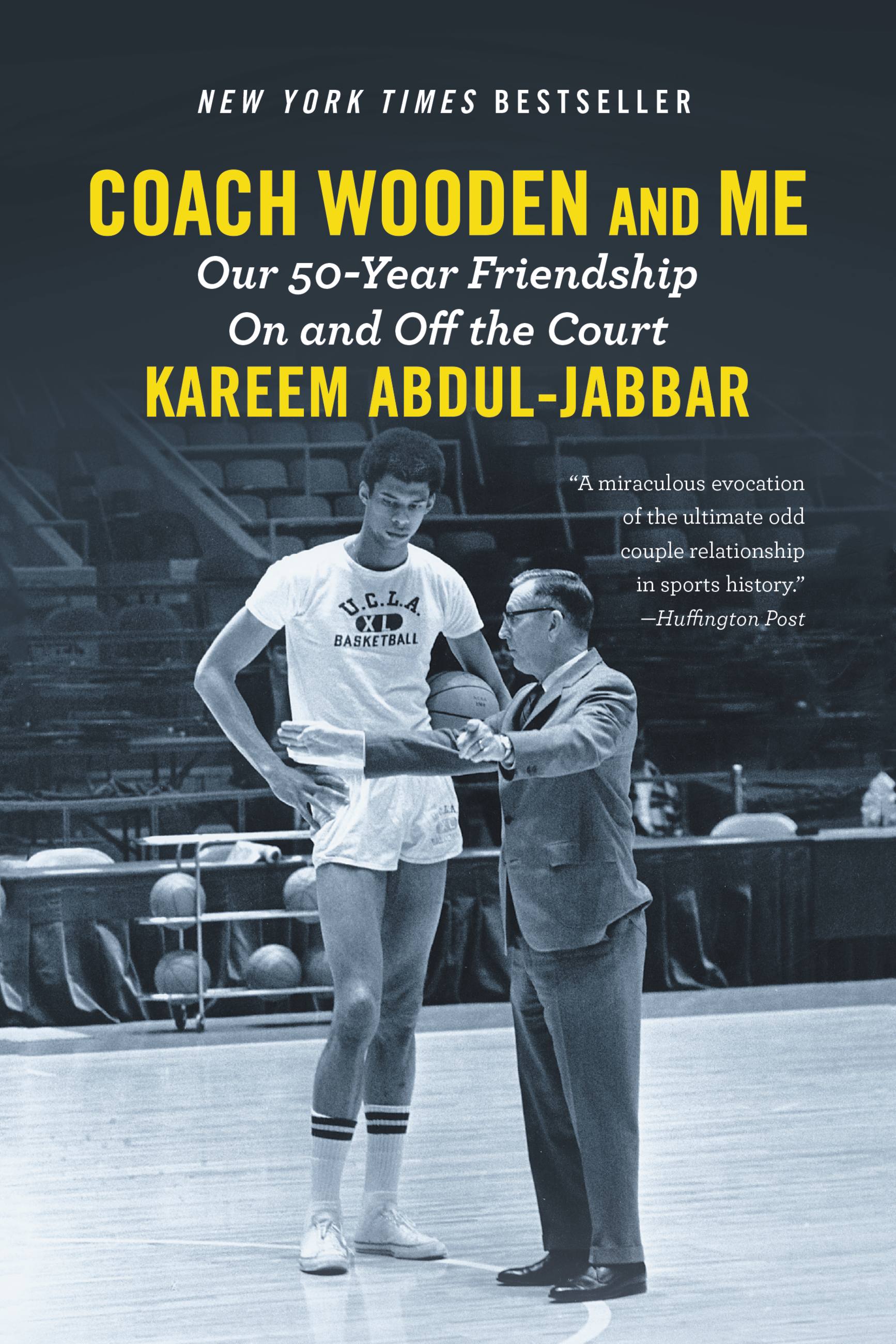

Coach Wooden and Me

Our 50-Year Friendship On and Off the Court

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 16, 2017

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781455542253

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Hardcover $37.00 $47.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 16, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Former NBA star and Presidential Medal of Freedom recipient Kareem Abdul-Jabbar explores his 50-year friendship with Coach John Wooden, one of the most enduring and meaningful relationships in sports history.

When future NBA legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was still an 18-year-old high school basketball prospect from New York City named Lew Alcindor, he accepted a scholarship from UCLA largely on the strength of Coach John Wooden’s reputation as a winner. It turned out to be the right choice, as Alcindor and his teammates won an unprecedented three NCAA championship titles. But it also marked the beginning of one of the most extraordinary and enduring friendships in the history of sports. In Coach Wooden and Me, Abdul-Jabbar reveals the inspirational story of how his bond with John Wooden evolved from a history-making coach-player mentorship into a deep and genuine friendship that transcended sports, shaped the course of both men’s lives, and lasted for half a century.

Coach Wooden and Me is a stirring tribute to the subtle but profound influence that Wooden had on Kareem as a player, and then as a person, as they began to share their cultural, religious, and family values while facing some of life’s biggest obstacles. From his first day of practice, when the players were taught the importance of putting on their athletic socks properly; to gradually absorbing the sublime wisdom of Coach Wooden’s now famous “Pyramid of Success”; to learning to cope with the ugly racism that confronted black athletes during the turbulent Civil Rights era as well as losing loved ones, Abdul-Jabbar fondly recalls how Coach Wooden’s fatherly guidance not only paved the way for his unmatched professional success but also made possible a lifetime of personal fulfillment.

Full of intimate, never-before-published details and delivered with the warmth and erudition of a grateful student who has learned his lessons well, Coach Wooden and Me is at once a celebration of the unique philosophical outlook of college basketball’s most storied coach and a moving testament to the all-conquering power of friendship.

Instant New York Times and USA Today Bestseller

President Barack Obama’s Favorite Book of 2017

A Boston Globe and Huffington Post Best Book of 2017 Pick

-

"This latest masterpiece by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is even better than all the rest... I'm captivated, enthralled, educated, and entertained as The King's words roll off the page even smoother than his skyhook did off his fingertips."Bill Walton

-

"A pleasant expression of deep appreciation for a man who changed the author's life by enriching it."Kirkus

-

"Anyone inclined to dismiss John Wooden and Abdul-Jabbar's relationship as merely coach and player... will rethink that miscalculation after reading this compact, engaging memoir."Publisher's Weekly

-

"Abdul-Jabbar and Wooden shared a priceless friendship, and this sensitive, sharply written account brings it to full, vivid life."Booklist (starred review)

-

"I always knew my Daddy felt this way about Kareem, but I never knew Kareem ever felt this way about my Dad."Nan Wooden, Coach Wooden's Daughter

-

"This stunning eulogy will appeal to readers far beyond the confines of sports. Highly recommended."Library Journal

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use