Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

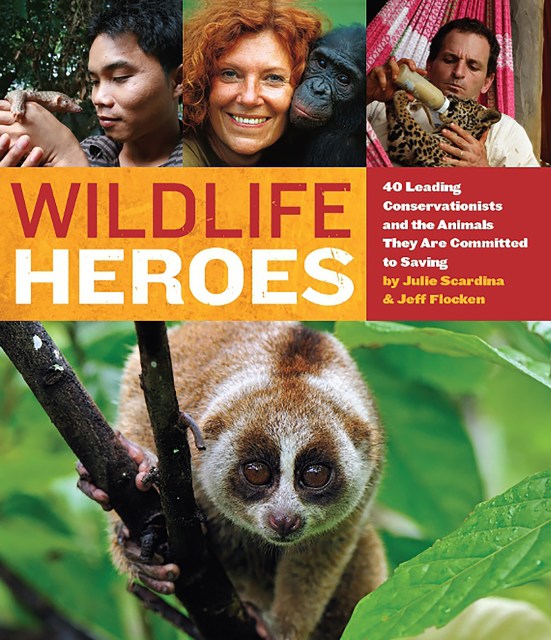

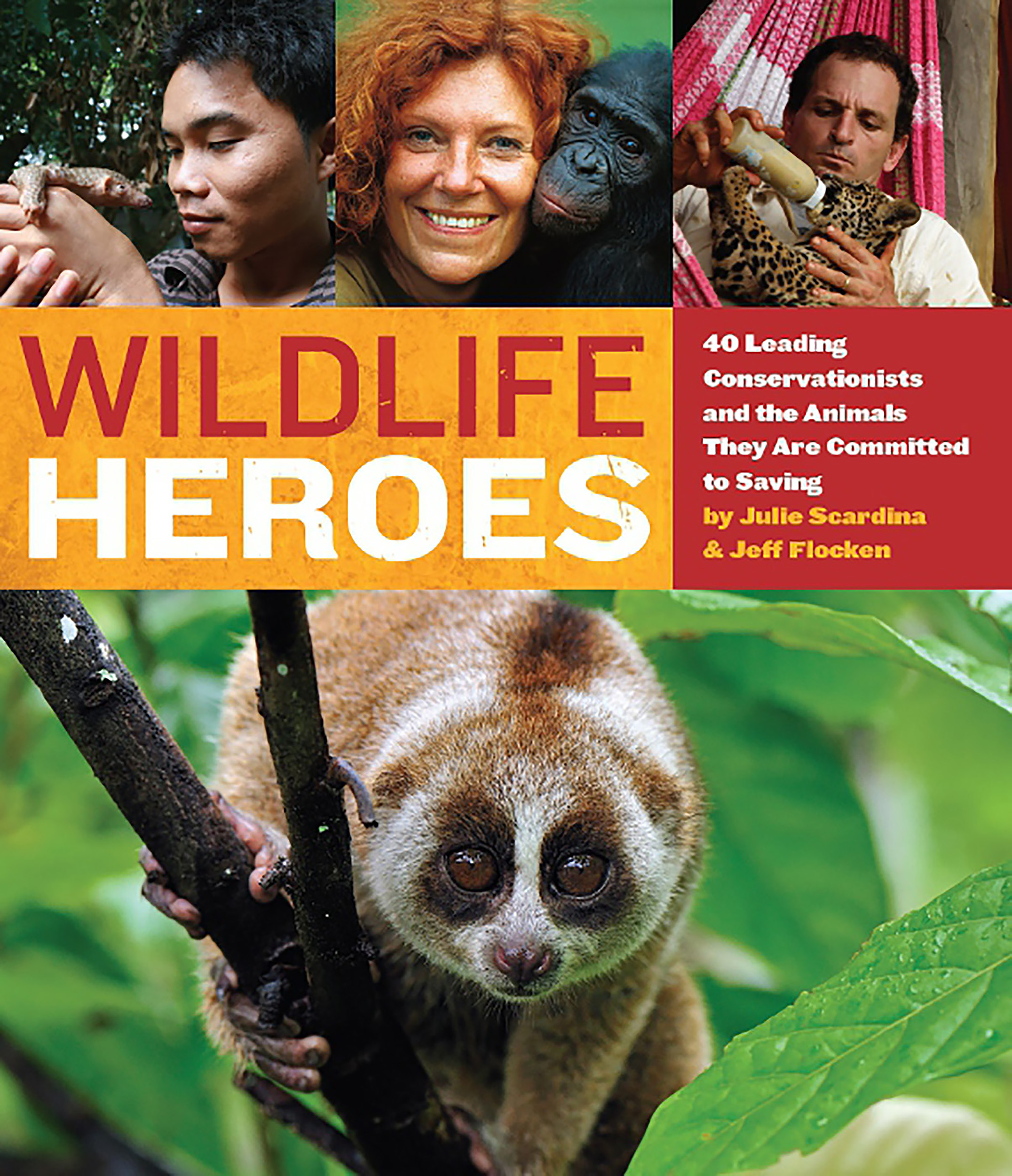

Wildlife Heroes

40 Leading Conservationists and the Animals They Are Committed to Saving

Contributors

By Jeff Flocken

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $12.99 $16.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 6, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

With one-third of known species being threatened with extinction, wildlife conservationists are some of the most important heroes on the planet, and Wildlife Heroes profiles the work of 40 of the leading conservationists and the animals and causes they are committed to saving, such as Belinda Low (zebras), Iain Douglas-Hamilton (elephants), Karen Eckert (sea turtles), S.T. Wong (sun bear), Steve Galster (wildlife trade), and Wangari Maathai (habitat loss). Since we all should have an interest in conservation, there is a chapter providing information on ways people can get involved and make a difference. Chapter introductions are by author Kuki Gallmann, actor Ted Danson, actress Stefanie Powers, Congressman Jay Inslee, and TV personality Jack Hanna.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 6, 2012

- Page Count

- 264 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762445165

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use