Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

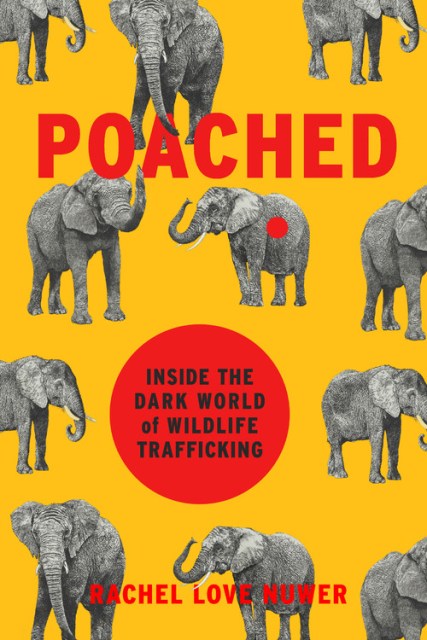

Poached

Inside the Dark World of Wildlife Trafficking

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$40.00Price

$50.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $40.00 $50.00 CAD

- ebook $17.99 $21.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 25, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Journalist Rachel Nuwer plunges the reader into the underground of global wildlife trafficking, a topic she has been investigating for nearly a decade. Our insatiable demand for animals — for jewelry, pets, medicine, meat, trophies, and fur — is driving a worldwide poaching epidemic, threatening the continued existence of countless species. Illegal wildlife trade now ranks among the largest contraband industries in the world, yet compared to drug, arms, or human trafficking, the wildlife crisis has received scant attention and support, leaving it up to passionate individuals fighting on the ground to try to ensure that elephants, tigers, rhinos, and more are still around for future generations.

As Reefer Madness (Schlosser) took us into the drug market, or Susan Orlean descended into the swampy obsessions of TheOrchid Thief, Nuwer–an award-winning science journalist with a background in ecology–takes readers on a narrative journey to the front lines of the trade: to killing fields in Africa, traditional medicine black markets in China, and wild meat restaurants in Vietnam. Through exhaustive first-hand reporting that took her to ten countries, Nuwer explores the forces currently driving demand for animals and their parts; the toll that demand is extracting on species across the planet; and the conservationists, rangers, and activists who believe it is not too late to stop the impending extinctions. More than a depressing list of statistics, Poached is the story of the people who believe this is a battle that can be won, that our animals are not beyond salvation.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 25, 2018

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306825507

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use