By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

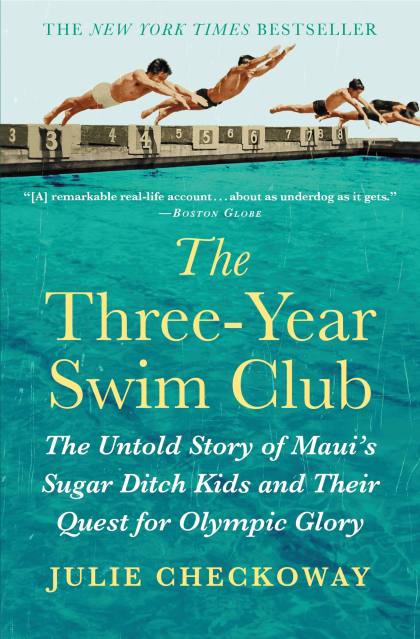

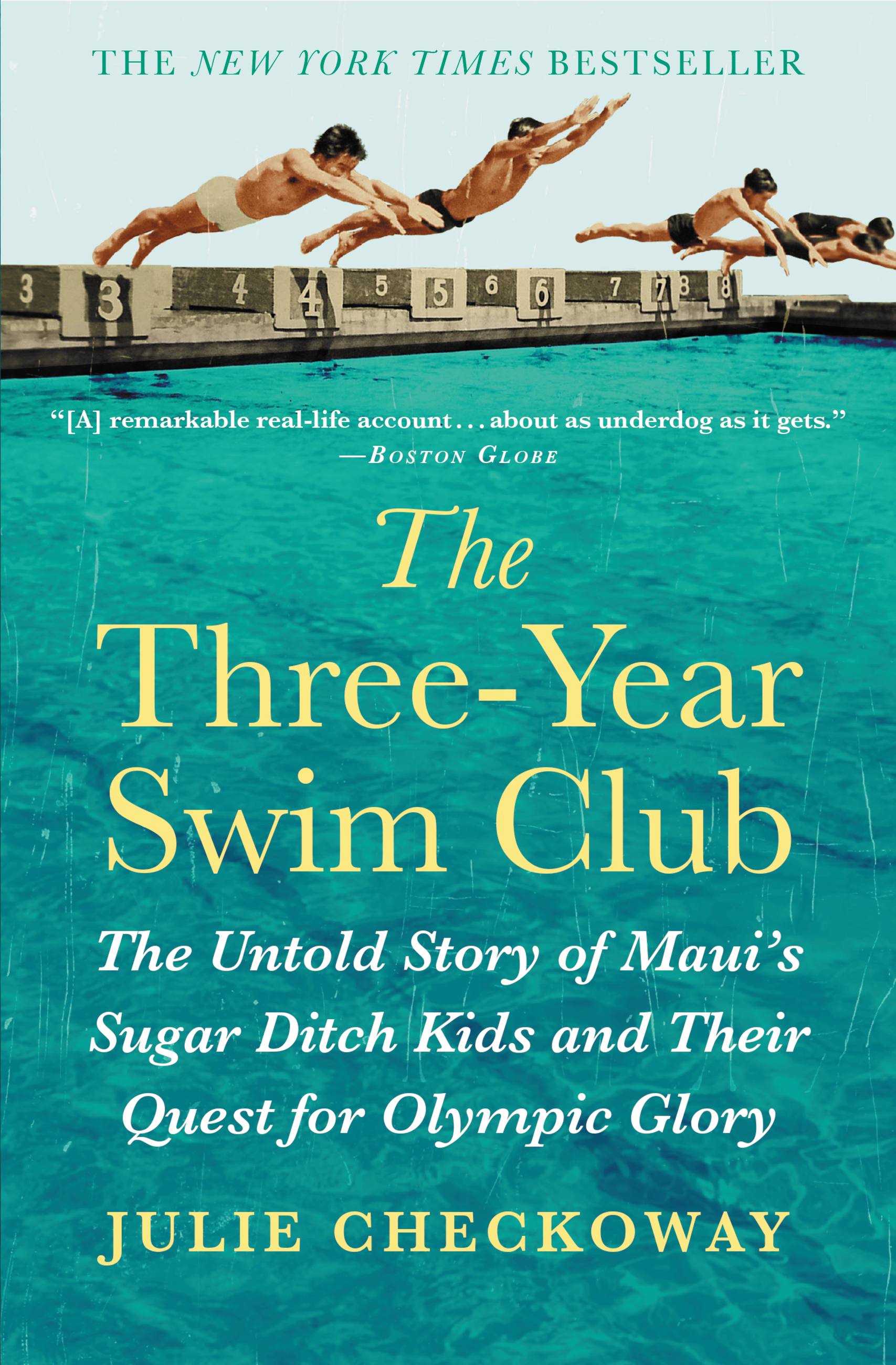

The Three-Year Swim Club

The Untold Story of Maui's Sugar Ditch Kids and Their Quest for Olympic Glory

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 27, 2015

- Page Count

- 448 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781455523436

Price

$11.99Price

$14.99 CADFormat

Format:

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 27, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In 1937, a schoolteacher on the island of Maui challenged a group of poverty-stricken sugar plantation kids to swim upstream against the current of their circumstance. The goal? To become Olympians.

They faced seemingly insurmountable obstacles. The children were Japanese-American and were malnourished and barefoot. They had no pool; they trained in the filthy irrigation ditches that snaked down from the mountains into the sugarcane fields. Their future was in those same fields, working alongside their parents in virtual slavery, known not by their names but by numbered tags that hung around their necks. Their teacher, Soichi Sakamoto, was an ordinary man whose swimming ability didn’t extend much beyond treading water.

In spite of everything, including the virulent anti-Japanese sentiment of the late 1930s, in their first year the children outraced Olympic athletes twice their size; in their second year, they were national and international champs, shattering American and world records and making headlines from L.A. to Nazi Germany. In their third year, they’d be declared the greatest swimmers in the world. But they’d also face their greatest obstacle: the dawning of a world war and the cancellation of the Games. Still, on the battlefield, they’d become the 20th century’s most celebrated heroes, and in 1948, they’d have one last chance for Olympic glory.

They were the Three-Year Swim Club. This is their story.

-

"A brightly told story of the triumph of underdogs... exuberant, well-researched...tense, vivid, and inspiring."Kirkus Reviews

-

"If the basis for the book doesn't sound amazing enough, how the story unfolds--Japan vying for the Olympic games, Pearl Harbor being bombed, WWII changing the world forever--allows the story and characters to evolve in uplifting and heartbreaking ways...it is evident that Checkoway's ability to set a scene is uncanny and accomplished...Depicting determination, discrimination, hope, anguish, hard work, and hard choices, Checkoway has created a sports history that is singular in its own right, and a fitting testament to the over 200 youths who swam for many reasons toward one goal: 'Olympics First! Olympics Always.'"Publishers Weekly (starred review)

-

"Remarkable real-life account...about as underdog as it gets."Boston Globe

-

"An inspiring true tale of grit and determination... Checkoway skillfully weaves vivid scenes into a larger narrative with a varied cast of characters to create a stirring, though exhaustive, account ...Pair this with The Boys in the Boat."Booklist

-

"This story of one (at first) seemingly unremarkable man and his effect on camp children and the world of swimming is both inconceivable and dazzling. You won't want to miss it."Book Reporter

-

"This captivating nonfiction, featuring engaging individuals and portraying a tumultuous time in history, chronicles Hawaii's second golden age of swimming. Sports and history enthusiasts will enjoy this title as much as book clubs and general readers."Library Journal

-

"Checkoway carefully weaves together facts into a sweeping historical tapestry."The Salt Lake Tribune

-

"Checkoway's story of youthful perseverance will earn a place on the shelf with The Boys in the Boat."The National Book Review

-

"Save the story she has, through exhaustive research and sparkling prose."BookPage

-

"[A] reverent tale...Through meticulous research, Checkoway brings crisp focus to a fuzzy time in American history...The book carries hints of The Boys in the Boat...Checkoway stays true to her salvage mission. She unearths characters flawed and fetching and shines an unflinching light on race and class...glorious storytelling and a triumphant, unpredictable finish."Minneapolis Star Tribune

-

"Shows that sometimes all you need to start something epic is a dream."Bustle

-

"Checkoway takes on an incredible story of overcoming obstacles and defying the odds...poignant."Swimming World Magazine

-

"This story of one (at first) seemingly unremarkable man and his effect on camp children and the world of swimming is both inconceivable and dazzling. You won't want to miss it."Book Reporter

-

"A good and graceful writer."Honolulu Magazine

-

"A made-for-the-screen story."Outside Magazine

-

"Exceptionally well-researched and well-written."ESPN.com

-

"A wild, improbable story that makes for popular Hollywood movies but rarely happens in real life. But this story's real."Maui Time

-

"This true story is entertaining and absorbing and good for the soul."Sunset Magazine

-

"A classic underdog story...Had [Checkoway] not written this book, their exact story might have never been told, but instead, American swimming's most fascinating chapter gets the shine it deserves."Deadspin

-

"Lively, at times history reading more dramatic than fiction...surprises wait in both the pool and in the story of these remarkable characters."Petoskey News

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use