Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

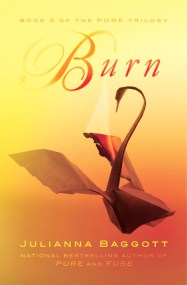

Pure

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 4, 2012

- Page Count

- 480 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781455503056

Price

$24.99Price

$31.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $11.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 4, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

We know you are here, our brothers and sisters . . .

Pressia barely remembers the Detonations or much about life during the Before. In her sleeping cabinet behind the rubble of an old barbershop where she lives with her grandfather, she thinks about what is lost-how the world went from amusement parks, movie theaters, birthday parties, fathers and mothers . . . to ash and dust, scars, permanent burns, and fused, damaged bodies. And now, at an age when everyone is required to turn themselves over to the militia to either be trained as a soldier or, if they are too damaged and weak, to be used as live targets, Pressia can no longer pretend to be small. Pressia is on the run.

Burn a Pure and Breathe the Ash . . .

There are those who escaped the apocalypse unmarked. Pures. They are tucked safely inside the Dome that protects their healthy, superior bodies. Yet Partridge, whose father is one of the most influential men in the Dome, feels isolated and lonely. Different. He thinks about loss-maybe just because his family is broken; his father is emotionally distant; his brother killed himself; and his mother never made it inside their shelter. Or maybe it’s his claustrophobia: his feeling that this Dome has become a swaddling of intensely rigid order. So when a slipped phrase suggests his mother might still be alive, Partridge risks his life to leave the Dome to find her.

When Pressia meets Partridge, their worlds shatter all over again.

Series:

-

"What lifts PURE from the glut of blood-spattered young adult fiction is not the story Baggott tells but the exquisite precision of her prose...discomfiting and unforgettable."The New York Times Sunday Book Review

-

"Baggott's highly anticipated postapocalyptic horror novel...is a fascinating mix of stark, oppressive authoritarianism and grotesque anarchy...Baggott mixes brutality, occasional wry humor, and strong dialogue into an exemplar of the subgenre."Publisher's Weekly (STARRED review)

-

"A great gorgeous whirlwind of a novel, boundless in its imagination. You will be swept away."Justin Cronin, New York Times bestselling author of The Passage

-

"A boiling and roiling glorious mosh-pit of a book, full of wonderful weirdness, tenderness, and wild suspense. If Katniss could jump out of her own book and pick a great friend, I think she'd find an excellent candidate in Pressia."Aimee Bender, author of The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake

-

"PURE is a dark adventure that is both startling and addictive at once. Pressia Belze is one part manga heroine and one part post-apocalyptic Alice, stranded in a surreal Wonderland where everyone and everything resonates with what has been lost. Breathtaking and frightening. I couldn't stop reading PURE."Danielle Trussoni, bestselling author of Angelology

-

"PURE is a dark adventure that is both startling and addictive at once. Pressia Belze is one part manga heroine and one part post-apocalyptic Alice...Breathtaking and frightening. I couldn't stop reading PURE."Danielle Trussoni, bestselling author of Angelology

-

"PUREis not just the most extraordinary coming-of-age novel I've ever read, it is also a beautiful and savage metaphorical assessment of how all of us live in this present age. This is an important book."Robert Olen Butler, Pulitzer Prize winner and author of A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain

-

It's nearly impossible to stop reading as Baggott delves fearlessly into a grotesque and fascinating future populated by strangely endearing victims (and perpetrators) of a wholly unique apocalypse. And trust me, PURE packs one hell of an apocalypse."Daniel H. Wilson, New York Times bestselling author of Robopocalypse

-

"From the first page on, there are no brakes on this book. It's nearly impossible to stop reading as Baggott delves fearlessly into a grotesque and fascinating future populated by strangely endearing victims (and perpetrators) of a wholly unique apocalypse. And trust me, PURE packs one hell of an apocalypse."Daniel H. Wilson, New York Times bestselling author of Robopocalypse

-

"A boiling and roiling glorious mosh-pit of a book, full of wonderful weirdness, tenderness, and wild suspense. If Katniss could jump out of her own book and pick a great friend, I think she'd find an excellent candidate in Pressia."Aimee Bender, author of The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake