By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

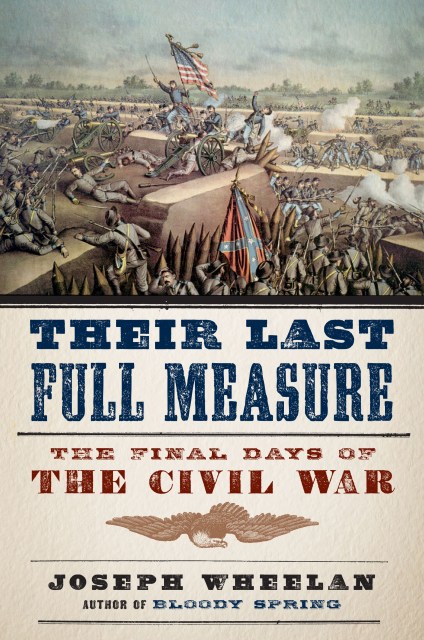

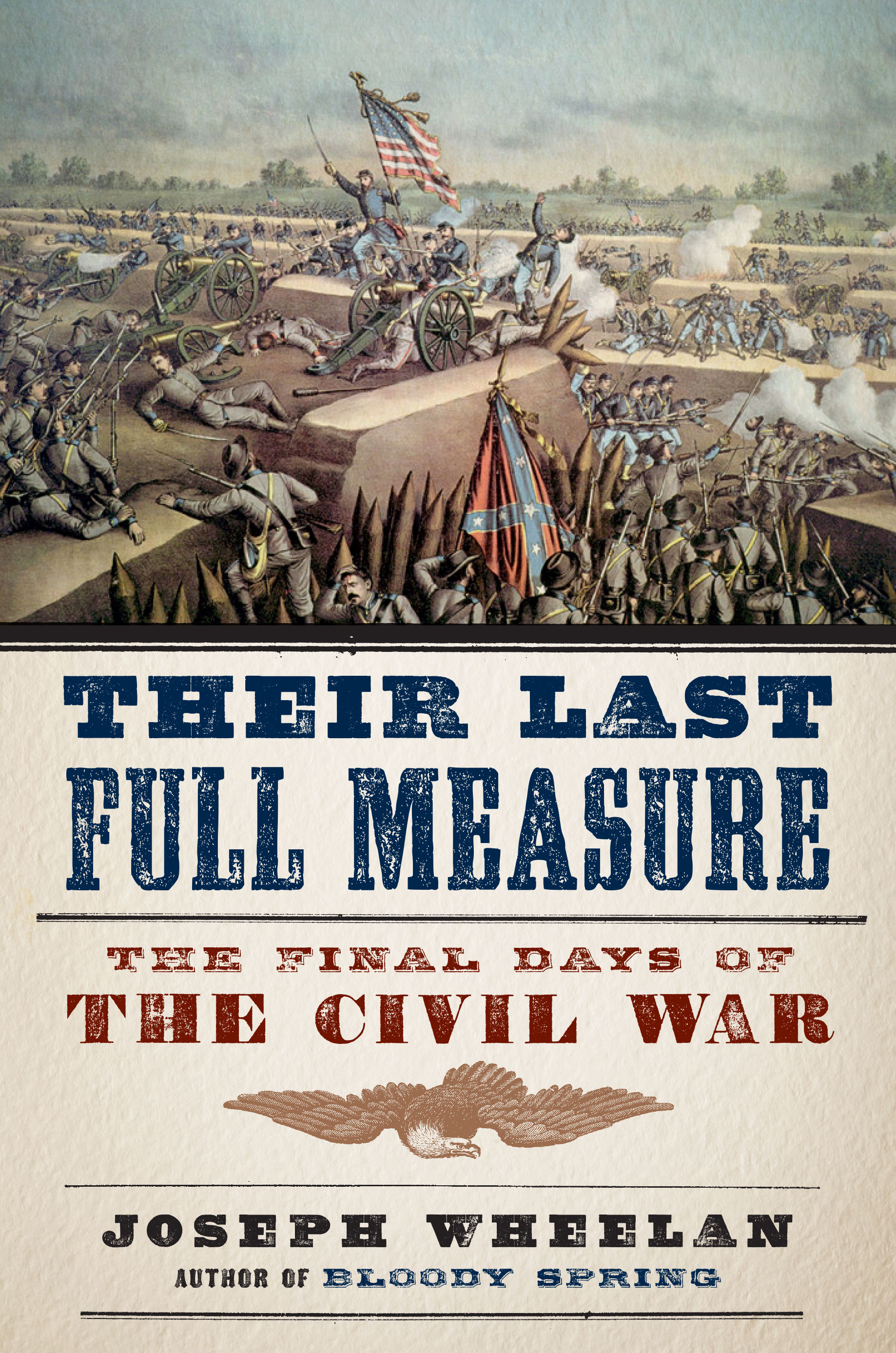

Their Last Full Measure

The Final Days of the Civil War

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 24, 2015

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780306823619

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 24, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

As the Confederacy crumbled under the Union army’s relentless “hammering,” Federal armies marched on the Rebels’ remaining bastions in Alabama, the Carolinas, and Virginia. General William T. Sherman’s battle-hardened army conducted a punitive campaign against the seat of the Rebellion, South Carolina, while General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant sought to break the months-long siege at Petersburg, defended by Robert E. Lee’s starving Army of Northern Virginia.

In Richmond, Confederate President Jefferson Davis struggled to hold together his unraveling nation while simultaneously sanctioning diplomatic overtures to bid for peace. Meanwhile, President Abraham Lincoln took steps to end slavery in the United States forever.

Their Last Full Measure relates these thrilling events, which followed one on the heels of another, from the battles ending the Petersburg siege and forcing Lee’s surrender at Appomattox to the destruction of South Carolina’s capital, the assassination of Lincoln, and the intensive manhunt for his killer. The fast-paced narrative braids the disparate events into a compelling account that includes powerful armies; leaders civil and military, flawed and splendid; and ordinary people, black and white, struggling to survive in the war’s wreckage.

-

Praise for Their Last Full Measure

William C. Davis, award-winning author of Crucible of Command

"It may have been apparent to many by January 1865 that the war between Union and Confederacy was winding down to an inevitable denouement, but to the men in the armies and the exhausted citizens at home, the New Year promised only new trauma on new battlefields. Joseph Wheelan's Their Last Full Measure ably re-creates those feelings of dread and anticipation, and growing inevitability, in portraits and words of the men and women who lived those final months. His descriptions of the horrors of combat on the field, and the often-hidden battles among the presidents, cabinets, and congresses, are dramatically portrayed in a narrative that never loses pace or interest."

Kirkus Reviews, April 2015

“First-rate study of the often overlooked closing months of the Civil War…The author capably traces the closing military campaign in Virginia…At the same time, he writes critically, by way of foreshadowing, of the failure of Reconstruction...Particularly interesting are Wheelan's occasional forays into speculation: what might have happened…Wheelan has combed entire libraries to make this thoroughly readable, lucid survey. Well-practiced buffs will welcome the book, but novices can approach it without much background knowledge, too.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use