By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

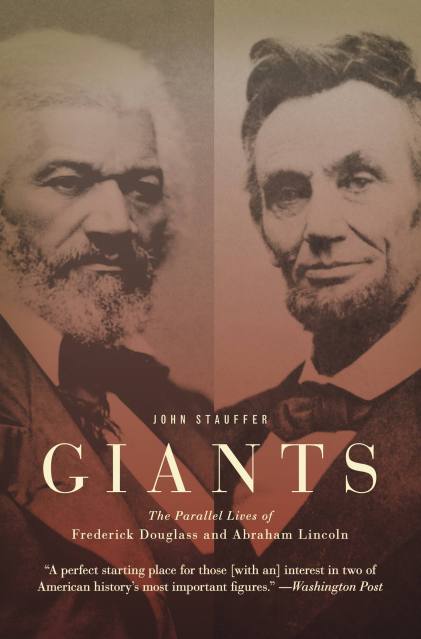

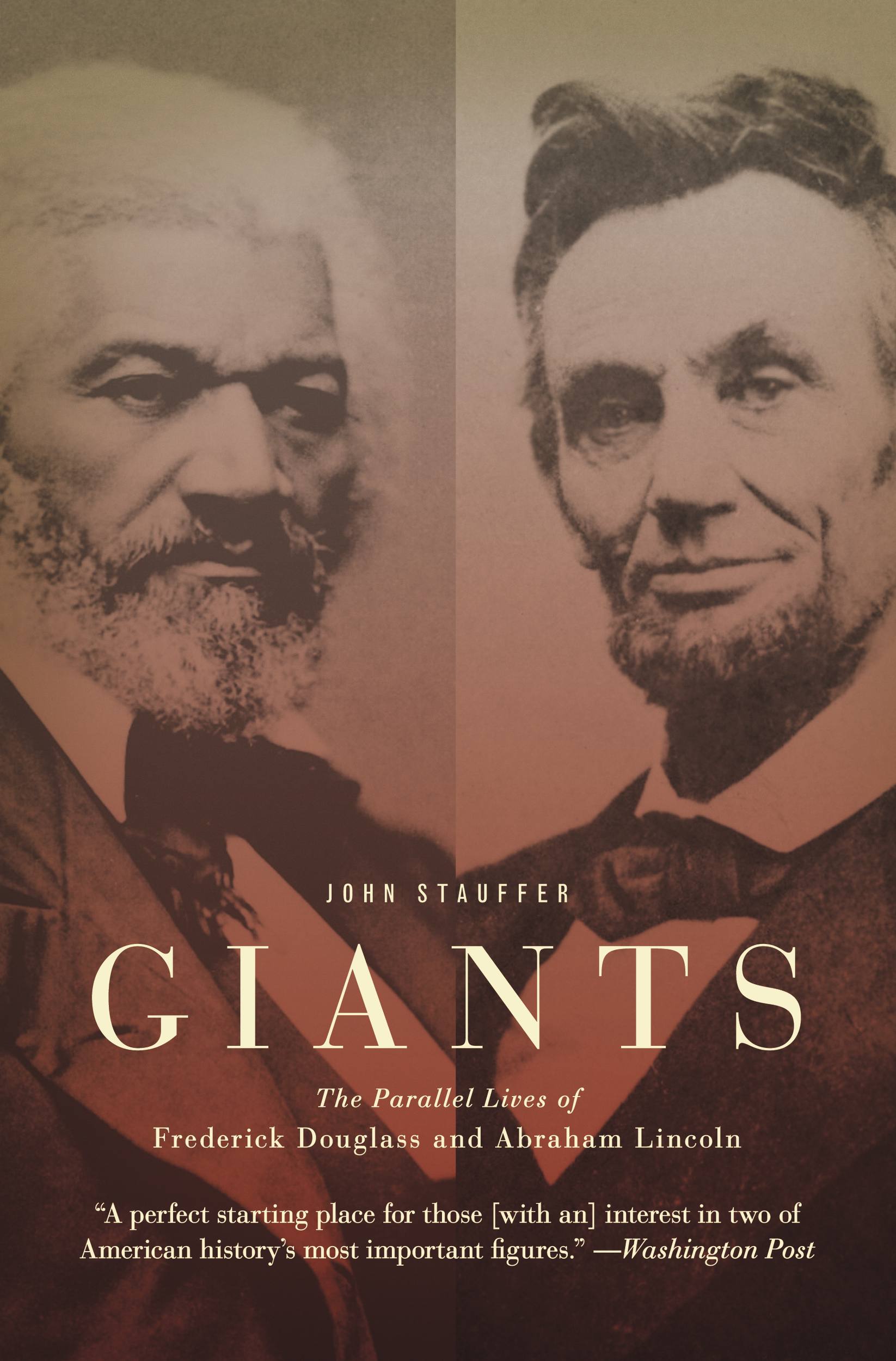

Giants

The Parallel Lives of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 3, 2008

- Page Count

- 448 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9780446543002

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 3, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Lincoln was born dirt poor, had less than one year of formal schooling, and became the nation’s greatest president. Douglass spent the first twenty years of his life as a slave, had no formal schooling-in fact, his masters forbade him to read or write-and became one of the nation’s greatest writers and activists, as well as a spellbinding orator and messenger of audacious hope, the pioneer who blazed the path traveled by future African-American leaders.

At a time when most whites would not let a black man cross their threshold, Lincoln invited Douglass into the White House. Lincoln recognized that he needed Douglass to help him destroy the Confederacy and preserve the Union; Douglass realized that Lincoln’s shrewd sense of public opinion would serve his own goal of freeing the nation’s blacks. Their relationship shifted in response to the country’s debate over slavery, abolition, and emancipation.

Both were ambitious men. They had great faith in the moral and technological progress of their nation. And they were not always consistent in their views. John Stauffer describes their personal and political struggles with a keen understanding of the dilemmas Douglass and Lincoln confronted and the social context in which they occurred. What emerges is a brilliant portrait of how two of America’s greatest leaders lived.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use