Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

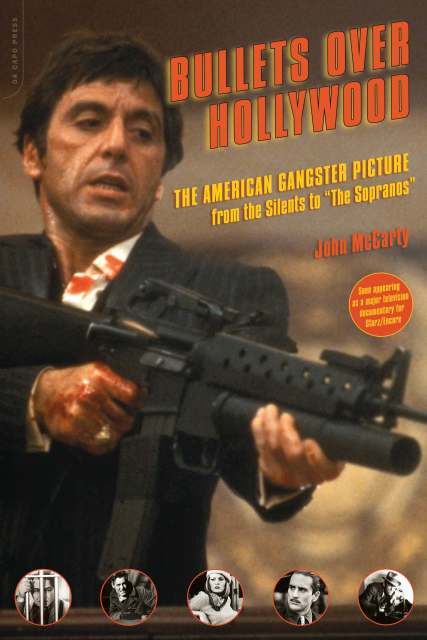

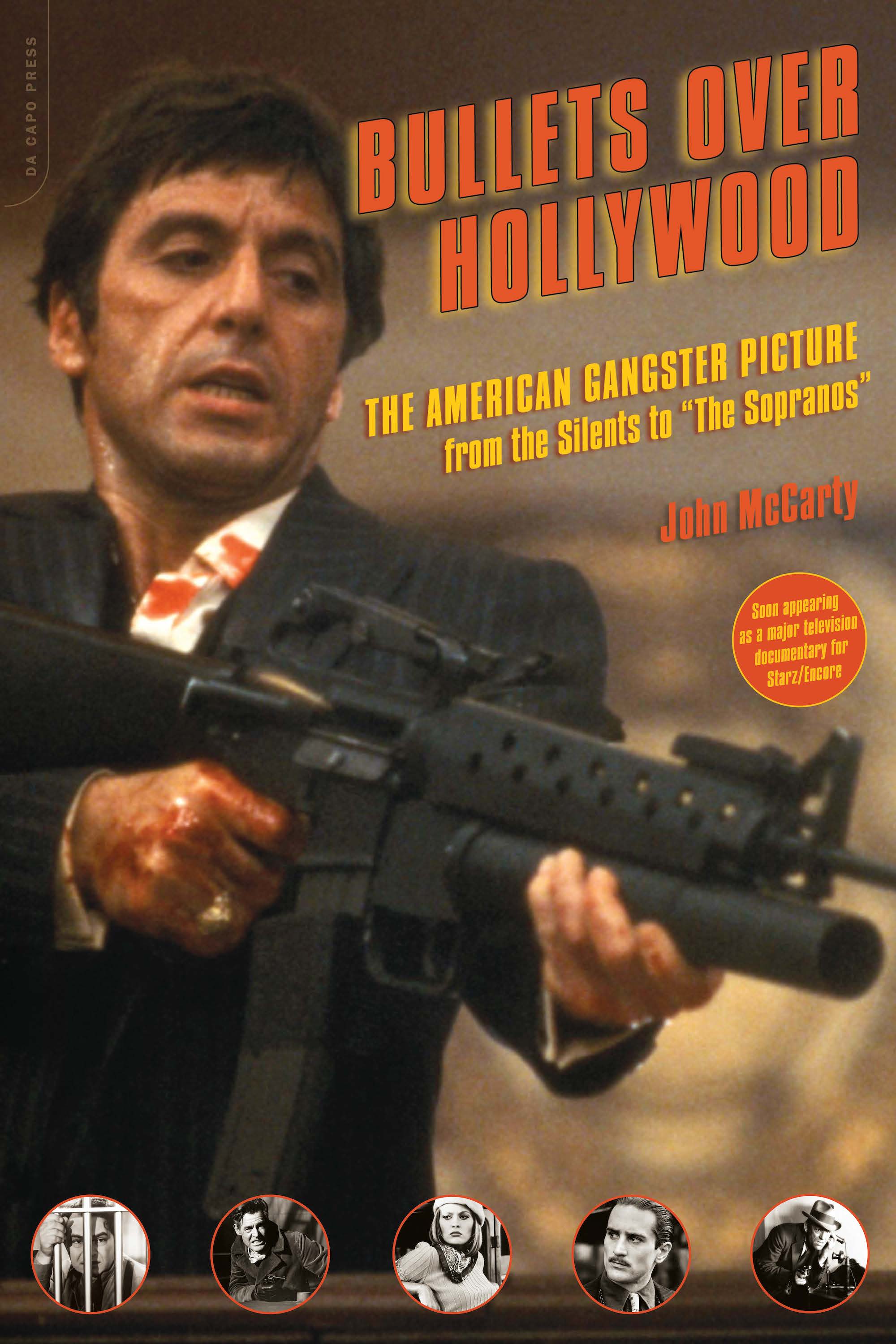

Bullets Over Hollywood

The American Gangster Picture From The Silents To "The Sopranos"

Contributors

By John McCarty

Formats and Prices

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 27, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The gangster, like the gunslinger, is a classic American character-and the gangster movie, like the Western, is one of the American cinema’s enduring film genres. From Scarface to White Heat, from The Godfather to The Usual Suspects, from Once Upon a Time in America to Road to Perdition, gangland on the screen remains as popular as ever.In Bullets over Hollywood, film scholar John McCarty traces the history of mob flicks and reveals why the films are so beloved by Americans. As McCarty demonstrates, the themes, characters, landscapes, stories-the overall iconography-of the gangster genre have proven resilient enough to be updated, reshaped, and expanded upon to connect with even today’s young audiences. Packed with fascinating behind-the-scenes anecdotes and information about real-life hoods and their cinematic alter egos, insightful analysis, and a solid historical perspective, Bullets over Hollywood will be the definitive book on the gangster movie for years to come.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 27, 2009

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780786738755

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use