By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

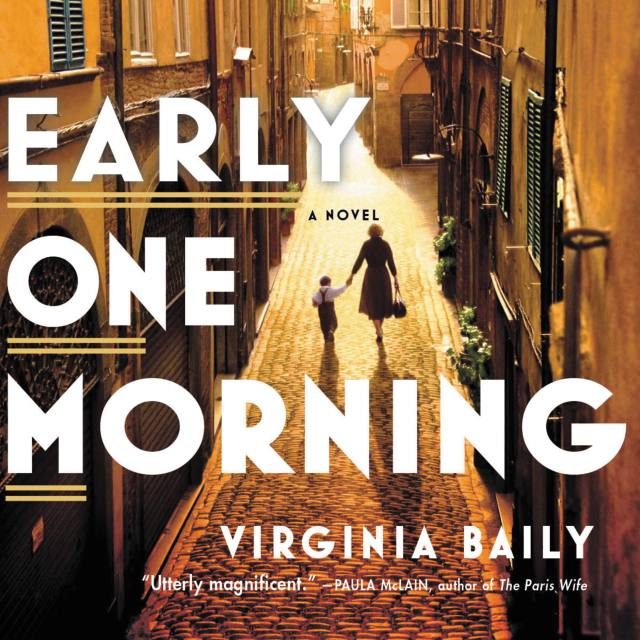

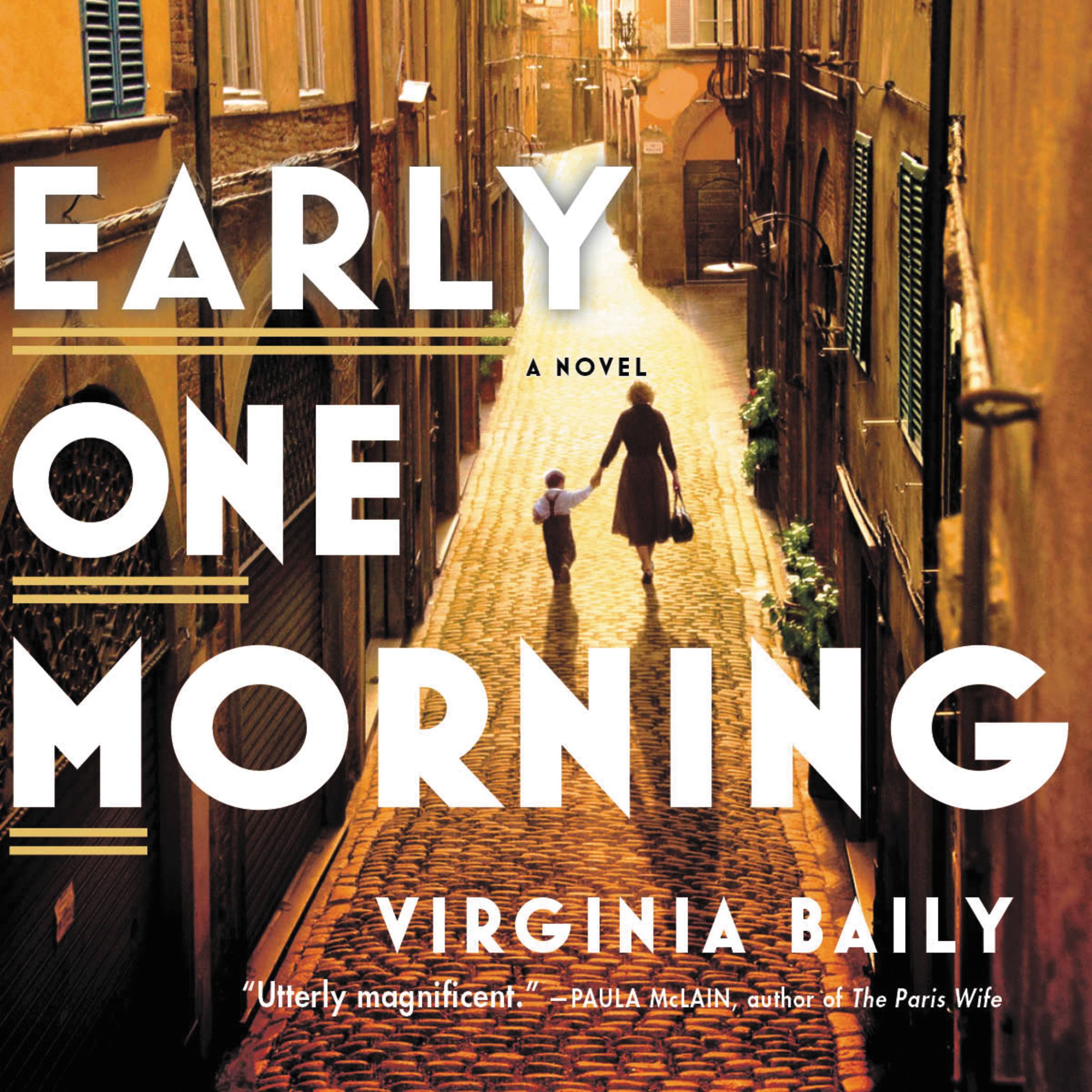

Early One Morning

Contributors

Read by Jilly Bond

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 29, 2015

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781478904809

Price

$27.99Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

- ebook $13.99 $16.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $32.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 29, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Chiara Ravello is about to flee occupied Rome when she locks eyes with a woman being herded on to a truck with her family. Claiming the woman’s son, Daniele, as her own nephew, Chiara demands his return; only as the trucks depart does she realize what she has done. She is twenty-seven, with a sister who needs her constant care, a hazardous journey ahead, and now a child in her charge.

Several decades later, Chiara lives alone in Rome, a self-contained woman working as a translator. Always in the background is the shadow of Daniele, whose absence and the havoc he wrought on Chiara’s world haunt her. Then she receives a phone call from a teenager claiming to be his daughter, and Chiara knows it is time to face up to the past.

Genre:

-

"From the broken Jewish ghetto and dusky countryside of occupied Italy during WWII to the bustling Trastevere cafes of Rome in the 1970s, Virginia Baily offers an affecting contemplation of the past, personal identity, and the complexity and diversity of human bonds. Early One Morning is the sort of book you can't put down and then stays with you, like the best of journeys, long after it's finished."Anne Korkeakivi, author of An Unexpected Guest

-

"Early One Morning heralds the arrival of an exciting new voice in fiction, with a story that is instantly engaging, and characters that effortlessly lift from the page and are rendered so rich and full that they wrap themselves around you and refuse to let go. Beautifully written and emotionally taut, Virginia Baily's Early One Morning is a powerhouse of a debut."Jason Hewitt, author of The Dynamite Room

-

"Early One Morning isn't just an incandescent novel, but the rarest of reading experiences, offering a view both wrenching and luminous of how love pushes us past what we're capable of, and somehow-impossibly-reclaims us when we're long past saving. Utterly magnificent."Paula McLain, author of The Paris Wife

-

"Wonderful.... I was completely inside it from the first pages, just that delicious (rare) feeling of knowing you're in safe hands, this writer isn't going to make a mess of anything, or forfeit your trust or your belief. It managed to be so witty and dry and true.... Vividly intelligent, gripping and moving and alive."Tessa Hadley, author of Clever Girl

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use