Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

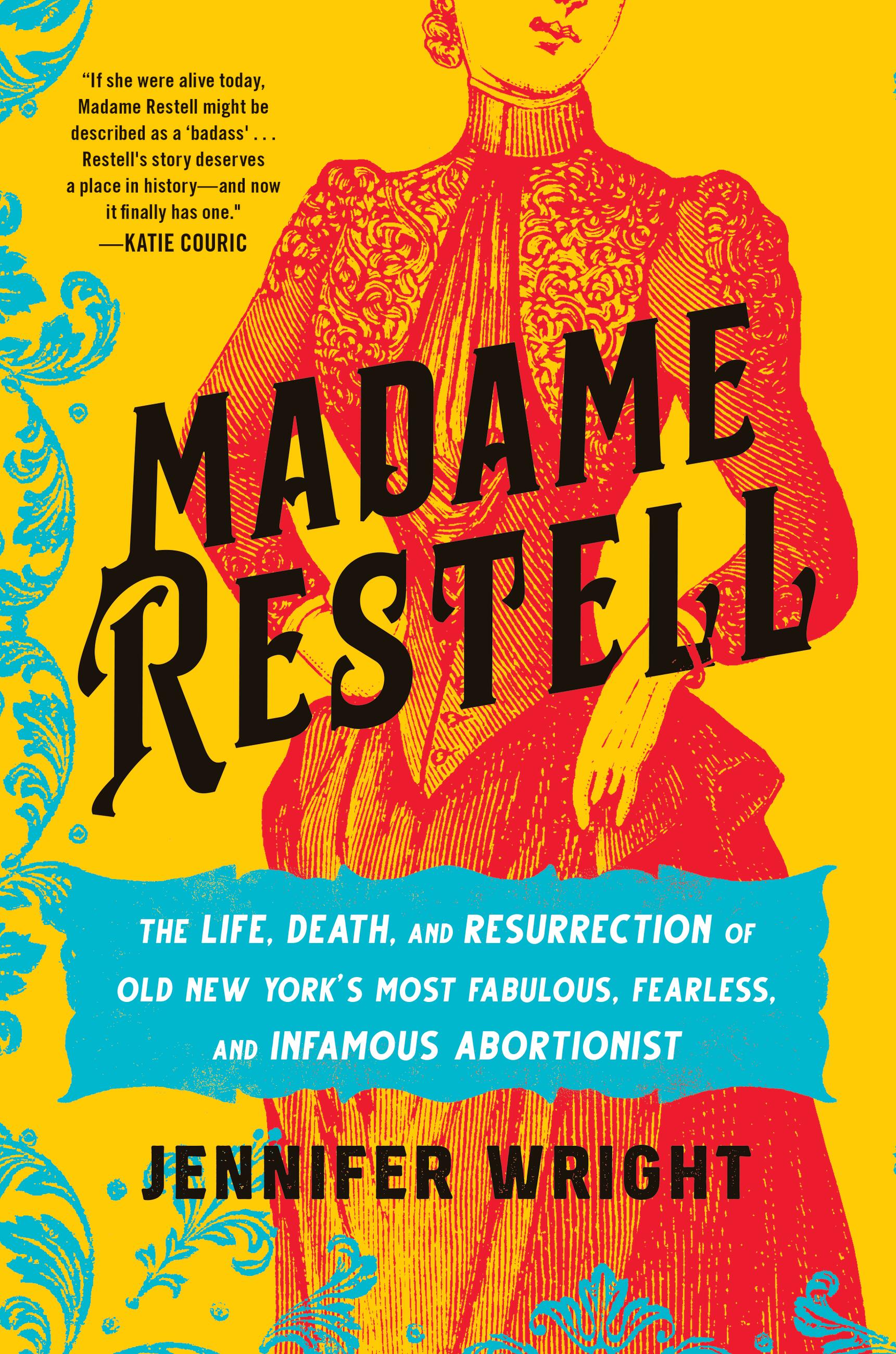

Madame Restell

The Life, Death, and Resurrection of Old New York's Most Fabulous, Fearless, and Infamous Abortionist

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 28, 2023

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780306826825

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 28, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

An industrious immigrant who built her business from the ground up, Madame Restell was a self-taught surgeon on the cutting edge of healthcare in pre-Gilded Age New York, and her bustling “boarding house” provided birth control, abortions, and medical assistance to thousands of women—rich and poor alike. As her practice expanded, her notoriety swelled, and Restell established her-self as a prime target for tabloids, threats, and lawsuits galore. But far from fading into the background, she defiantly flaunted her wealth, parading across the city in designer clothes, expensive jewelry, and bejeweled carriages, rubbing her success in the faces of the many politicians, publishers, fellow physicians, and religious figures determined to bring her down.

Unfortunately for Madame Restell, her rise to the top of her field coincided with “the greatest scam you’ve never heard about”—the campaign to curtail women’s power by restricting their access to both healthcare and careers of their own. Powerful, secular men—threatened by women’s burgeoning independence—were eager to declare abortion sinful, a position endorsed by newly-minted male MDs who longed to edge out their feminine competition and turn medicine into a standardized, male-only practice. By unraveling the misogynistic and misleading lies that put women’s lives in jeopardy, Wright simultaneously restores Restell to her rightful place in history and obliterates the faulty reasoning underlying the very foundation of what has since been dubbed the “pro-life” movement.

Thought-provoking, character-driven, boldly written, and feminist as hell, Madame Restell is required reading for anyone and everyone who believes that when it comes to women’s rights, women’s bodies, and women’s history, women should have the last word.

-

**Longlisted for the Brooklyn Public Library Book Prize in Nonfiction (2023)**

**Smithsonian Magazine, “10 Best History Books of 2023”**

**Audible, "12 Best History Listens of 2023" ****An Amazon EDITOR'S PICK for BEST BOOKS OF 2023 SO FAR in BIOGRAPHY/MEMOIR and HISTORY**

**An Amazon EDITOR'S PICK for BEST BOOKS OF THE MONTH (March 2023)**

**INDIE NEXT List Pick for March 2023**

**A Bookshop.Org EDITOR'S PICK (March 2023)***

Next Idea Book Club, "February Must Reads" and "40 Nonfiction Books to Watch Out For in 2023"

Cosmopolitan, "11 Best Books to Put on Your TBR"

Amazon, Best Books in History and Nonfiction (March 2023)

The Spectator, "Books to Watch Out For in 2023"

American Journal of Bioethics, "Recommended Reading" -

"Painfully timely... Wright observes that Americans don’t take well to learning history. When it is delivered with this kind of blunt force, however, perhaps they might. Whatever readers end up thinking of Madame Restell, they surely cannot miss the core lesson: that there has never been a culture in human history without abortion. The only variable has ever been the cost.New York Times Book Review

-

“A searing portrait of an indomitable woman… Wright juxtaposes her subject’s story with those of Restell’s patients and an overview of the broader conversation surrounding abortion in the late 19th century.”Smithsonian Magazine

-

"Wright’s book dances off the page."Washington Post

-

"They say that history is written by the victors, which goes a long way towards explaining the anonymity of Ann Trow, a.k.a. Madame Restell. Jennifer Wright’s meticulously researched, dryly humorous, and frankly feminist biography of the glamorous, celebrated, and unapologetic abortionist—whose defiance in the face of an oppressive patriarchy can best be described as (ahem) ballsy—should set that right... Dismantling centuries-old misconceptions, Wright blends rousing biography and eye-opening medical and cultural history lessons in this compulsively readable biography of a remarkable woman."Amazon

-

"Madame Restell is a timely portrait of one woman’s boldness mixes deep research with page-turning prose to bring Madame Restell’s times to life, reminding what’s at stake in the fight for bodily autonomy." (Editor's Pick)Bookshop.Org

-

“By unraveling the misogynistic and misleading lies that put women’s lives in jeopardy, Wright simultaneously restores Restell to her rightful place in history and obliterates the faulty reasoning underlying the very foundation of what has since been dubbed the 'pro-life' movement.”Daily Kos

-

"Restell is central to the story of the dismantling of American women's reproductive freedom during the last half of the nineteenth century, yet she has largely been treated as a curiosity and a footnote.... [This work] fill[s] a grievous void... Wright... has produced an engaging... chronicle, with clear passion..."New York Review of Books

-

“This brightly written biography of a fierce woman lost to history will appeal strongly to feminists.”New York Journal of Books

-

"A compelling study."Los Angeles Review of Books

-

“This captivating portrait of the infamous self-taught surgeon and medical celebrity is also a glance at shifting mid-19th century mores, male power players, and their strategic campaign to curtail female independence and criminalize abortion.”Globe & Mail

-

“Wright has vividly and thoroughly revived the dark story of Madame Restell, an undeniably powerful entrepreneur who rose from seemingly hopeless poverty by exercising her innate abilities, excelling and enjoying the fruits of her labors. She examines the thorny issue of abortion from numerous angles, treating it deftly. Restell’s life story encompasses subject matter that has much to teach, and Wright provides diligent, thoughtful research to make that possible.”BookReporter.com

-

“This is a book that’ll make you want to stand up and say, ‘HECK YES!’”"Book Worm Says" column

-

"The fact that Ann Trow isn’t a well-known feminist heroine is a travesty. Thankfully, Jennifer Wright is here with an extensively researched, compulsively readable account of this singularly fascinating woman and her extraordinary legacy that still affects so much of the country even today... Lost to history by the concerted efforts of power-hungry, sexist men, this remarkable woman is finally receiving her due in this fast-paced, whirlwind of a book. This book is more than a retrospective on the life of a forgotten heroine; it’s a telling account of how women’s health became both a commodity and a tool of oppression. Highly recommended for anyone with an eye on today’s politics and wonders how we got here."CityView

-

“Wright’s well-researched biography is not only interesting, but, sadly, timely. A fresh contribution to women’s history.”Kirkus

-

"[An] impassioned and irreverent biography... Wright paints a vivid picture of Restell’s rise to prominence and weaves in intriguing details about the history of birth control and abortion. This feminist history fascinates."Publishers Weekly

-

"Always entertaining."London Review of Books

-

“Jennifer Wright is one of the best writers of history working today, and it’s a gift to all of us that she’s choosing to focus her tremendous skill as a researcher and singular voice on an all-but-forgotten figure like Madame Restell. To call this book timely would be an understatement. It functions not only as a brilliant biography but also a timeless reminder of the way history can be erased and changed to serve modern political purposes.”DANA SCHWARTZ, #1 New York Times bestselling author of ANATOMY: A LOVE STORY and host of NOBLE BLOOD

-

“It may be a 19th century story, but Madame Restell's battles with sanctimonious hypocrites and condescending men feels all too modern, especially in an era when basic rights are once again being taken away. Luckily, Jennifer Wright has a wry humor and light hand, making this book as fun as it is inspiring.”AMANDA MARCOTTE, Senior Political Writer at Salon and Author of TROLL NATION

-

“Reading Jennifer Wright’s books is always like having a brilliant friend tell you fascinating history you can’t believe you never heard of before. MADAME RESTELL is no exception—it’s a page-turning ride through the Gilded Age that will make you laugh, make you cry, and enrage you by turns.”ALEXANDRA PETRI, Washington Post columnist and author of Alexandra Petri’s US History

-

“Like the woman herself, MADAME RESTELL is smart, fascinating, complicated, and not to be denied. Wright has written that most delicious of books, the true story of a bad bitch, a woman whose work is as relevant as your social media timeline, only it’s true.”QUINN CUMMINGS, author of NOTES FROM THE UNDERWIRE and SMALL STORIES (2018-2020)

-

“MADAME RESTELL is a book about one of America's most infamous 19th century abortion providers, which is to say it's a delightful, indecorous, and sometimes disturbing story about the whole of American history: Capitalism and class, feminism and freedom, and puritanical hypocrites who find their authority challenged by women who want a littler power (and are willing to be more than a little bawdy in order to get it). If you want to understand contemporary politics, from brave women who break the law to the misogynist moral scolds who still want women under their thumb to the inevitable interplay of despair and resistance in the pursuit of liberation—or if you just want to read a truly captivating tale of the most important woman you've never heard of—don't miss MADAME RESTELL.”JILL FILIPOVIC, journalist and author of THE H-SPOT