Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

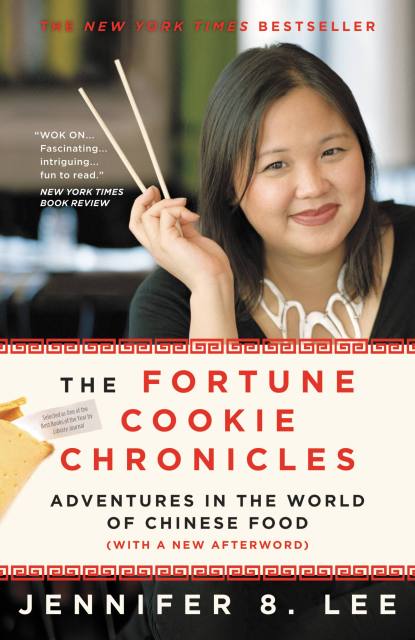

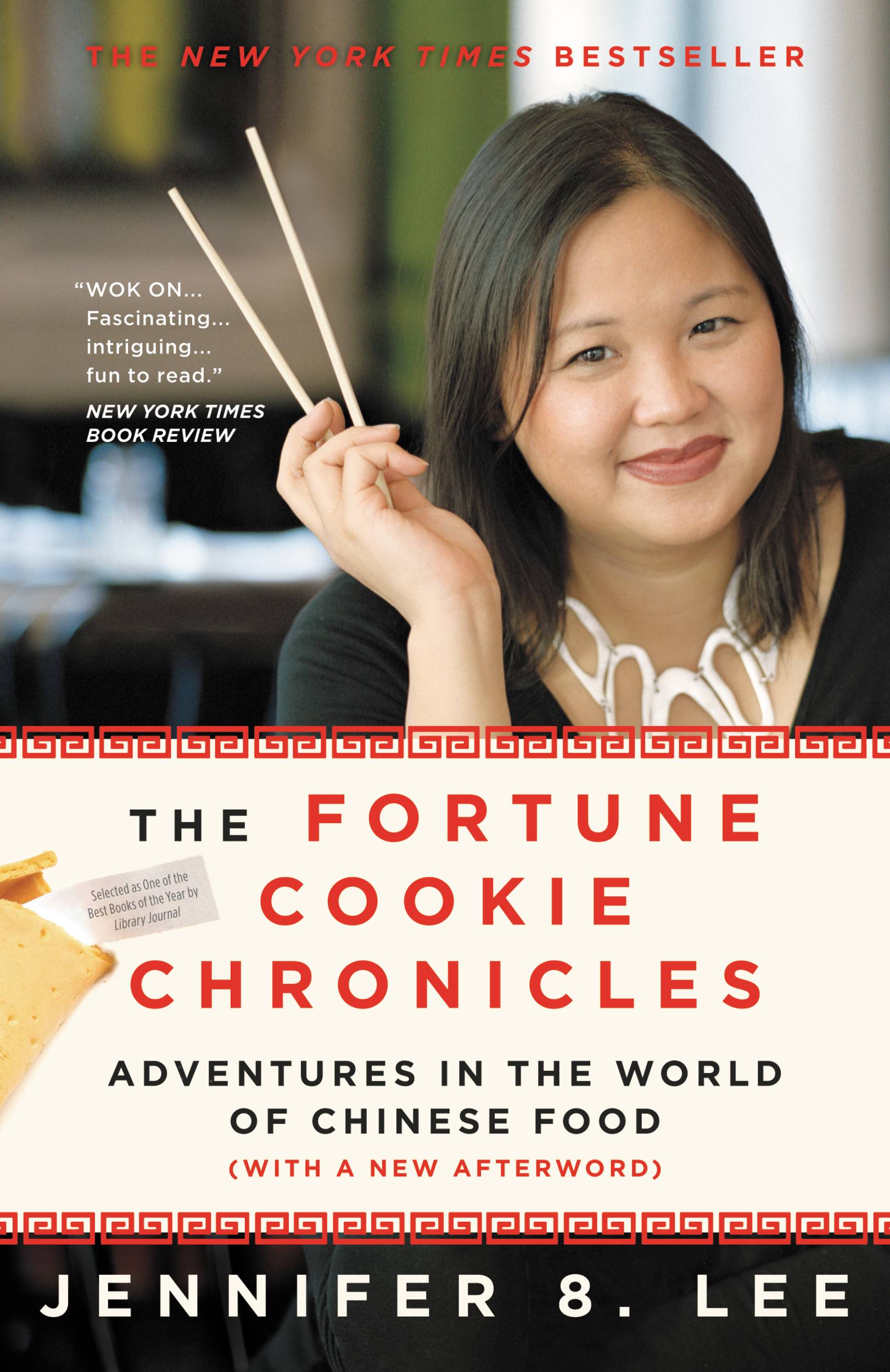

The Fortune Cookie Chronicles

Adventures in the World of Chinese Food

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Prices

- Sale Price $2.99

- Regular Price $9.99

- Discount (70% off)

Prices

- Sale Price $2.99 CAD

- Regular Price $12.99 CAD

- Discount (77% off)

Format

Format:

- ebook $2.99 $2.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 3, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

If you think McDonald’s is the most ubiquitous restaurant experience in America, consider that there are more Chinese restaurants in America than McDonalds, Burger Kings, and Wendys combined. New York Times reporter and Chinese-American (or American-born Chinese). In her search, Jennifer 8 Lee traces the history of Chinese-American experience through the lens of the food. In a compelling blend of sociology and history, Jenny Lee exposes the indentured servitude Chinese restaurants expect from illegal immigrant chefs, investigates the relationship between Jews and Chinese food, and weaves a personal narrative about her own relationship with Chinese food.

The Fortune Cookie Chronicles speaks to the immigrant experience as a whole, and the way it has shaped our country.

The Fortune Cookie Chronicles speaks to the immigrant experience as a whole, and the way it has shaped our country.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 3, 2008

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9780446511704

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use