Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

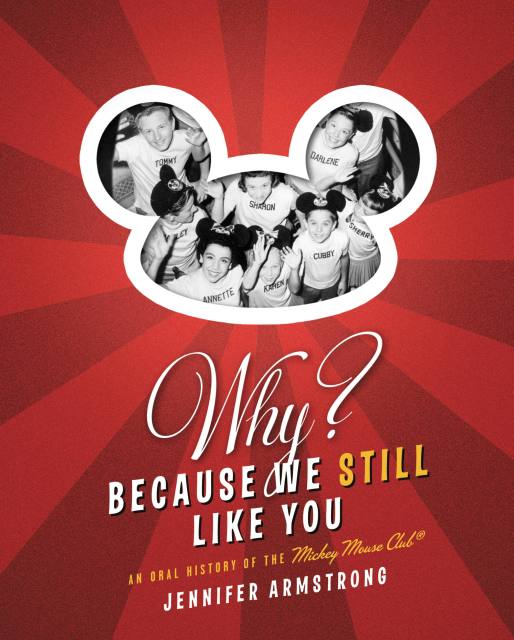

Why? Because We Still Like You

An Oral History of the Mickey Mouse Club(R)

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook (Digital original) $11.99 $15.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 29, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

From the bestselling author of Sienfeldia, a behind-the-scenes history of the Mickey Mouse Club that is a treat for anyone who grew up with Walt Disney’s television classic.

Full of nostalgia, this book gives you the never before told story of how The Mickey Mouse Club paved the way for all that came after, from its humble beginnings as a marketing ploy, through its short but mesmerizing run, to the numerous resurrections that made it one of television’s first true cult hits–all through the recollections of those regular kids-turned-stars who made it a phenomenon.

It will reveal, for the first time ever, the stories of Annette, Darlene (and her famous rivalry with Annette), Cubby and Karen, Bobbie and the rest of the beloved cast. It will explore, through the reminiscences of former fans who grew up to be some of television’s finest minds, what made the show so special. Finally, it will examine why the formula the creators of the show invented is more relevant than ever, and whether we’ll ever see yet another Club for a new generation.

Take a trip down memory lane with the original Mickey Mouse Club cast and creators, through drama and unexpected fame, to see how an television institution came into being.

Full of nostalgia, this book gives you the never before told story of how The Mickey Mouse Club paved the way for all that came after, from its humble beginnings as a marketing ploy, through its short but mesmerizing run, to the numerous resurrections that made it one of television’s first true cult hits–all through the recollections of those regular kids-turned-stars who made it a phenomenon.

It will reveal, for the first time ever, the stories of Annette, Darlene (and her famous rivalry with Annette), Cubby and Karen, Bobbie and the rest of the beloved cast. It will explore, through the reminiscences of former fans who grew up to be some of television’s finest minds, what made the show so special. Finally, it will examine why the formula the creators of the show invented is more relevant than ever, and whether we’ll ever see yet another Club for a new generation.

Take a trip down memory lane with the original Mickey Mouse Club cast and creators, through drama and unexpected fame, to see how an television institution came into being.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 29, 2010

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780446574341

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use