By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

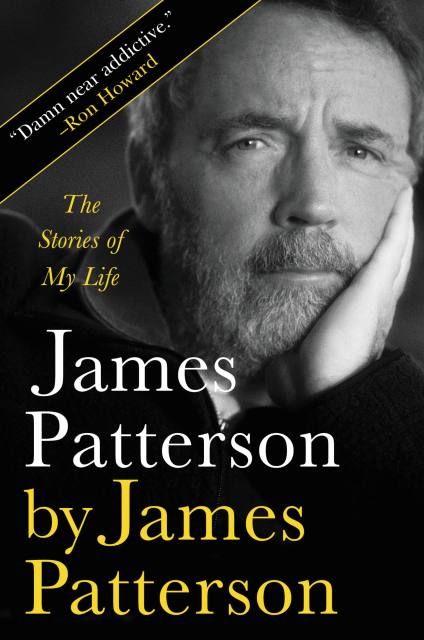

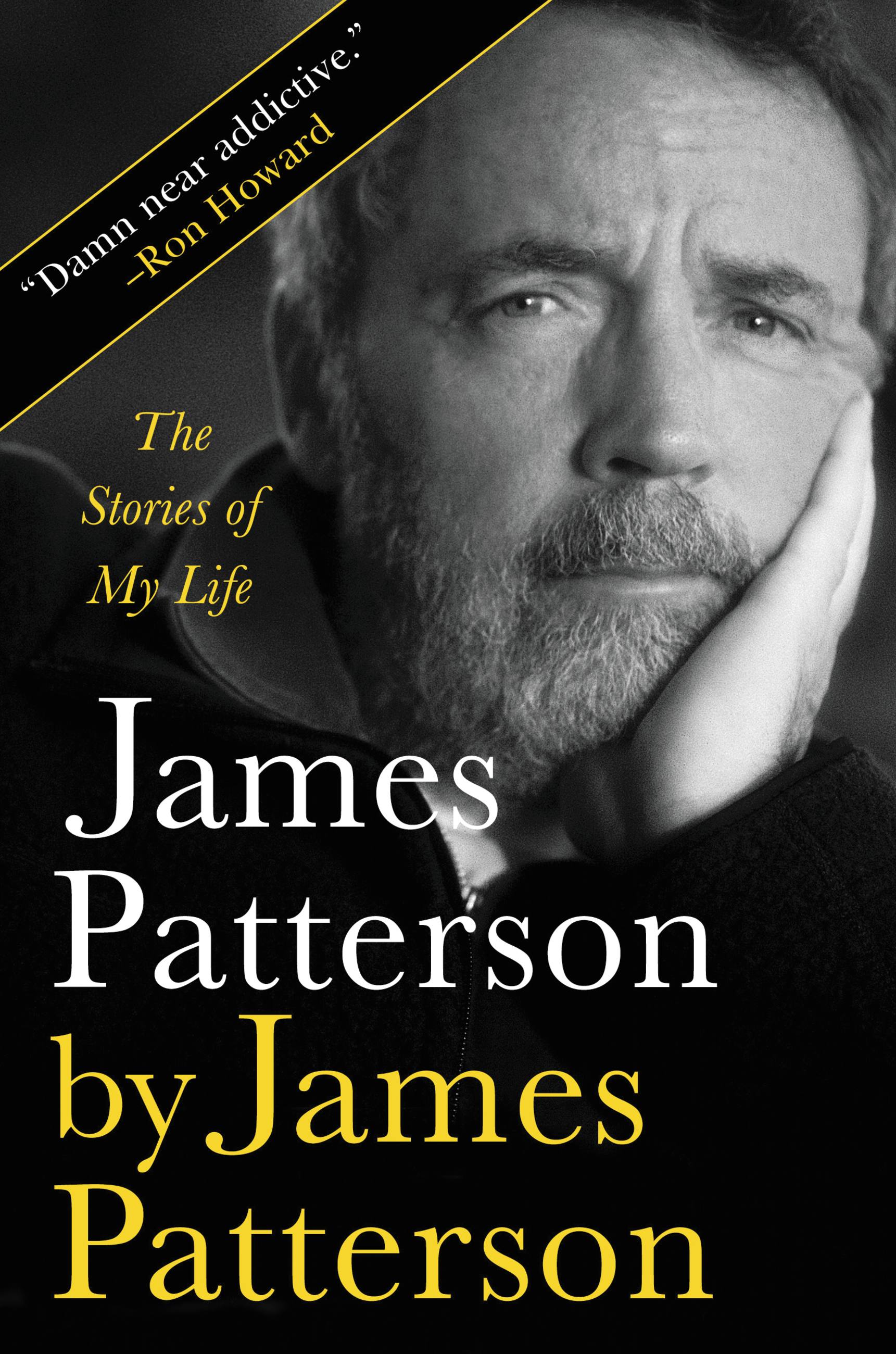

James Patterson by James Patterson

The Stories of My Life

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 6, 2022

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316397537

Price

$29.00Price

$37.00 CADFormat

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 6, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

How did a kid whose dad lived in the poorhouse become the world’s #1 bestselling author?

·On the morning he was born, he nearly died.

·His dad grew up in the Pogey– the Newburgh, New York, poorhouse.

·He worked at a mental hospital in Massachusetts, where he met the singer James Taylor and the poet Robert Lowell.

·While he toiled in advertising hell, James wrote the ad jingle line “I’m a Toys ‘R’ Us Kid.”

·He once watched James Baldwin and Norman Mailer square off to trade punches at a party.

·He’s only been in love twice. Both times are amazing.

·Dolly Parton once sang “Happy Birthday” to James over the phone. She calls him J.J., for Jimmy James.

He always wanted to write the kind of novel that would be read and reread so many times that the binding breaks and the book literally falls apart. As he says: “I’m still working on that one.”

“It’s quite a life, Patterson’s, and this fizzing, funny, often deeply moving memoir is a perfect way to understand the dizzying world of a best-selling writer.” —Daily Mail

“Damn near addictive. I loved it … that Patterson guy can write!” —Ron Howard

-

“One of the greatest storytellers of all time, Patterson has led an amazing life. James Patterson By James Patterson brings to mind Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast. I love the pithy, bright anecdotes, and at times his poignant narrative will bring you to tears.”New York Times bestselling author Patricia Cornwell

-

“The book was damn near addictive. I loved it. Patterson recounts turning points and life-shaping lessons in short, riveting bursts that inform, entertain, and satisfy—then propel you into the next story. That Patterson guy can write!”Ron Howard

-

“James Patterson does it again. The master storyteller of our times takes us on a funny, poignant, and ultimately triumphant journey through his own life. If you are among the many millions of us who enjoy reading Patterson’s books, or if you haven’t discovered him yet, you’ll love reading this one too.”Hillary Rodham Clinton

-

“I felt I was interviewing James Patterson under the highest permissible dose of sodium pentothal, the truth serum, for hours—and he spilled the whole story of his truly astonishing life and experiences and the absolute unlikelihood that he would become the best-selling fiction author of all time.”Bob Woodward

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use