Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

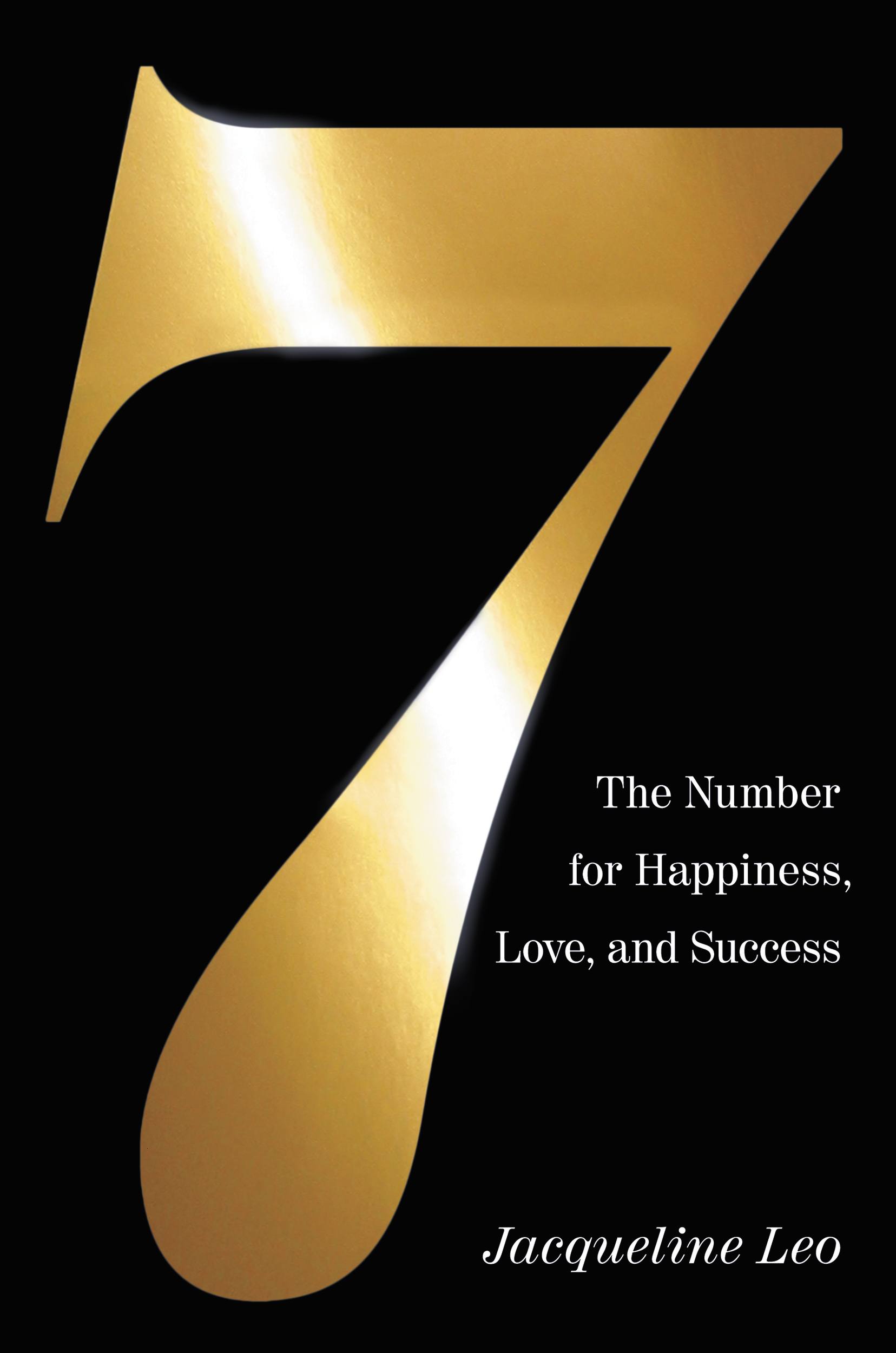

Seven

The Number for Happiness, Love, and Success

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$8.99Price

$10.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook (Digital original) $8.99 $10.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 7, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

What is it about the number seven that has such a hold on us? Why are there seven deadly sins? Seven days of the week? Seven wonders of the world, seven colors of the spectrum, seven ages of man, and seven sister colleges? Why can we hold seven numbers or words in our working memory–but no more? Author Jackie Leo explores everything about this mystical, magical, useful, and fun number in her new book.

Seven Reasons You Need This Book

1. SEVEN is a tool to improve the quality of your life. It is a way to define time, synthesize ideas, and keep your mind performing at top speed in an era of distractions.

2. SEVEN is culturally significant. It pops up everywhere, structuring our world in ways so fundamental, we notice them only when we pause to look. Across the ages and across cultures, the number has acquired a huge scientific, psychological, and religious significance.

3. SEVEN is intriguing. Why, out of hundreds of recipes in a cookbook, do people return to the same seven, over and over? Why, when asked to choose a number between one and ten, does such a large majority of people choose seven? Why does it take seven rounds of shuffling to obtain a fully mixed deck of cards?

4. SEVEN is influential. You’ll learn how the number seven shapes our thinking, our choices, and even our relationships.

5. SEVEN is practical. Throughout this book are Top Seven lists covering the best ways to get someone’s attention, to build your personal brand, and to put yourself in the path of prosperity and good luck.

6. SEVEN is fun. You’ll encounter surprising facts, intriguing puzzles, and hilarious anecdotes.

7. SEVEN is wise. You’ll hear stories about the meaning of seven from Mehmet Oz, Sally Quinn, Liz Smith, Christina Ricci, and many others.

Artfully designed and full of enough insights to keep you engaged in conversation at the water cooler for years, SEVEN will provoke, enlighten, and amuse.

Seven Reasons You Need This Book

1. SEVEN is a tool to improve the quality of your life. It is a way to define time, synthesize ideas, and keep your mind performing at top speed in an era of distractions.

2. SEVEN is culturally significant. It pops up everywhere, structuring our world in ways so fundamental, we notice them only when we pause to look. Across the ages and across cultures, the number has acquired a huge scientific, psychological, and religious significance.

3. SEVEN is intriguing. Why, out of hundreds of recipes in a cookbook, do people return to the same seven, over and over? Why, when asked to choose a number between one and ten, does such a large majority of people choose seven? Why does it take seven rounds of shuffling to obtain a fully mixed deck of cards?

4. SEVEN is influential. You’ll learn how the number seven shapes our thinking, our choices, and even our relationships.

5. SEVEN is practical. Throughout this book are Top Seven lists covering the best ways to get someone’s attention, to build your personal brand, and to put yourself in the path of prosperity and good luck.

6. SEVEN is fun. You’ll encounter surprising facts, intriguing puzzles, and hilarious anecdotes.

7. SEVEN is wise. You’ll hear stories about the meaning of seven from Mehmet Oz, Sally Quinn, Liz Smith, Christina Ricci, and many others.

Artfully designed and full of enough insights to keep you engaged in conversation at the water cooler for years, SEVEN will provoke, enlighten, and amuse.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Dec 7, 2009

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9780446552202

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use