By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

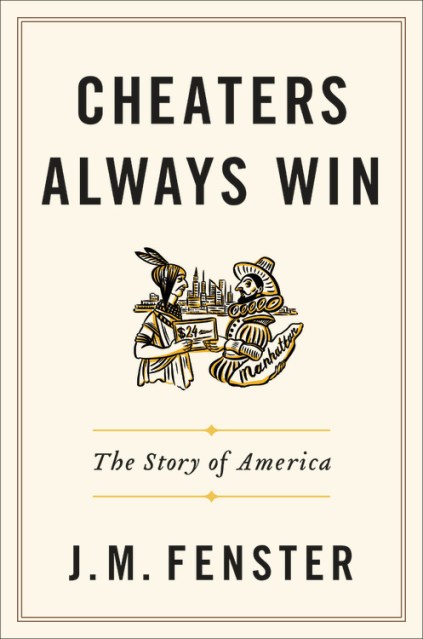

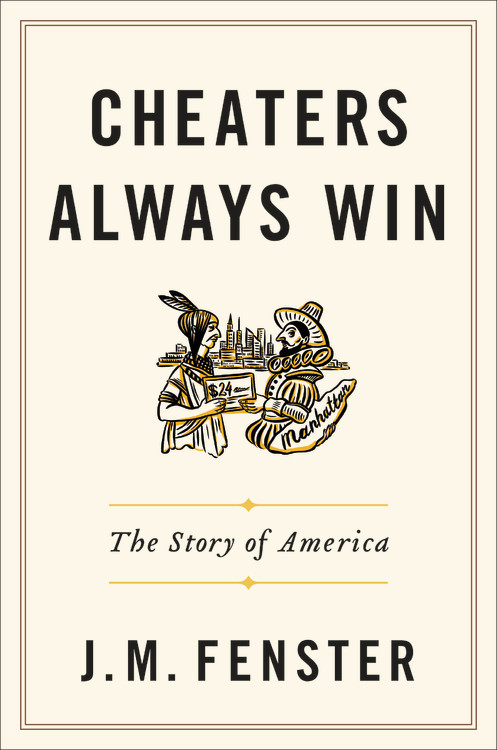

Cheaters Always Win

The Story of America

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 3, 2019

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781538728703

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 3, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Drawing from the intriguing (and sometimes unbelievable) true stories of the lives of everyday Americans, historian Julie M. Fenster traces the history of the weakening of our national ethics through the practice of cheating. From marital infidelity to financial fraud; rigged sports competitions to corruption in politics and the American education system; nuclear weaponry to beauty pageants; hospitals, TV gameshows, and charities; nothing and no one is exempt.

And far from being ostracized, cheaters in every sphere continue to survive and even thrive, casting their influence over the rest of our society. And nowhere is this more obvious than in the recent tectonic shift in politics, where a revolution in our collective attitude toward fraudsters has ushered in a new kind of leadership.

Part history of an all-American tradition, part dissection of an ongoing national crisis, Cheaters Always Win is irresistible reading — a smart, sardonic, and scintillating look into the practice that made America what it is today.

Genre:

-

"With her trademark panache and wit on fine display, J.M. Fenster brilliantly unmasks the epidemic of casual dishonesty that is corroding our democratic culture and civic life. Cheaters Always Win sparkles with historical vignettes, sardonic humor, and homespun pluck. An elegant page-turner for the ages!"Douglas Brinkley, New York Times bestselling author of Moonshot and The Boys of Pointe du Hoc

-

"Reading Cheaters Always Win is like listening to a really smart and witty friend tell you things you never knew about a subject you never properly thought through. Educational and fun."John Strausbaugh, award-winning author of City of Sedition and Victory City

-

"J. M. Fenster's new book is every bit as entertaining as it is important, for she tells a dazzling variety of often hilarious stories while brilliantly illuminating an increasingly crucial -- like it or not -- aspect of the character of almost all of us."Frederick E. Allen, former managing editor, American Heritage

-

"If one of your occasional crank rages is that yesterday's round of golf, your job, that car deal, your marriage, that new reality show, some presidential election...is just way off because someone is cheating, then Fenster has written a book packed with unexpected, hilarious, and sardonic proof that you're not paranoid at all."Jack Hitt, author of Bunch of Amateurs: Inside America's Hidden World of Inventors, Tinkerers, and Job Creators

-

"Timely...A lighthearted romp through several centuries of cheating at popular American pursuits."Kirkus

-

"Thoroughly entertaining...From the banal marital affair to cutthroat political backbiting, Cheaters Always Win spotlights America's can't-quit-you-baby relationship with deception. Wickedly fascinating."Daily Beast

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use