Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

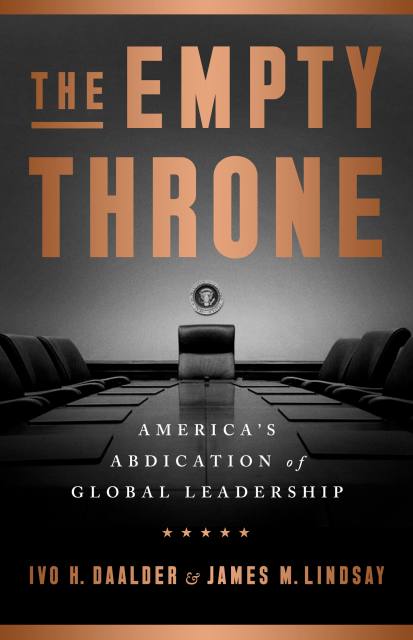

The Empty Throne

America's Abdication of Global Leadership

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 16, 2018

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541773875

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 16, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

America emerged from the catastrophe of World War II convinced that global engagement and leadership were essential to prevent another global conflict and further economic devastation. That choice was not inevitable, but its success proved monumental. It brought decades of great power peace, underpinned the rise in global prosperity, and defined what it meant to be an American in the eyes of the rest of the world for generations. It was an historic achievement.

Now, America has abdicated this vital leadership role. The Empty Throne is an inside portrait of the greatest lurch in US foreign policy since the decision to retreat back into Fortress America after World War I. The whipsawing of US policy has upended all that America’s postwar leadership created-strong security alliances, free and open markets, an unquestioned commitment to democracy and human rights. Impulsive, theatrical, ill-informed, backward-looking, bullying, and reckless are the qualities that the American president brings to the table, when he shows up at all. The world has had to absorb the spectacle of an America unmaking the world it made, and the consequences will be with us for years to come.

-

"A lively and authoritative account of the Trump administration's turbulent encounter with the outside world since the president took office in early 2017."Gideon Rachman, Financial Times