Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

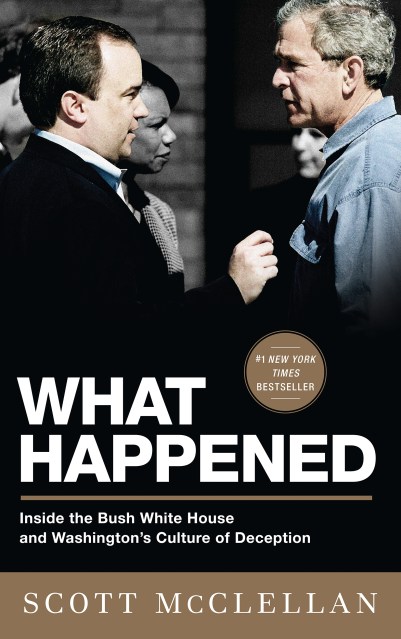

What Happened

Inside the Bush White House and Washington's Culture of Deception

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 3, 2008

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781586486525

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $11.99 $15.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 3, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In this refreshingly clear-eyed book, written with no agenda other than to record his experiences and insights for the benefit of history, McClellan provides unique perspective on what happened and why it happened the way it did, including the Iraq war, Hurricane Katrina, Washington’s bitter partisanship, and two hotly contested presidential campaigns. He gives readers a candid look into who George W. Bush is and what he believes, and into the personalities, strengths, and liabilities of his top aides. Finally, McClellan looks to the future, exploring the lessons this presidency offers the American people as we prepare to elect a new leader.