By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

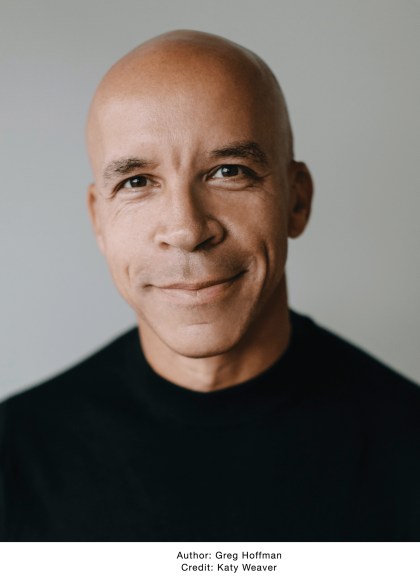

Emotion By Design

Creative Leadership Lessons from a Life at Nike

Contributors

By Greg Hoffman

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 5, 2022

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781538705599

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 5, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In EMOTION BY DESIGN, Hoffman shares lessons and stories on the power of creativity drawn from almost three decades of experience within Nike. A celebration of ingenuity and a call-to-arms for brand-builders to rediscover the human element in forming consumer bonds, EMOTION BY DESIGN is an insider’s guide to unlocking inspiration within a brand and building stronger emotional connections with consumers, using Hoffman’s three favorite guiding principles:

- Creativity is a Team Sport

- Dare to be Remembered

- Leave a Legacy, Not Just a Memory

With fascinating stories about Nike’s most famous campaigns, EMOTION BY DESIGN shares Hoffman’s philosophy and principles on how to create an empowering brand that resonates deeply with people by unlocking the creativity within your organization and unleashing it out into the world.

-

"The branding lessons in Greg Hoffman’s EMOTION BY DESIGN are invaluable for any business, big or small, and it gives you a blueprint for how Nike has created such strong emotional bonds with its consumers. Essential knowledge here.”Daymond John, New York Times bestselling author and co-star of "Shark Tank"

-

“A brand isn't a logo, it's a story. In this guidebook plus memoir, Greg helps us see how a commitment to our creative practice can make any story better.”Seth Godin, author of THE PRACTICE

-

“EMOTION BY DESIGN is Greg Hoffman's transformative and intensely personal journey building one of the world's most important, groundbreaking brands. It's a must-read if you work with creatives, and if you want to unlock their unique genius to build authentic brands and waves of support across your entire company.”Laszlo Bock, author of WORK RULES!

-

"Over his long career at Nike, Greg has implemented the art of design, simplicity, and creative collaboration, to connect to Nike’s millions of loyal consumers ... This inspirational approach, brought to life in the book, has been Greg’s legacy, and it’s given Nike a tremendous edge over its global competition.”Bob Greenberg, Founder and Executive Chairman of R/GA

-

"Filled with remarkable stories from Greg Hoffman’s time at Nike, EMOTION BY DESIGN offers a distinctive framework that will help marketers and creatives connect with their audiences like never before. Highly recommended."Jonah Berger, author of CONTAGIOUS

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use