Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

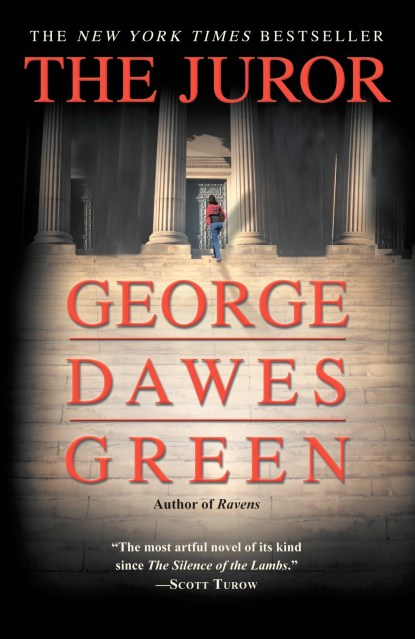

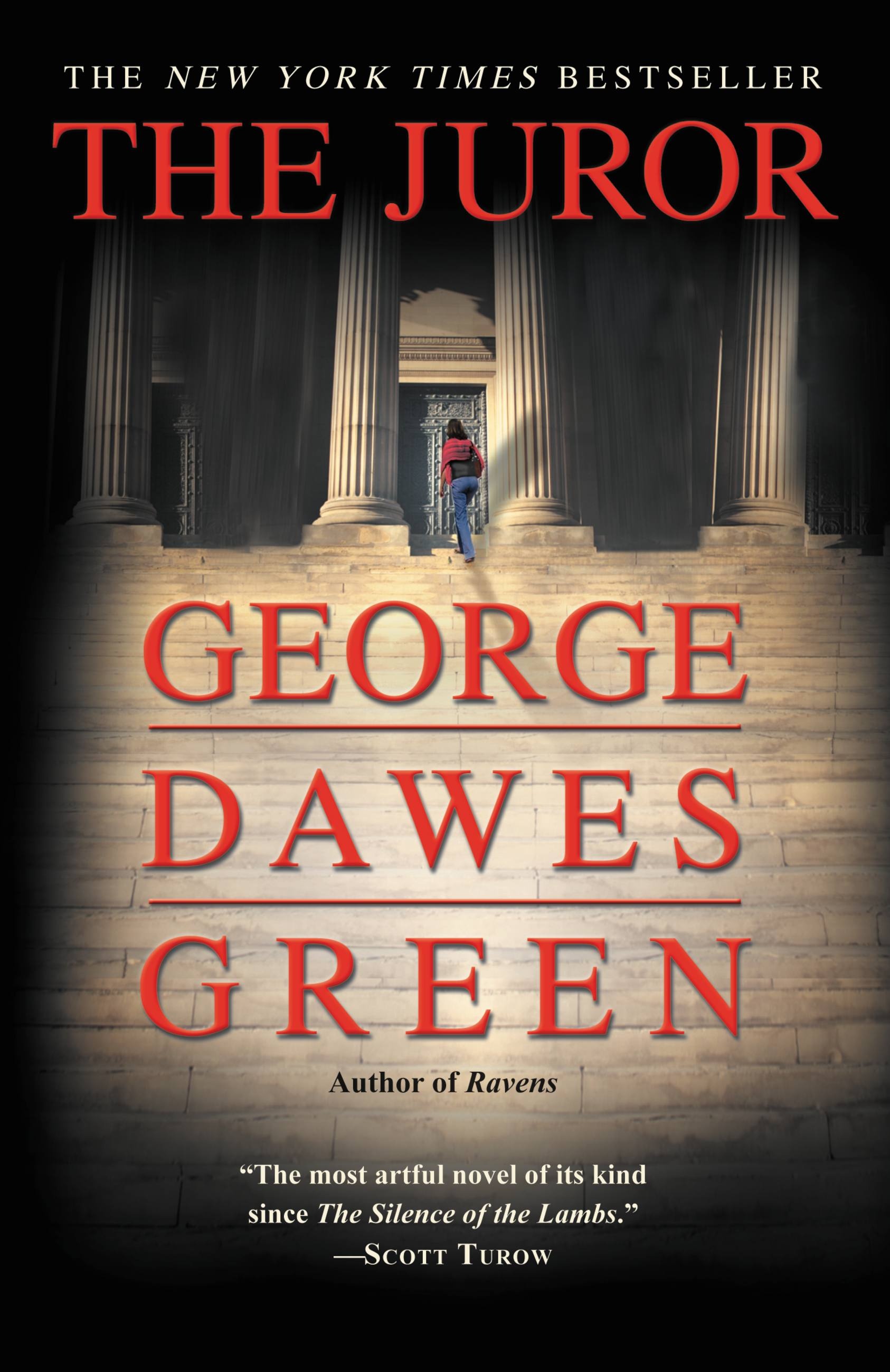

The Juror

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$24.99Price

$31.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Abridged) $18.99

- Audiobook CD (Abridged) $16.98 $18.98 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 24, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Pulled into the most chilling depths of the criminal underworld, Annie will be seduced by double-edged promises, stalked by the spector of terror, then, finally, driven to a shocking decision by the most basic motivation a woman can know. THE JUROR is a tour de force of crime and obsession, evil and innocence — a story that taps into fears so primal they linger long after the last page has been read.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jun 24, 2009

- Page Count

- 448 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780446550154

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use