Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

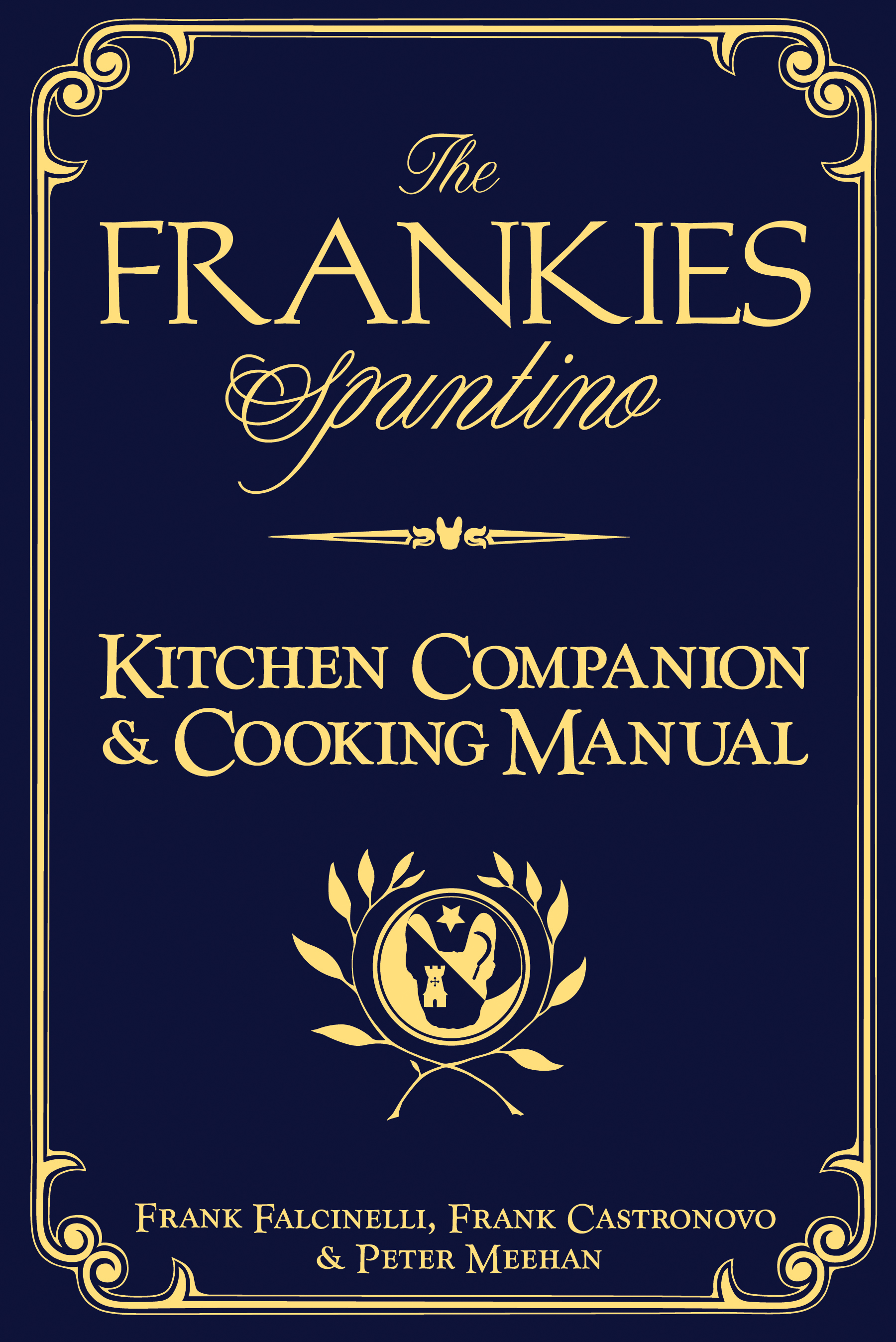

The Frankies Spuntino Kitchen Companion & Cooking Manual

Contributors

By Frank Falcinelli

By Peter Meehan

Formats and Prices

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 14, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

“Everything I made from the book . . . was surprisingly easy and just as delicious as what I’ve eaten at the restaurants.” —New York Times Book Review

From Brooklyn's sizzling restaurant scene, the hottest cookbook of the season…

From urban singles to families with kids, local residents to the Hollywood set, everyone flocks to Frankies Spuntino—a tin-ceilinged, brick-walled restaurant in Brooklyn's Carroll Gardens—for food that is "completely satisfying" (wrote Frank Bruni in The New York Times). The two Franks, both veterans of gourmet kitchens, created a menu filled with new classics: Italian American comfort food re-imagined with great ingredients and greenmarket sides. This witty cookbook, with its gilded edges and embossed cover, may look old-fashioned, but the recipes are just we want to eat now. The entire Frankies menu is adapted here for the home cook—from small bites including Cremini Mushroom and Truffle Oil Crostini, to such salads as Escarole with Sliced Onion & Walnuts, to hearty main dishes including homemade Cavatelli with Hot Sausage & Browned Butter. With shortcuts and insider tricks gleaned from years in gourmet kitchens, easy tutorials on making fresh pasta or tying braciola, and an amusing discourse on Brooklyn-style Sunday "sauce" (ragu), The Frankies Spuntino Kitchen Companion & Kitchen Manual will seduce both experienced home cooks and a younger audience that is newer to the kitchen.

From Brooklyn's sizzling restaurant scene, the hottest cookbook of the season…

From urban singles to families with kids, local residents to the Hollywood set, everyone flocks to Frankies Spuntino—a tin-ceilinged, brick-walled restaurant in Brooklyn's Carroll Gardens—for food that is "completely satisfying" (wrote Frank Bruni in The New York Times). The two Franks, both veterans of gourmet kitchens, created a menu filled with new classics: Italian American comfort food re-imagined with great ingredients and greenmarket sides. This witty cookbook, with its gilded edges and embossed cover, may look old-fashioned, but the recipes are just we want to eat now. The entire Frankies menu is adapted here for the home cook—from small bites including Cremini Mushroom and Truffle Oil Crostini, to such salads as Escarole with Sliced Onion & Walnuts, to hearty main dishes including homemade Cavatelli with Hot Sausage & Browned Butter. With shortcuts and insider tricks gleaned from years in gourmet kitchens, easy tutorials on making fresh pasta or tying braciola, and an amusing discourse on Brooklyn-style Sunday "sauce" (ragu), The Frankies Spuntino Kitchen Companion & Kitchen Manual will seduce both experienced home cooks and a younger audience that is newer to the kitchen.

Genre:

-

“The ingredient lists are short, the recipes are simple, flavorful, and easy to follow.”

—New York Times

“This witty guide showcases the ‘radically simple’ cooking philosophy of the chef-owners of Brooklyn's Frankies Spuntino. It presents pared-down Italian food full of flavor, not pretense.”

–Bon Appétit

“Everything I made from the book . . . was surprisingly easy and just as delicious as what I’ve eaten at the restaurants.”

–New York Times Book Review

“A cookbook that's as useful as it is artfully conceived.”

–GQ

“The team behind the popular Brooklyn eatery divulges light Italian secrets in this beautiful tome worthy of any bookshelf.”

–Entertainment Weekly

"When we’re craving the comforts of red sauce classics, the Frankie’s cookbook is full of reliable recipes guaranteed to keep us satiated."

—Time Out New York

“The book is a perfect reflection of the Franks’ philosophy of making the past the hippest part of the present.”

–Food Wine

“This quirky, lovely, intelligent cookbook is worth reading from cover to cover than starting over again.”

–Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

“Unfussy ingredients . . . surprisingly sophisticated.”

–Grub Street

- On Sale

- Jun 14, 2010

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Artisan

- ISBN-13

- 9781579654153

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use