By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

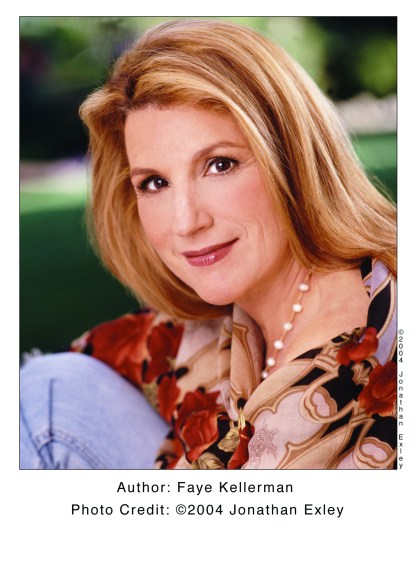

Street Dreams

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 1, 2003

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780759528161

Price

$7.99Price

$9.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $7.99 $9.99 CAD

- Hardcover (Large Print) $35.00 $45.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Abridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 1, 2003. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Now the hunt is on for the mother. Armed with advice from her overworked father, Detective Peter Decker, Cindy plunges into her inner-city Hollywood district, a world of helpless people and violent gangs. Pursuing each new lead batters her complex relationships and endangers her life.

On one side: Decker and Decker, a brilliant but combative pair. On the other: a vicious killer ready to strike again. While on routine patrol, LAPD officer Cindy Decker rescues a newborn abandoned in an alley dumpster. Cindy searches for the mother in inner -city Hollywood, following a treacherous trail filled with drug lords. But with each new lead, the twisted journey gets darker — and endangering her very life. When Decker and Decker join forces, can this edgy duo put personal issues aside to catch a vicious culprit before he strikes again?

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use