Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

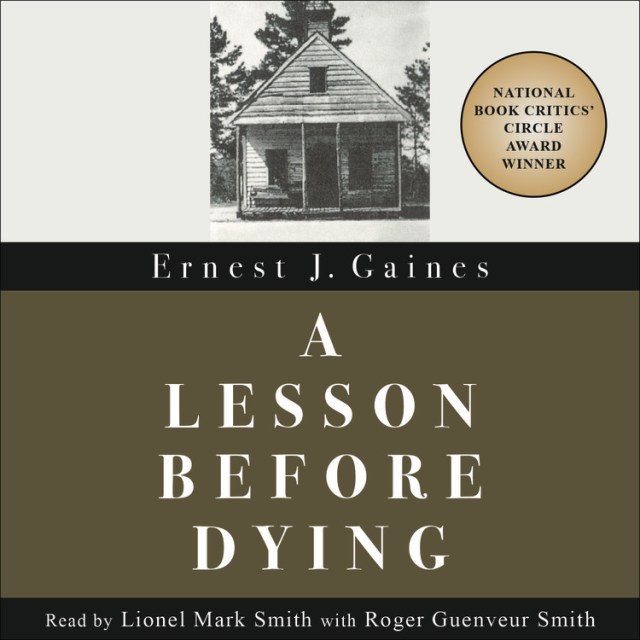

A Lesson Before Dying

Contributors

Read by Lionel Mark Smith

Read by Roger Guenveur Smith

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 1, 2006

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781594837647

Price

$14.98Format

Format:

Audiobook Download (Abridged) $14.98This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 1, 2006. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

This Pulitzer Prize winning book follows the real-life story of the friendship formed between a disheartened schoolteacher and a Black man falsely accused of murder in Jim Crow era Louisiana.

Based on Ernest J. Gaines’ National Book Critics Circle Award-winning novel, A Lesson Before Dying is set in a small Louisiana Cajun community in the late 1940s. Jefferson, a young illiterate black man, is falsely convicted of murder and is sentenced to death. Grant Wiggins, the plantation schoolteacher, agrees to talk with the condemned man.

Based on Ernest J. Gaines’ National Book Critics Circle Award-winning novel, A Lesson Before Dying is set in a small Louisiana Cajun community in the late 1940s. Jefferson, a young illiterate black man, is falsely convicted of murder and is sentenced to death. Grant Wiggins, the plantation schoolteacher, agrees to talk with the condemned man.

The disheartened Wiggins had once harbored dreams of escaping from his impoverished youth, yet he returned to his hometown after university, to teach children whose lives seemed as unpromising as Jefferson’s. The two men forge a bond as they come to understand what it means to resist and defy one’s fate.