By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

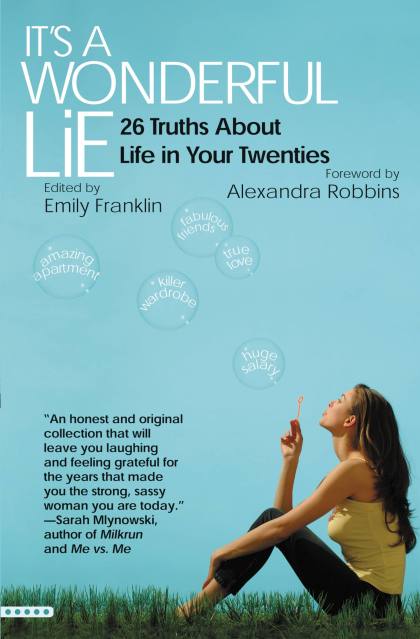

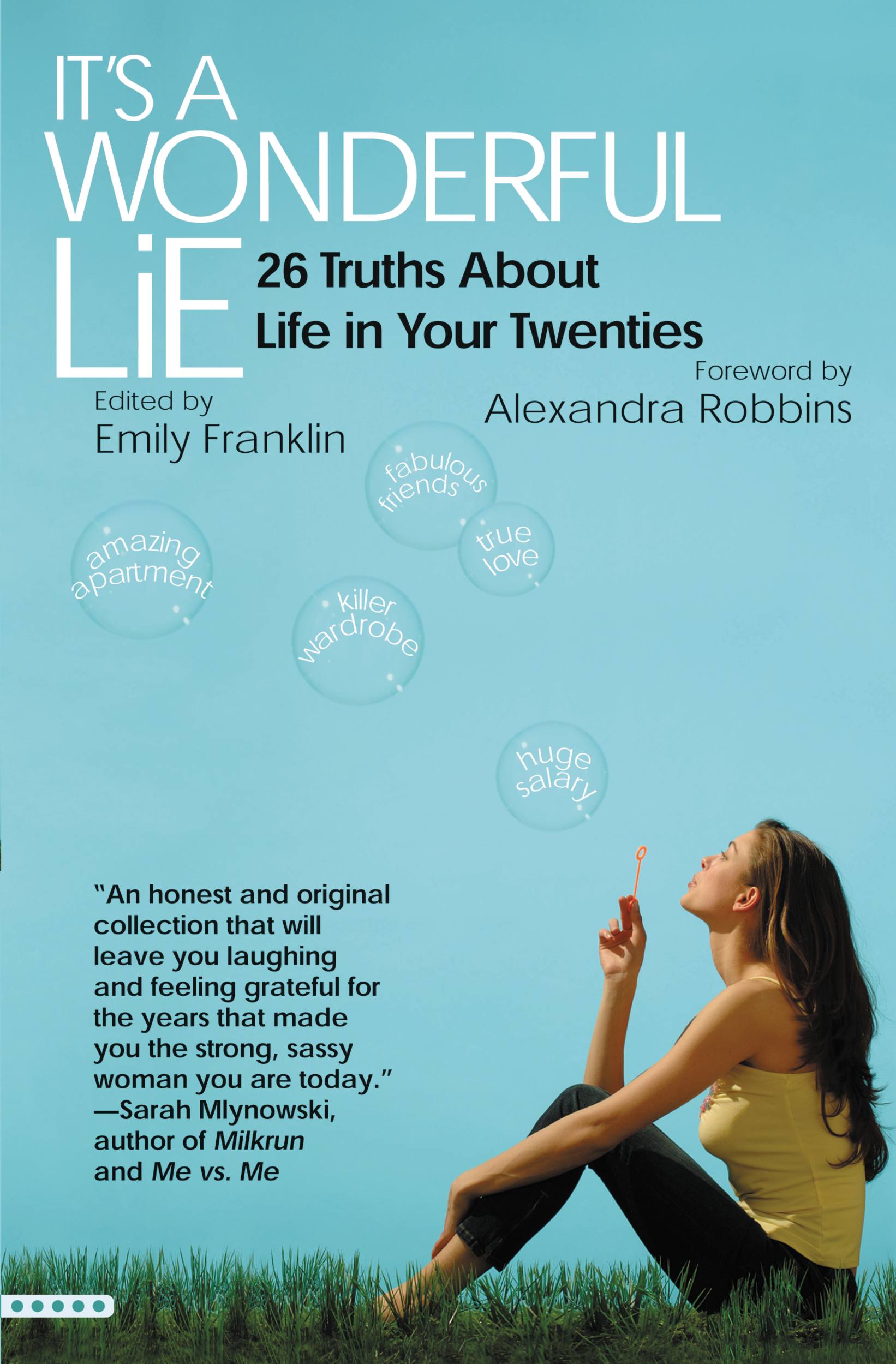

It’s a Wonderful Lie

26 Truths About Life in Your Twenties

Contributors

Foreword by Alexandra Robbins

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 3, 2007

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- 5 Spot

- ISBN-13

- 9780759516793

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook (Digital original) $9.99 $12.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 3, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The Bitch in the House meets Quarterlife Crisis in this sassy, smart, and honest collection, which includes 26 original essays about life as a 20-something female.

With essays titled “Homesick for the Place You’ve Never Been,” “A Letter to My Crappy One Bedroom,” “Breaking up (with Mastercard) is Hard to Do,” and “Hired, Fired, and What I Wore,” IT’S A WONDERFUL LIE takes a provocative look at what women are making of their 20-something selves.

Remarkable female writers, including Anna Maxted, Melissa Senate, and Beth Lisick, among others, share their experiences as they explore everything from their first jobs, loves, and losses, to the perils of uncontrolled debt and the pain of making new friends. Amusing, moving, and empowering, IT’S A WONDERFUL LIE is a must read for every woman in her 20s, and those who have learned, loved, and lived through them. At last, an anthology that considers what one should and should not expect from what she’s been led to believe are the best years of her life.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use