By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

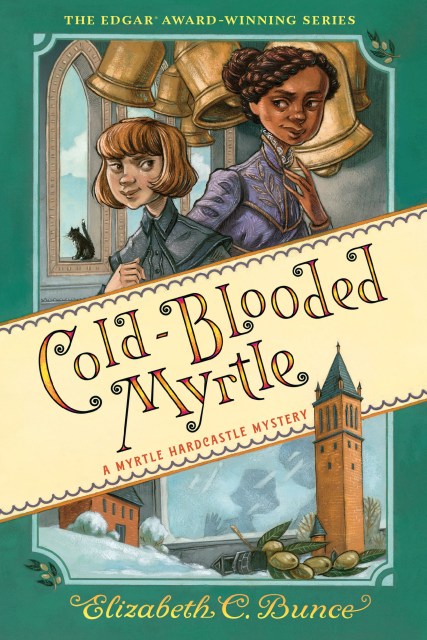

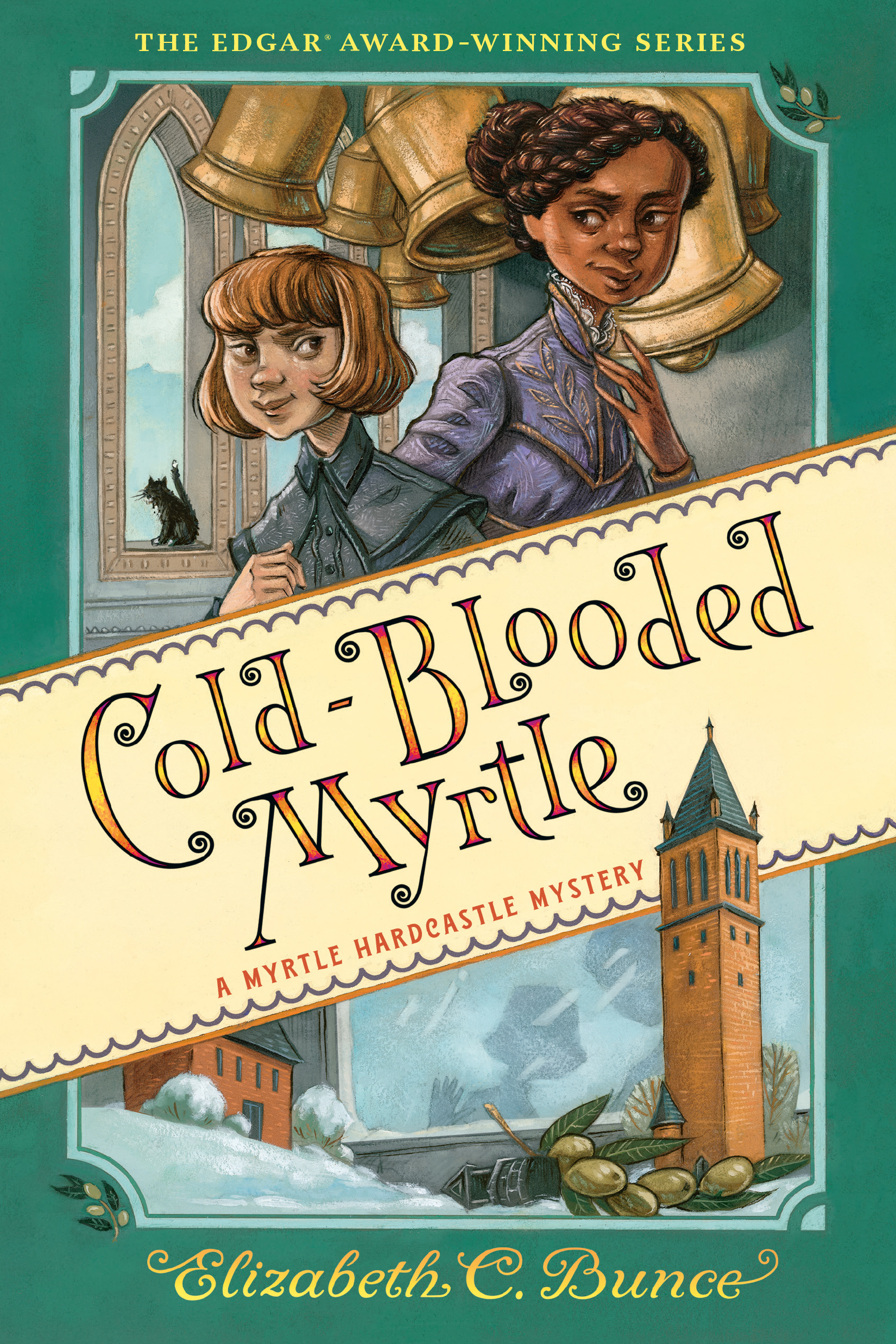

Cold-Blooded Myrtle (Myrtle Hardcastle Mystery 3)

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 4, 2022

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9781643753065

Price

$8.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $8.99 $12.99 CAD

- ebook $7.99 $9.99 CAD

- Hardcover $17.95 $23.95 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 4, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

An Edgar® Award Winning Series

Myrtle Hardcastle—twelve-year-old Young Lady of Quality and Victorian amateur detective—is back on the case, solving a string of bizarre murders in her hometown of Swinburne and picking up right where she left off in Premeditated Myrtle and How to Get Away with Myrtle.

When the proprietor of Leighton’s Mercantile is found dead on the morning his annual Christmas shop display is to be unveiled, it’s clear a killer had revenge in mind. But who would want to kill the local dry-goods merchant? Perhaps someone who remembers the mysterious scandal that destroyed his career as a professor and archaeologist. When the killer strikes again, each time manipulating the figures in the display to foretell the crime, Myrtle finds herself racing to uncover the long-buried facts of a cold case—and the motivations of a modern murderer.

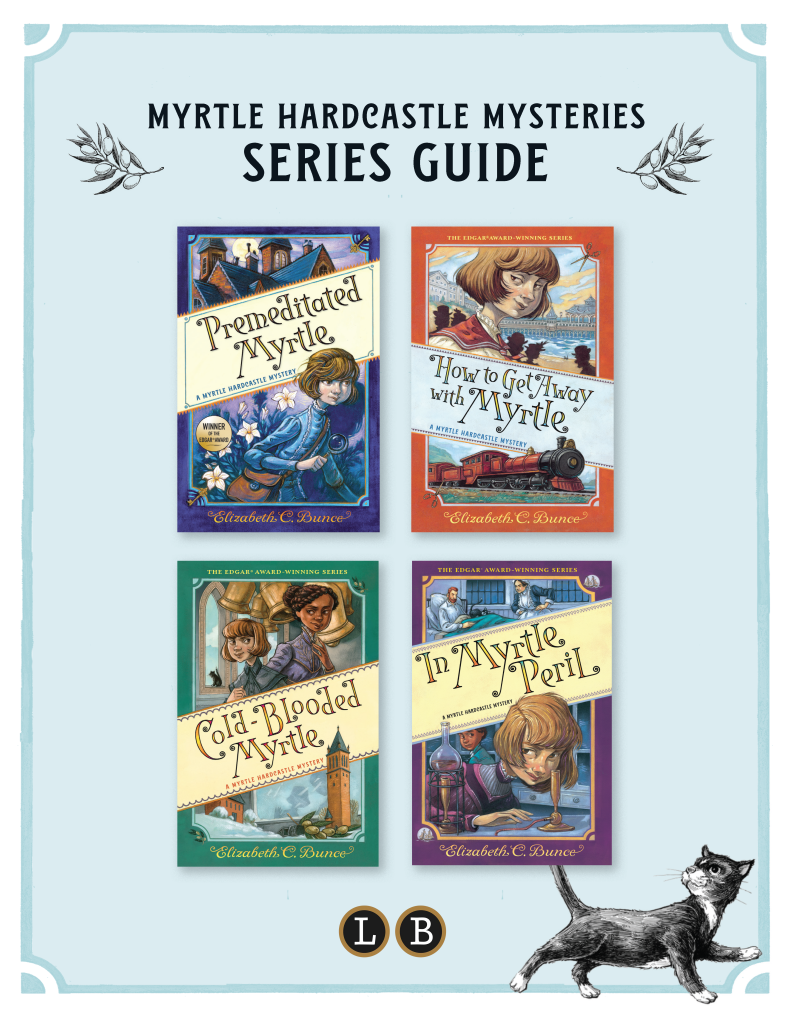

Series:

-

YA Books Central

“Younger Holmes fans (and older ones too) should be charmed by Elizabeth C. Bunce’s Cold-Blooded Myrtle.”

—Wall Street Journal, “Holiday Gift Books 2021: Mysteries”* “Comical footnotes pepper the text, adding wit to prose which is already dryly funny. Clues abound, giving astute readers the chance to solve the mystery along with Myrtle. Another excellent whodunit with a charming, snarky sleuth.”

I>Kirkus Reviews, starred review“This third mystery in the Myrtle Hardcastle series brings all the Victorian charm and flair of the first two as the smart, high-spirited protagonist unravels the who and why behind a series of murders in her hometown of Swinburne. Curious, witty and tenacious, Myrtle navigates an elegantly twisty plot to finally finger the villain – or does she? This compelling story will keep readers guessing till the very last page.”

I>Washington Parent

“The most entertaining whodunit yet in this terrific series set in Victorian England. … Narrated in Myrtle’s smart, irreverent voice and peppered with amusing footnotes, the novel builds suspense as the body count rises right up to the dramatic finale.”

I>The Buffalo News“This series is a great way to introduce younger readers to this genre. There are plenty of clues to file away and figure out, and the twists and turns end in a very satisfying way! . . . Readers who enjoyed mysteries like [Taryn] Souders' Coop Knows the Scoop, [Kristin L.] Gray's The Amelia Six, and the work of Stuart Gibbs will find Myrtle a great introduction to the Victorian era and a keen detective when it comes to figuring out murders!”

Enhanced Book Club Kit

Myrtle Hardcastle Series Guide