By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

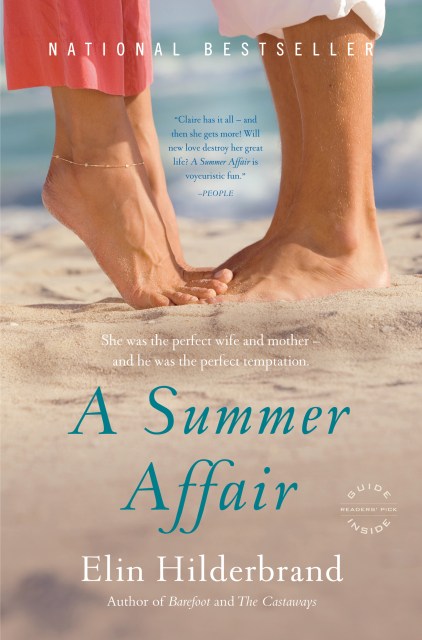

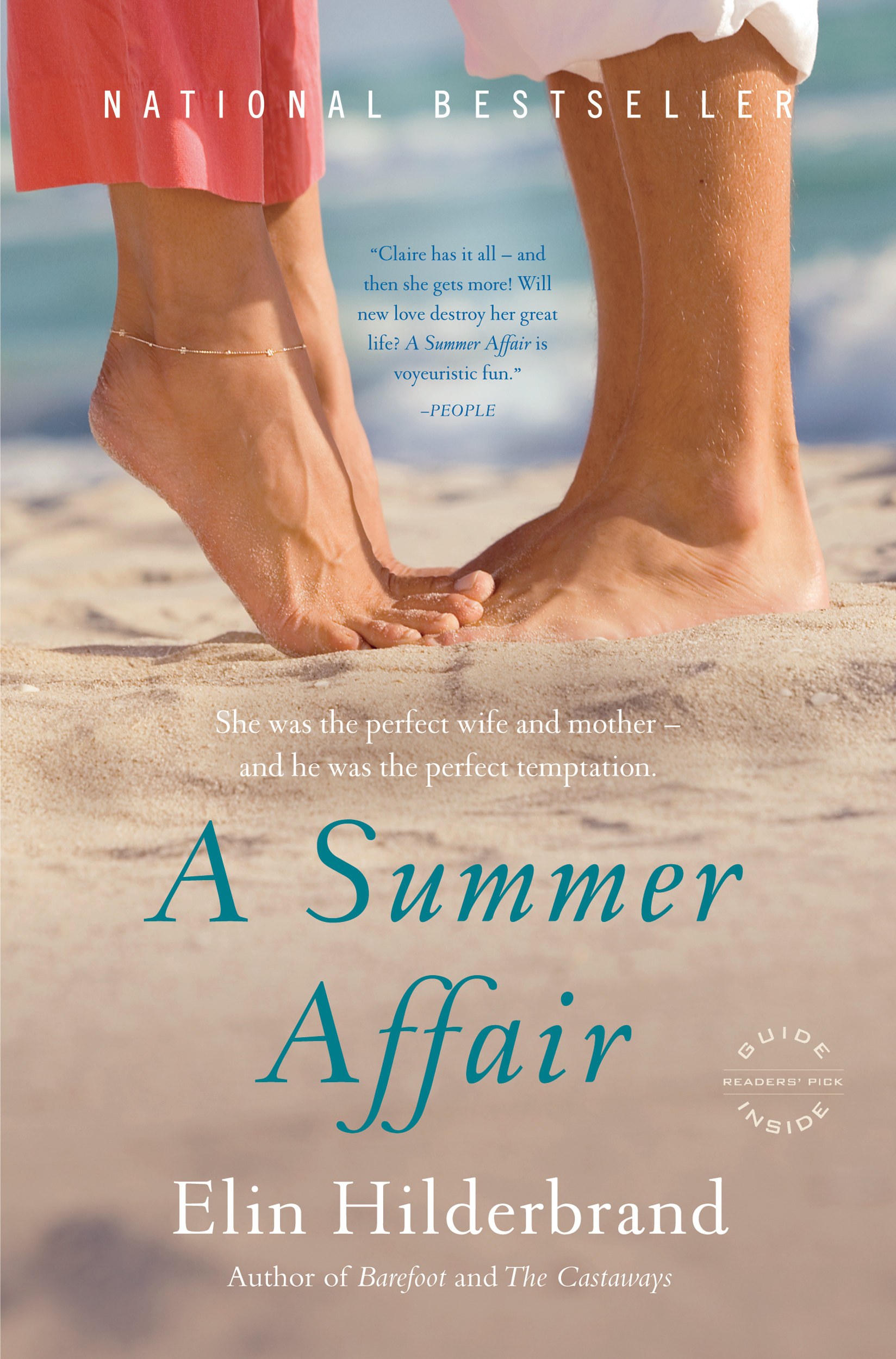

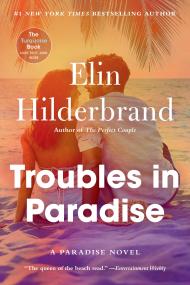

A Summer Affair

A Novel

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 2, 2008

- Page Count

- 512 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316032674

Price

$8.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 2, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The perfect wife and mother finds the perfect temptation in this "perfect summer cocktail of sex, sun, and scandal" (Kirkus Reviews).

Claire has a problem with setting limits. All her life she has taken on every responsibility, assumed every burden, granted every request. Claire wants it all—and in the eyes of her friends, she has it: a devoted husband, four beautiful children, even a successful career as an artist. So when she agrees to chair the committee for Nantucket's social event of the year, she knows she can handle it. Claire can handle anything.

But when planning the gala propels her into the orbit of billionaire Lock Dixon, unexpected sparks begin to fly. Lock insists on working closely with Claire—often over a bottle of wine—and before long she can't ignore the subtle touches and lingering looks. To her surprise, she can't ignore how they make her feel, either. Claire finds the gala, her life, and herself spinning out of control.

A Summer Affair captures the love, loss, and limbo of an illicit romance and unchecked passion as it takes us on a brave and breathless journey into the heart of one modern woman.

"Think you know where this is going? Think again. Hilderbrand is way too smart to give away the whole story in her title." —Elisabeth Egan, New York Times

Claire has a problem with setting limits. All her life she has taken on every responsibility, assumed every burden, granted every request. Claire wants it all—and in the eyes of her friends, she has it: a devoted husband, four beautiful children, even a successful career as an artist. So when she agrees to chair the committee for Nantucket's social event of the year, she knows she can handle it. Claire can handle anything.

But when planning the gala propels her into the orbit of billionaire Lock Dixon, unexpected sparks begin to fly. Lock insists on working closely with Claire—often over a bottle of wine—and before long she can't ignore the subtle touches and lingering looks. To her surprise, she can't ignore how they make her feel, either. Claire finds the gala, her life, and herself spinning out of control.

A Summer Affair captures the love, loss, and limbo of an illicit romance and unchecked passion as it takes us on a brave and breathless journey into the heart of one modern woman.

"Think you know where this is going? Think again. Hilderbrand is way too smart to give away the whole story in her title." —Elisabeth Egan, New York Times

Genre:

-

"Think you know where this is going? Think again. Hilderbrand is way too smart to give away the whole story in her title."Elizabeth Egan, New York Times

-

"Claire has it all — and then she gets more! Will new love destroy her great life? A Summer Affair is voyeuristic fun."People

-

"A gem of a summer read with a glamorous location, elite lifestyle, and Hilderbrand's appealing take on the constant stress that fills the lives of women everywhere."Booklist

-

"A perfect summer cocktail of sex, sun, and scandal.... Pure voyeuristic fun."Kirkus Reviews

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use