Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

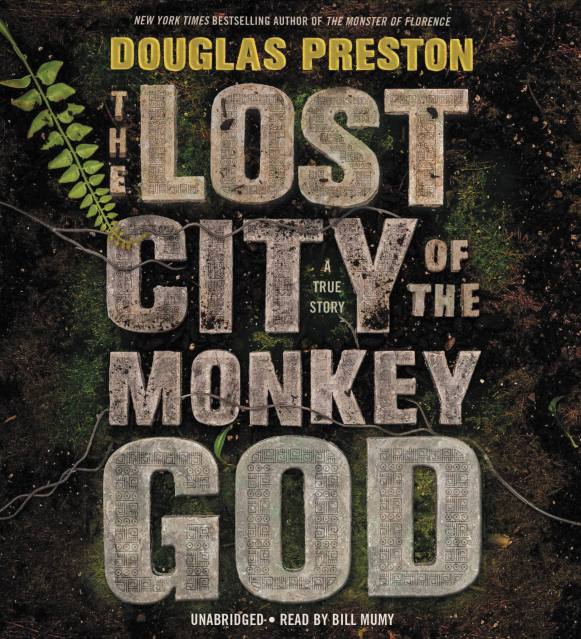

The Lost City of the Monkey God

A True Story

Contributors

Read by Bill Mumy

Formats and Prices

Price

$20.00Price

$26.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Audiobook CD (Unabridged) $20.00 $26.00 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover (Large Print) $43.00 $54.00 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $39.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 5, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Since the days of conquistador Hernán Cortés, rumors have circulated about a lost city of immense wealth hidden somewhere in the Honduran interior, called the White City or the Lost City of the Monkey God. Indigenous tribes speak of ancestors who fled there to escape the Spanish invaders, and they warn that anyone who enters this sacred city will fall ill and die. In 1940, swashbuckling journalist Theodore Morde returned from the rainforest with hundreds of artifacts and an electrifying story of having found the Lost City of the Monkey God-but then committed suicide without revealing its location.

Three quarters of a century later, bestselling author Doug Preston joined a team of scientists on a groundbreaking new quest. In 2012 he climbed aboard a rickety, single-engine plane carrying the machine that would change everything: lidar, a highly advanced, classified technology that could map the terrain under the densest rainforest canopy. In an unexplored valley ringed by steep mountains, that flight revealed the unmistakable image of a sprawling metropolis, tantalizing evidence of not just an undiscovered city but an enigmatic, lost civilization.

Venturing into this raw, treacherous, but breathtakingly beautiful wilderness to confirm the discovery, Preston and the team battled torrential rains, quickmud, disease-carrying insects, jaguars, and deadly snakes. But it wasn’t until they returned that tragedy struck: Preston and others found they had contracted in the ruins a horrifying, sometimes lethal-and incurable-disease.

Suspenseful and shocking, filled with colorful history, hair-raising adventure, and dramatic twists of fortune, THE LOST CITY OF THE MONKEY GOD is the absolutely true, eyewitness account of one of the great discoveries of the twenty-first century.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 5, 2017

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781478988229

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use