By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

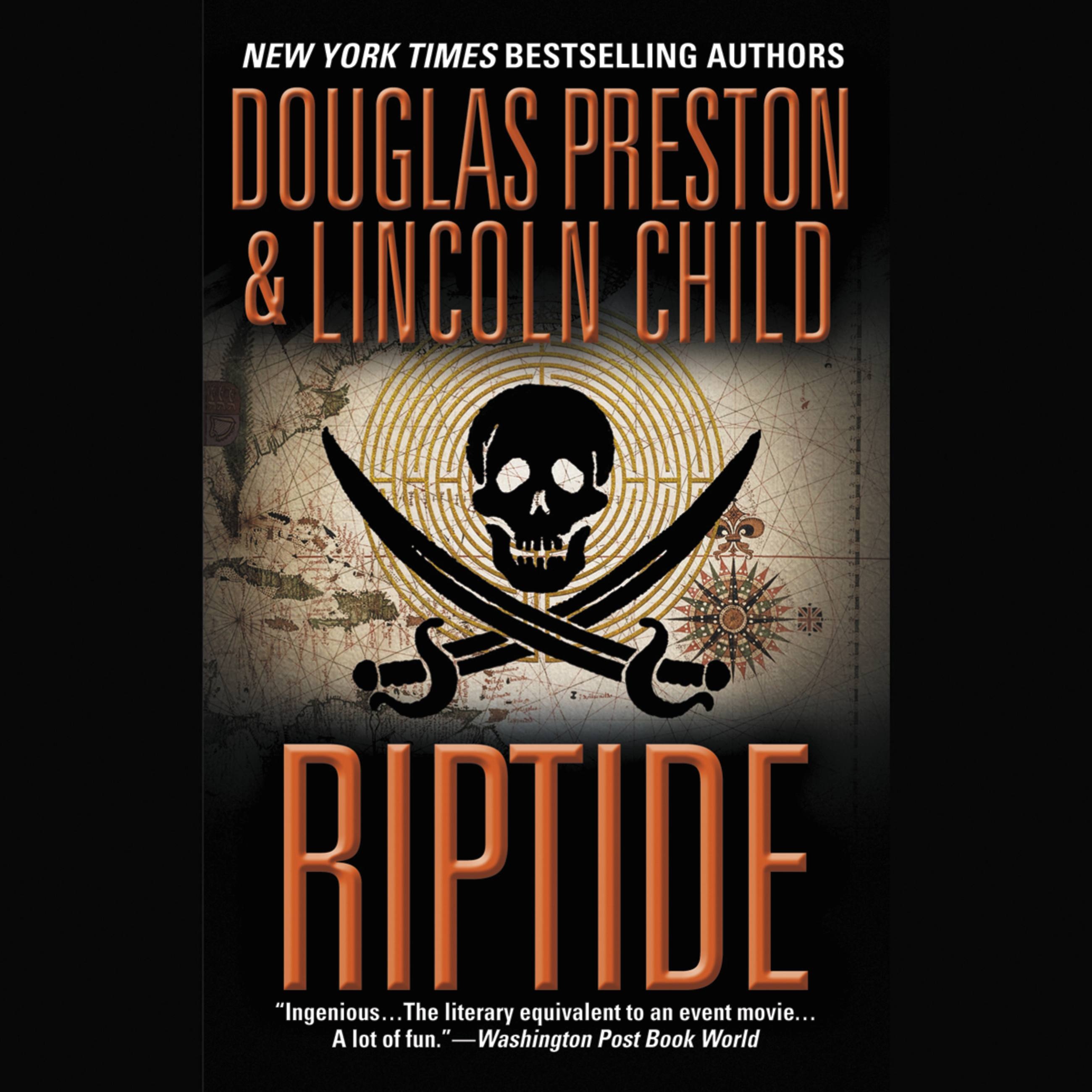

Riptide

Contributors

Read by Scott Brick

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 3, 2010

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781607884729

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook $7.99 $9.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $39.00 CAD

- Mass Market $9.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 3, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

IN 1695, a notorious English pirate buried his bounty in a maze of booby-trapped tunnels on an island off the coast of Maine. In three hundred years, no one has breached this cursed and rocky fortress. Now a treasure hunter and his high-tech, million-dollar recovery team embark on the perfect operation to unlock the labyrinth’s mysteries. First the computers fail. The then crewmen begin to die. The island has guarded its secrets for centuries, and it isn’t letting them go–without a fight.