Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

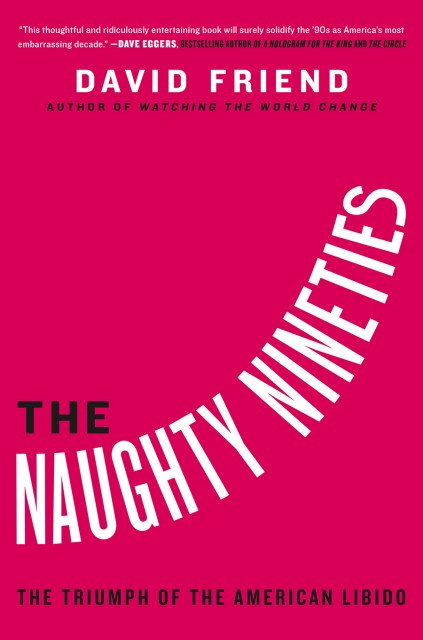

The Naughty Nineties

The Triumph of the American Libido

Contributors

By David Friend

Formats and Prices

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Hardcover $32.00 $42.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $44.99

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 12, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A sexual history of the 1990s when the Baby Boomers took over Washington, Hollywood, and Madison Avenue. A definitive look at the captains of the culture wars — and an indispensable road map for understanding how we got to the Trump Teens.

The Naughty Nineties: The Triumph of the American Libido examines the scandal-strafed decade when our public and private lives began to blur due to the rise of the web, reality television, and the wholesale tabloidization of pop culture.

In this comprehensive and often hilarious time capsule, David Friend combines detailed reporting with first-person accounts from many of the decade’s singular personalities, from Anita Hill to Monica Lewinsky, Lorena Bobbitt to Heidi Fleiss, Alan Cumming to Joan Rivers, Jesse Jackson to key members of the Clinton, Dole, and Bush teams.

The Naughty Nineties also uncovers unsung sexual pioneers, from the enterprising sisters who dreamed up the Brazilian bikini wax to the scientists who, quite by accident, discovered Viagra.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 12, 2017

- Page Count

- 608 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781455567553

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use