By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

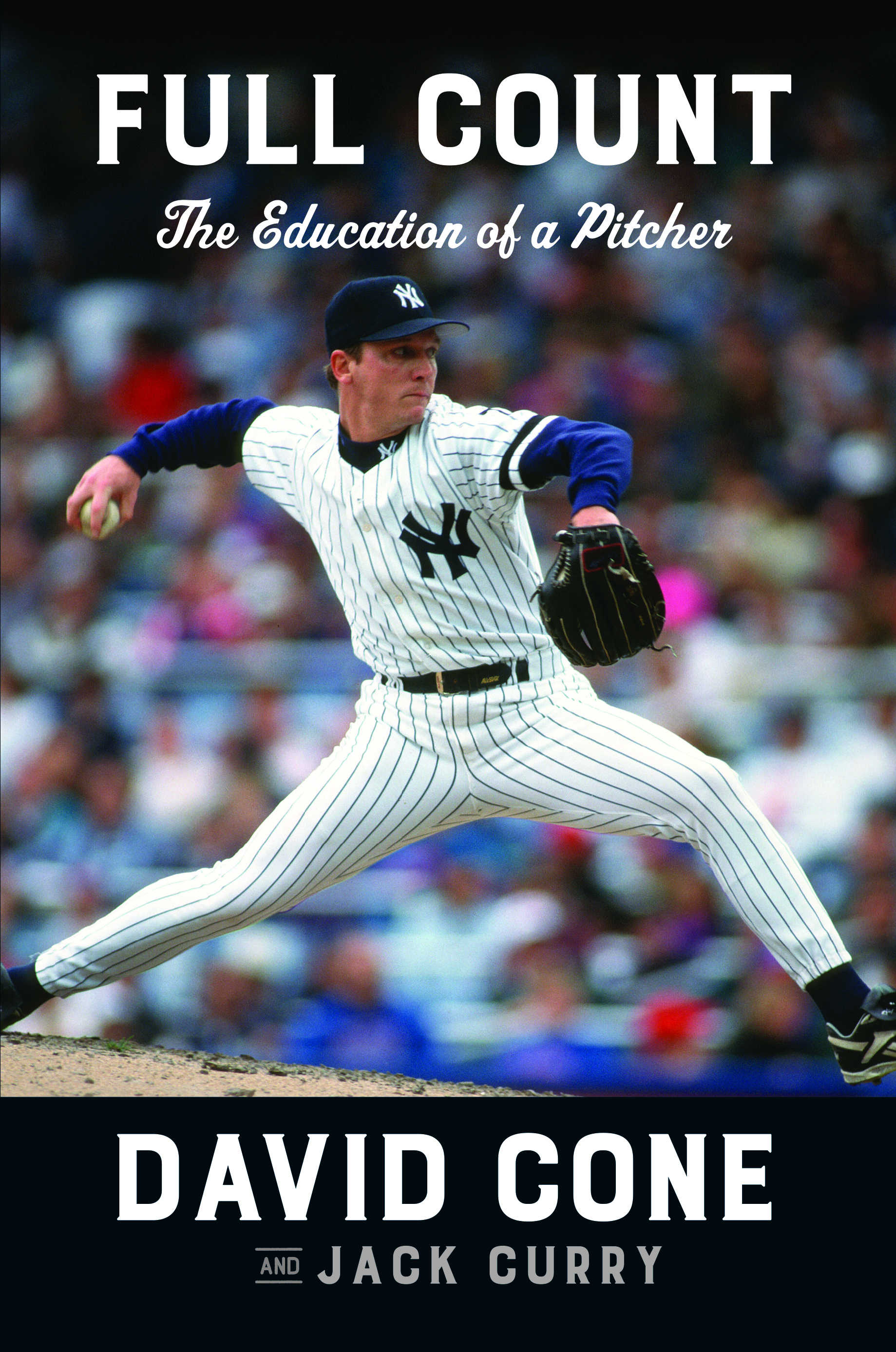

Full Count

The Education of a Pitcher

Contributors

By David Cone

With Jack Curry

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 14, 2019

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538748824

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 14, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Met and Yankee All-Star pitcher David Cone shares lessons from the World Series and beyond in this essential New York Times bestselling memoir for baseball fans everywhere.

“There was a sense about him and an aura about him. Even when he was in trouble, he carried himself like a pitcher who said, ‘I’m the man out here.’ And he usually was.” — Andy Pettitte on David Cone.

To any baseball fan, David Cone was a bold and brilliant pitcher. During his 17-year career, he became a master of the mechanics and mental toughness a pitcher needs to succeed in the major leagues. A five-time All-Star and five-time World Champion now gives his full count — balls and strikes, errors and outs — of his colorful life in baseball.

From the pitchers he studied to the hitters who infuriated him, Full Count takes readers inside the mind of a thoughtful pitcher, detailing Cone’s passion, composure and strategies. The book is also filled with never-before-told stories from the memorable teams Cone played on — ranging from the infamous late ’80s Mets to the Yankee dynasty of the ’90s. And, along the way, Full Count offers the lessons baseball taught Cone — from his mistakes as a young and naive pitcher to outwitting the best hitters in the world — one pitch at a time.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use