By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

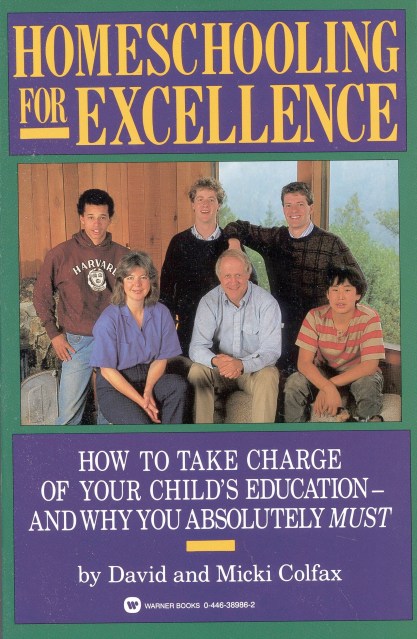

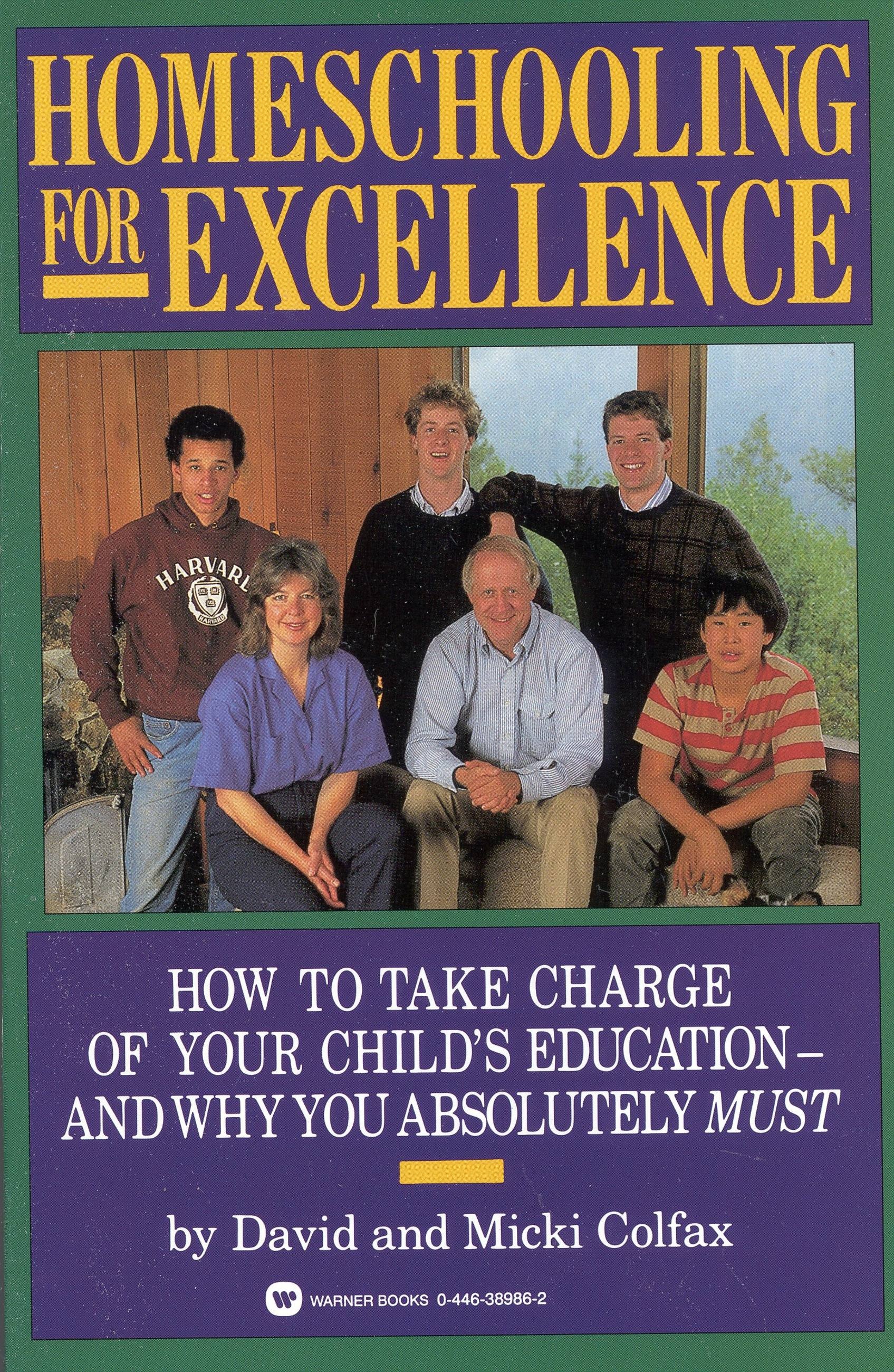

Homeschooling for Excellence

Contributors

By David Colfax

By Micki Colfax

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 1, 1988

- Page Count

- 176 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780446389860

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $11.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 1, 1988. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

THE COLFAXES DIDN’T START TEACHING THEIR BOYS AT HOME TO GET THEM INTO HARVARD – BUT THAT’S WHAT HOMESCHOOLING ACCOMPLISHED!

For over fifteen years, David and Micki Colfax educated their children at home. They don’t think of themselves as pioneers, though that’s what they became. Unhappy with the public schools, the Colfaxes wanted the best education possible for their four sons: a program for learning that met the evolving needs of each child and gave them complete control of how and what their children learned. The results? A prescription for excellence-Harvard educations for their sons Grant, Drew, and Reed. (Their fourth son is still too young for college.)

Now the Colfaxes tell how all parents can become involved in homeschooling. In a straight-talking book that reads like a frank conversation among friends, they tell what they did and how they did it: their educational approaches, the lessons they learned, and what materials-books, equipment, educational aids-proved most useful over the years. Best of all, they show you how you can take charge of your children’s education-in an invaluable sourcebook that will help you find a rewarding and successful alternative to our failing schools.

For over fifteen years, David and Micki Colfax educated their children at home. They don’t think of themselves as pioneers, though that’s what they became. Unhappy with the public schools, the Colfaxes wanted the best education possible for their four sons: a program for learning that met the evolving needs of each child and gave them complete control of how and what their children learned. The results? A prescription for excellence-Harvard educations for their sons Grant, Drew, and Reed. (Their fourth son is still too young for college.)

Now the Colfaxes tell how all parents can become involved in homeschooling. In a straight-talking book that reads like a frank conversation among friends, they tell what they did and how they did it: their educational approaches, the lessons they learned, and what materials-books, equipment, educational aids-proved most useful over the years. Best of all, they show you how you can take charge of your children’s education-in an invaluable sourcebook that will help you find a rewarding and successful alternative to our failing schools.

Genre:

-

"THE CALIFORNIA COLFAXES TEACH THEIR CHILDREN WELL."Newsweek

-

"THEIR EFFORTS TO TEACH THEIR CHILDREN THEMSELVES HAVE BEEN SUCCESSFUL BEYOND MOST PARENTS' DREAMS....Lively and clearly written, Homeschooling for Excellence provides a step-by-step guide...and will make most parents think harder about encouraging their children's interest in learning."Chicago Tribune

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use