By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

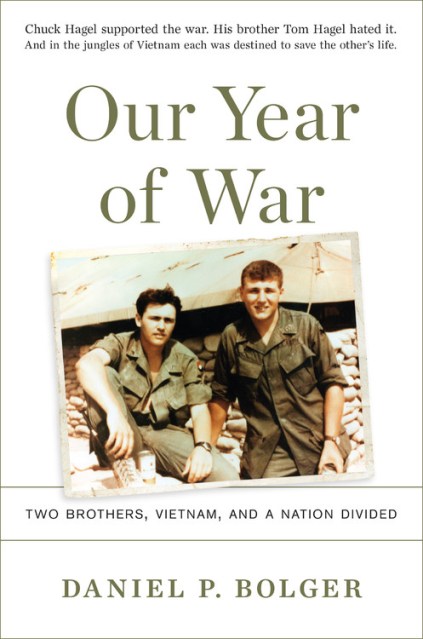

Our Year of War

Two Brothers, Vietnam, and a Nation Divided

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 7, 2017

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306903267

Price

$28.00Price

$36.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 7, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

1968. America was divided. Flag-draped caskets came home by the thousands. Riots ravaged our cities. Assassins shot our political leaders. Black fought white, young fought old, fathers fought sons. And it was the year that two brothers from Nebraska went to war.

In Vietnam, Chuck and Tom Hagel served side by side in the same rifle platoon. Together they fought in the Mekong Delta, battled snipers in Saigon, chased the enemy through the jungle, and each saved the other’s life under fire. But when their one-year tour was over, these two brothers came home side-by-side but no longer in step — one supporting the war, the other hating it.

Former Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel and his brother Tom epitomized the best, and withstood the worst, of the most tumultuous, shocking, and consequential year in the last half-century. Following the brothers’ paths from the prairie heartland through a war on the far side of the world and back to a divided America, Our Year of War tells the story of two brothers at war — a gritty, poignant, and resonant story of a family and a nation divided yet still united.

-

"Our Year of War is the remarkable tale of two brothers--one of them a future Secretary of Defense--who walked point together in the same Army infantry platoon in Vietnam. It's a story of war, and a story of family, and a reminder that America's wars are, in the end, fought by families. Dan Bolger has done us all a great service with this wonderful book."--Nathaniel Fick, author of the New York Times bestseller One Bullet Away

-

"Our Year of War is a vivid war story that soars beyond the battlefields to become a metaphor for life's struggles and redemption. Drawing on an exhaustive depth of research and first-hand combat experience, General Bolger weaves together a tale of brotherly devotion and a warning about ambitious senior officials who lacked humility and common sense."--Bing West, author of The Wrong War: A History of the War in Afghanistan

-

"Daniel Bolger is an unusual general--a fine writer and a masterful storyteller. Here he tells the moving tale of two soldiers, of the US Army (an organization he understands to his bones), of America, and of war. Reading this book is like sitting around the campfire with a tribal elder."--Thomas E. Ricks, bestselling author of Fiasco, The Generals, and Churchill and Orwell

-

"A crisp account of a messy war...Bolger, who won five Bronze Stars during his Army career, brings a unique perspective to the story, as he understands the intricacies of modern warfare and also acknowledges the wide gap between those who fight these wars and those who lead them...Bolger ably conveys how Vietnam felt to those who fought it and what it meant."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Bolger's story of the two Hagel brothers shows how even close family members became alienated from each other by the war in Vietnam."Publishers Weekly

-

"The raw description of a soldier's life will appeal to readers of military history...For readers interested in a new perspective of Vietnam."Library Journal

-

"Engrossing."New York Post

-

"An intimate look at the Vietnam War through the experiences of two brothers who survived it."WTBF Radio

-

"Bolger does a masterful job of researching and referencing...He also captures and explains GI slang from the war."Washington Independent Review of Books

-

"A compelling [story] and one that Bolger tells well."The VVA Veteran

-

"The siblings' story, a part of the American fabric that Bolger weaves deftly, sucks you in."Military Times

-

"A unique true-life story focusing on the 1968 Vietnam war experience of two brothers...[A] captivating, expertly researched, and thoroughly immersive saga. A vivid glimpse into the tumultuous past, a divided America, and the sweltering jungles of war-torn Vietnam, Our Year of War is highly recommended for public and college library military shelves and personal reading lists."Midwest Book Review

-

"The story of two brothers fighting an implacable enemy in a faraway place that just a few years earlier most Americans couldn't find on a map...[Bolger] has experienced war firsthand and is uniquely qualified to tell the Hagels' story. And he pulls no punches. He puts things in perspective. He does an excellent job describing what the Hagels experienced in Vietnam and what was simultaneously happening on the homefront. He provides insight into what senior military leadership was thinking and how it affected soldiers in the jungle."ARMY magazine

-

"A story of the [Hagel] brothers' respective year-long experiences in the U.S. Army during the turbulent Vietnam War and how they came to their individual perspectives regarding that conflict...[Bolger] has weaved a highly readable account of the brothers' lives and war experiences along with the political, military, social, and cultural circumstances extant in the United States, and internationally, at the time...a quickly and easily read book that tells the Hagels' personal story while incorporating the big picture of events and influences from the pivotal year of 1968."New York Journal of Books

-

"A multilayered, nuanced, extensively researched and wonderfully written account of what transpired on the battlefields of Vietnam and on the American homefront during the pivotal year for the war and for our country-1968...Bolger's superbly imagined and expertly presented narrative is much more than simply the story of two brothers who went to war...Bolger provides an insightful examination of the unprecedented domestic political-social upheavals confronting the U.S. in 1968...The best book in many years on the Vietnam War. This is a must-read book."-Vietnam Magazine

-

"A eulogy to lost American values and a clarion for the vanishing virtues of civility and genuine patriotism...A brilliant, exciting and tragic survey...As a war story its hair-raising suspense is as artfully crafted as any spellbinding fiction...[A] sanguine and gritty book that relates history even as it resonates today's real news."Washington Times

-

"Bolger offers an affecting account of Chuck Hagel (who later became secretary of defense) and his brother Tom as they fought-and in some ways continue to refight-their shared tour in Vietnam."The Christian Century

-

"Bolger goes beyond the standard chronological account of soldiers in combat...The book is an excellent look at not only how two brothers coped with war, but also how the U.S. changed with the brothers as the Vietnam War dragged on."Collected Miscellany

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use