Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

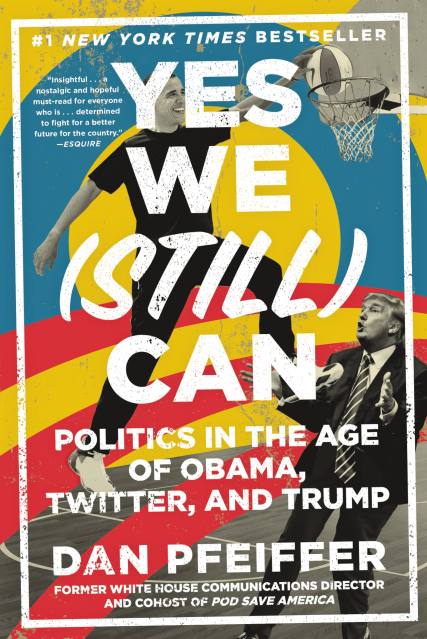

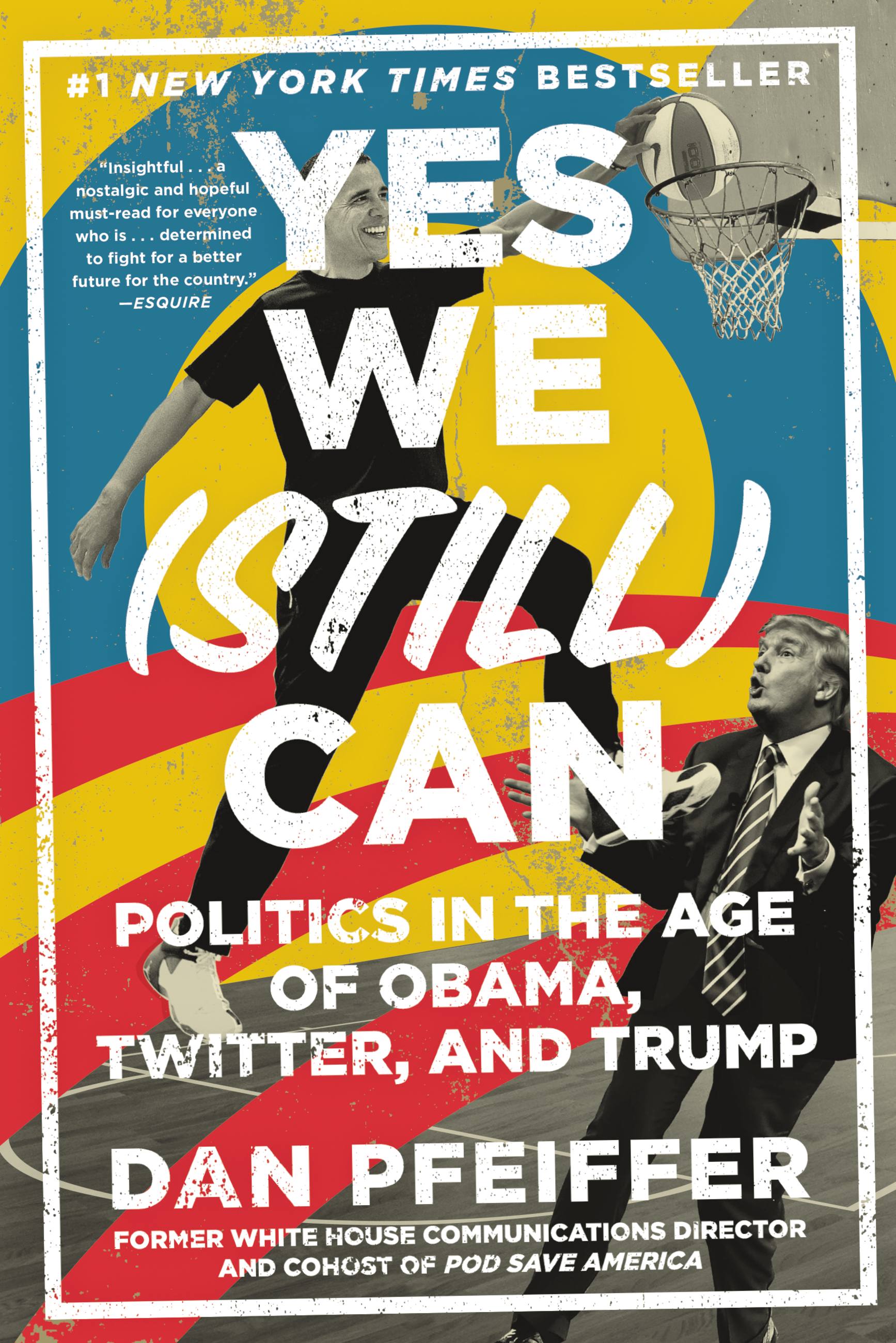

Yes We (Still) Can

Politics in the Age of Obama, Twitter, and Trump

Contributors

By Dan Pfeiffer

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.49 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 19, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

From Obama’s former communications director and current co-host of Pod Save America comes a colorful account of how politics, the media, and the Internet changed during the Obama presidency and how Democrats can fight back in the Trump era.

On November 9th, 2016, Dan Pfeiffer woke up like most of the world wondering WTF just happened. How had Donald Trump won the White House? How was it that a decent and thoughtful president had been succeeded by a buffoonish reality star, and what do we do now?

Instead of throwing away his phone and moving to another country (which were his first and second thoughts), Pfeiffer decided to tell this surreal story, recounting how Barack Obama navigated the insane political forces that created Trump, explaining why everyone got 2016 wrong, and offering a path for where Democrats go from here.

Pfeiffer was one of Obama’s first hires when he decided to run for president, and was at his side through two presidential campaigns and six years in the White House. Using never-before-heard stories and behind-the-scenes anecdotes, Yes We (Still) Can examines how Obama succeeded despite Twitter trolls, Fox News (and their fake news), and a Republican Party that lost its collective mind.

An irreverent, no-BS take on the crazy politics of our time, Yes We (Still) Can is a must-read for everyone who is disturbed by Trump, misses Obama, and is marching, calling, and hoping for a better future for the country.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jun 19, 2018

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781538711729

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use