Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

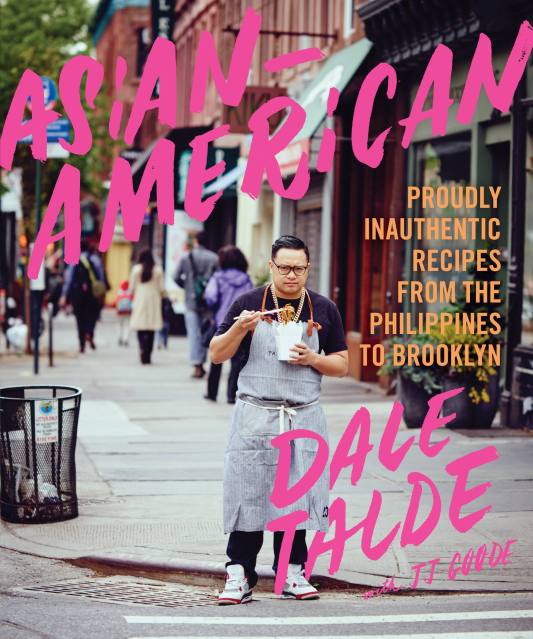

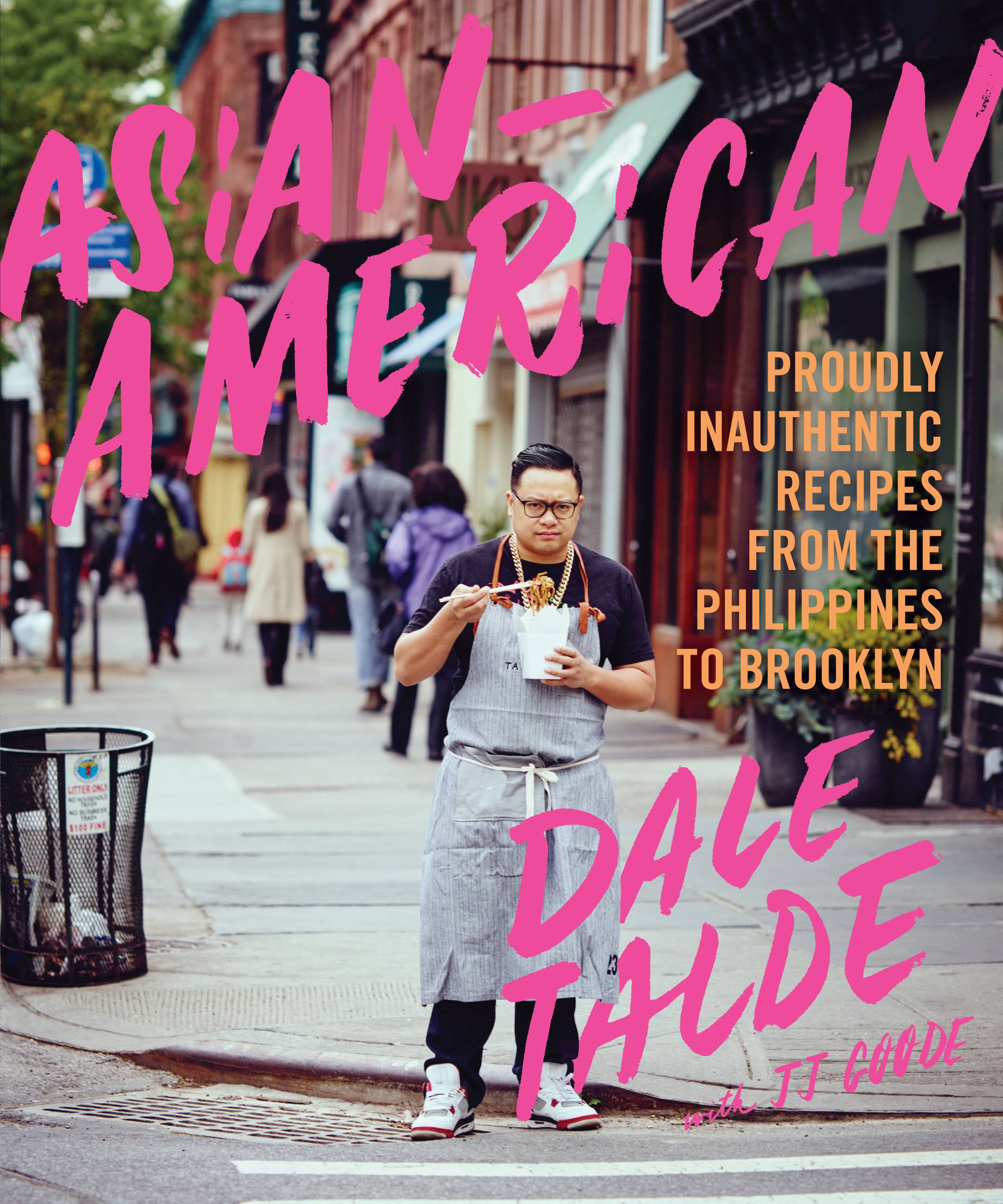

Asian-American

Proudly Inauthentic Recipes from the Philippines to Brooklyn

Contributors

By Dale Talde

With JJ Goode

Formats and Prices

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $13.99 $17.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 15, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Born in Chicago to Filipino parents, Dale Talde grew up both steeped in his family’s culinary heritage and infatuated with American fast food–burgers, chicken nuggets, and Hot Pockets. Today, his dual identity is etched on the menu at Talde, his always-packed Brooklyn restaurant. There he reimagines iconic Asian dishes, imbuing them with Americana while doubling down on the culinary fireworks that made them so popular in the first place. His riff on pad thai features bacon and oysters. He gives juicy pork dumplings the salty, springy exterior of soft pretzels. His food isn’t Asian fusion; it’s Asian-American.

Now, in his first cookbook, Dale shares the recipes that have made him famous, all told in his inimitable voice. Some chefs cook food meant to transport you to Northern Thailand or Sichuan province, to Vietnam or Tokyo. Dale’s food is meant to remind you that you’re home.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 15, 2015

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Life & Style

- ISBN-13

- 9781455585250

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use