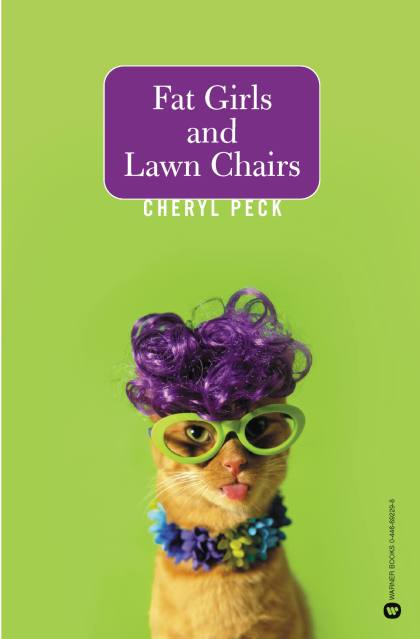

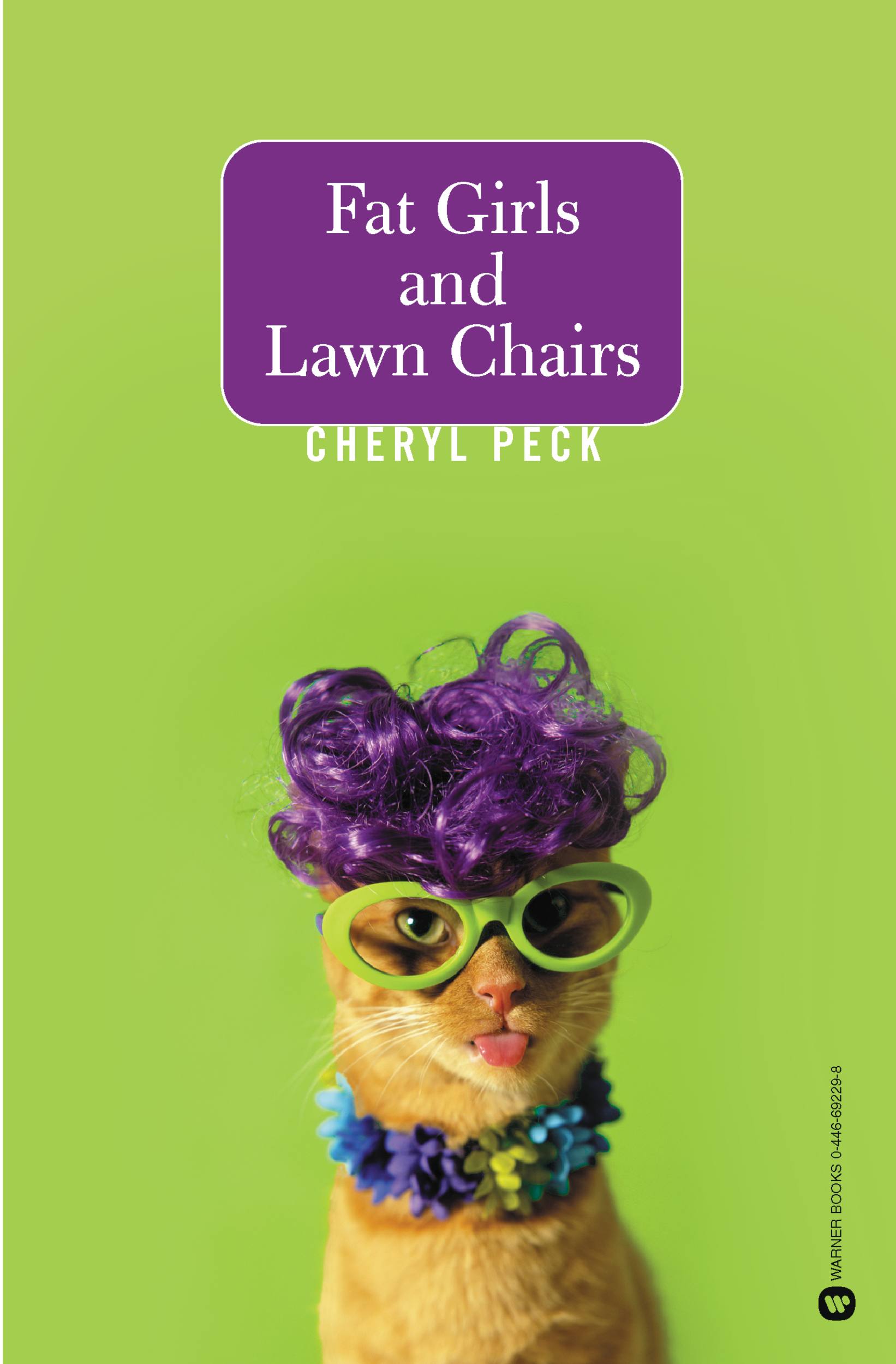

Fat Girls and Lawn Chairs

Contributors

By Cheryl Peck

Formats and Prices

Price

$8.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $8.99 $11.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 1, 2004. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

With self-deprecating humor and compassionate insight, she remembers the time she hit her baby sister in the head with a rock, how her father taught her to swim by throwing her into deep water, and the day when — while weighing in at 300 pounds — she became an inspirational goddess at her local gym.

Filled with universal stories about a daughter’s love for her parents and the eternal quest for finding meaning in it all, this book reveals many seemingly unremarkable moments that make up a life — the weighty events that, like fat girls sitting on lawn chairs, just won’t let go.

- On Sale

- Jan 1, 2004

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780759509856

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use