Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

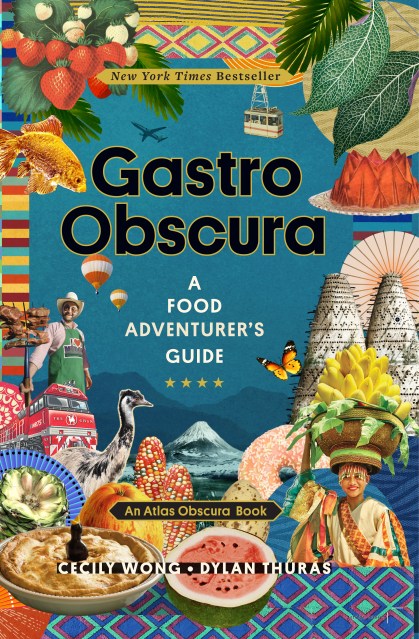

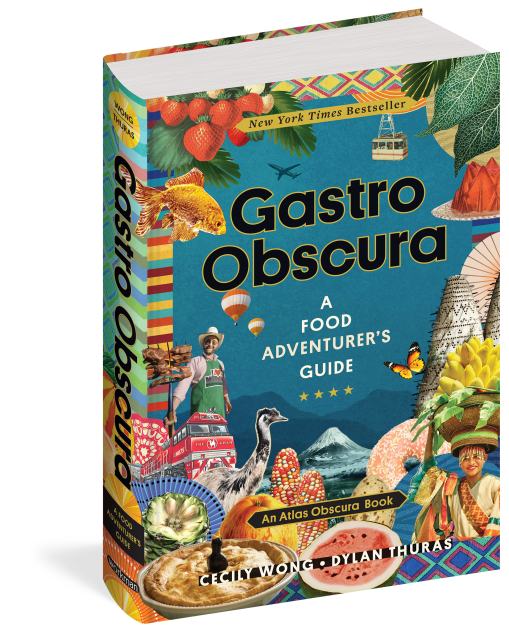

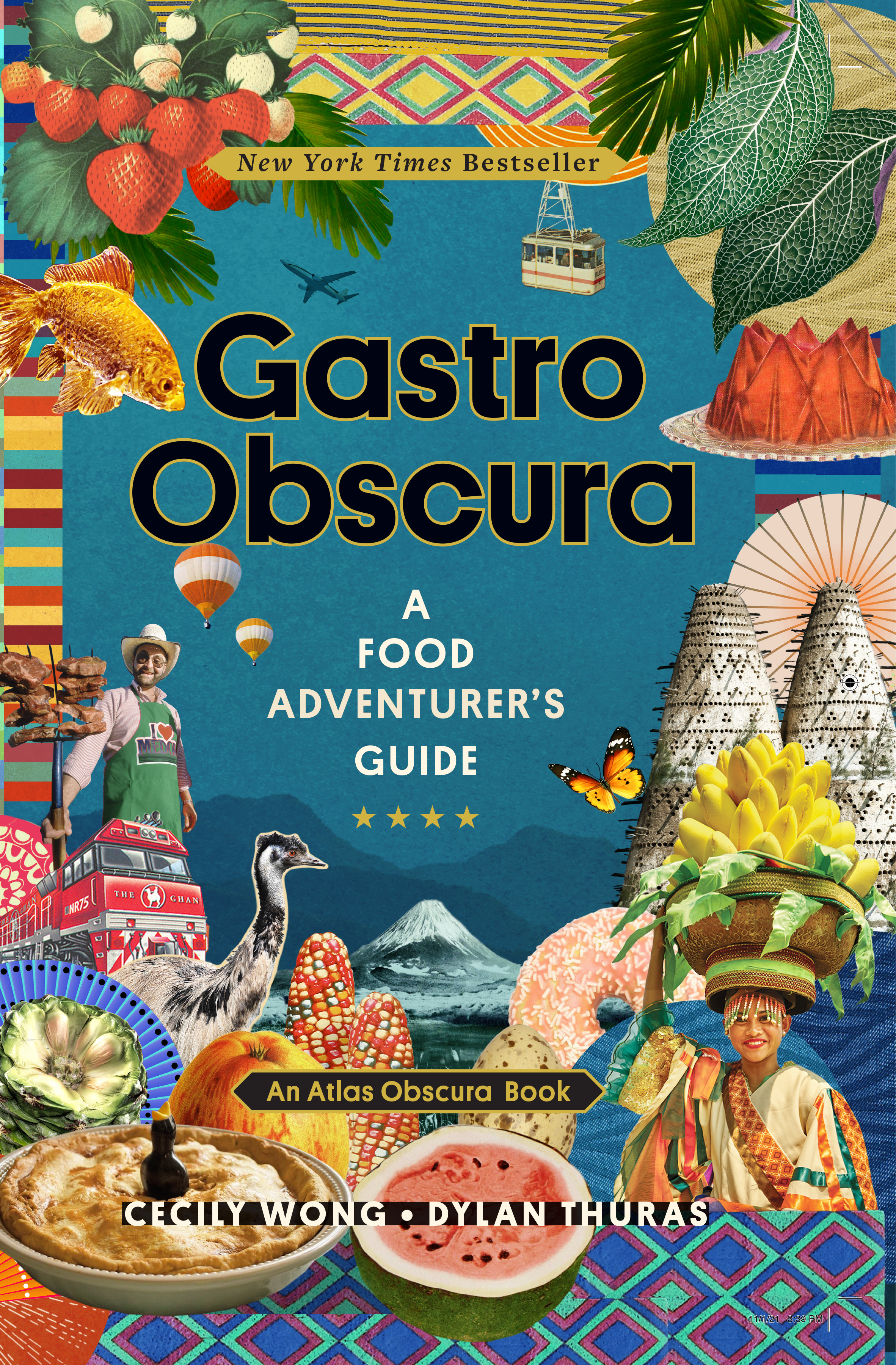

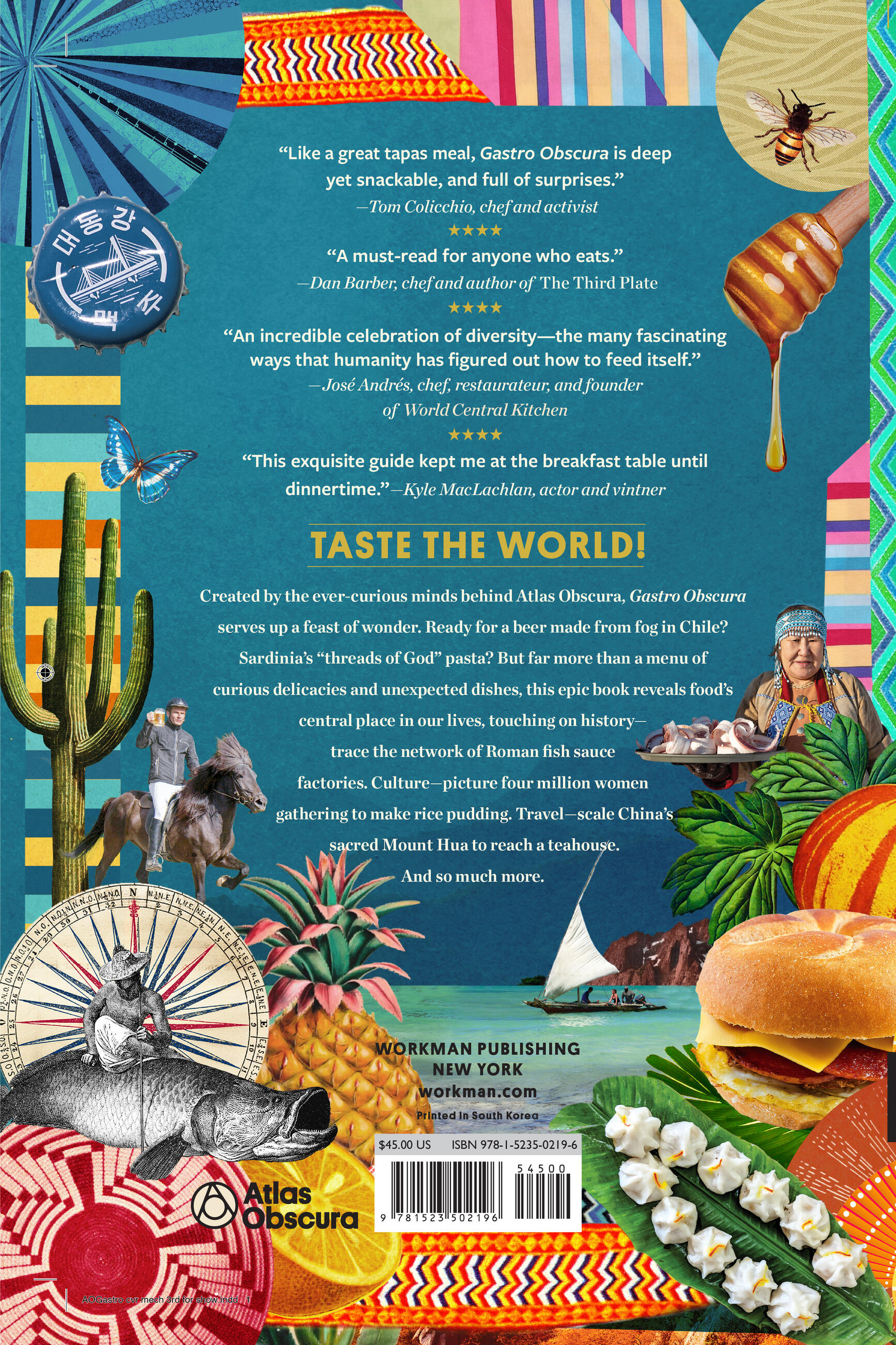

Gastro Obscura

A Food Adventurer's Guide

Contributors

By Cecily Wong

By Dylan Thuras

Formats and Prices

Price

$42.50Price

$53.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $42.50 $53.95 CAD

- ebook $30.99 $39.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 12, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A New York Times, USA Today, and national indie bestseller.

A Feast of Wonder!

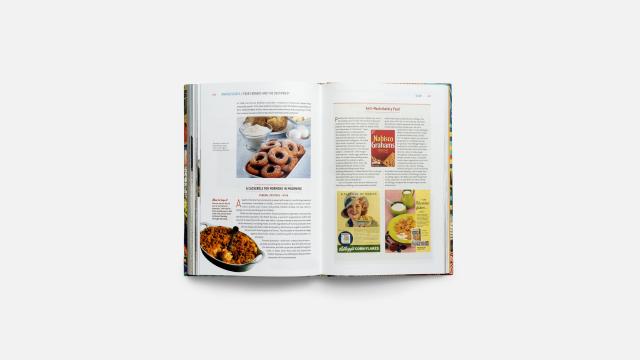

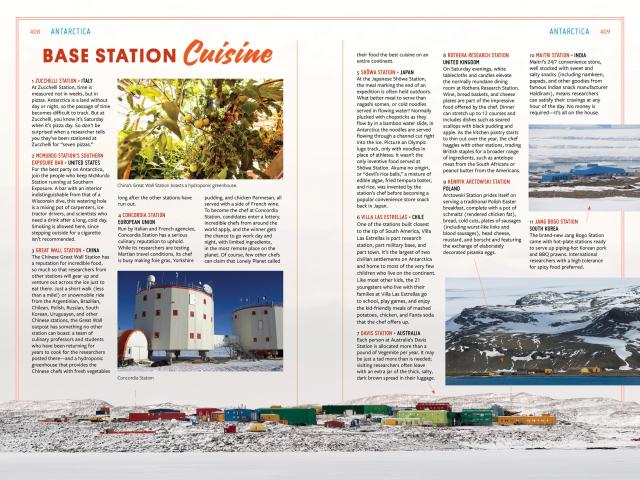

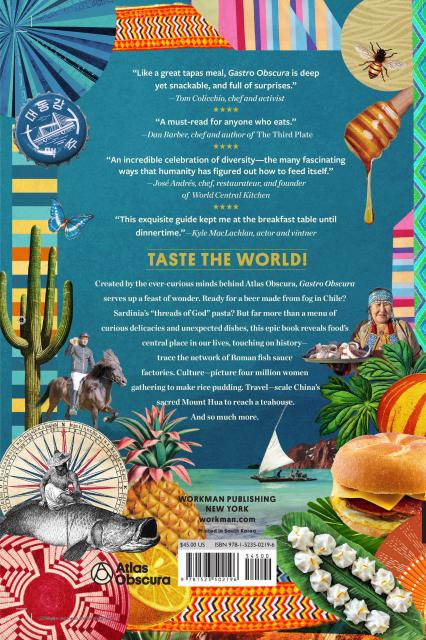

Created by the ever-curious minds behind Atlas Obscura, this breathtaking guide transforms our sense of what people around the world eat and drink. Covering all seven continents, Gastro Obscura serves up a loaded plate of incredible ingredients, food adventures, and edible wonders. Ready for a beer made from fog in Chile? Sardinia’s “Threads of God” pasta? Egypt’s 2000-year-old egg ovens? But far more than a menu of curious minds delicacies and unexpected dishes, Gastro Obscura reveals food’s central place in our lives as well as our bellies, touching on history–trace the network of ancient Roman fish sauce factories. Culture–picture four million women gathering to make rice pudding. Travel–scale China’s sacred Mount Hua to reach a tea house. Festivals–feed wild macaques pyramid of fruit at Thailand’s Monkey Buffet Festival. And hidden gems that might be right around the corner, like the vending machine in Texas dispensing full sized pecan pies. Dig in and feed your sense of wonder.

“Like a great tapas meal, Gastro Obscura is deep yet snackable, and full of surprises. This is the book for anyone interested in eating, adventure and the human condition.” –Tom Colicchio, chef and activist

“This exquisite guide kept me at the breakfast table until dinner time.” –Kyle Maclachlan, actor and vintner

Genre:

-

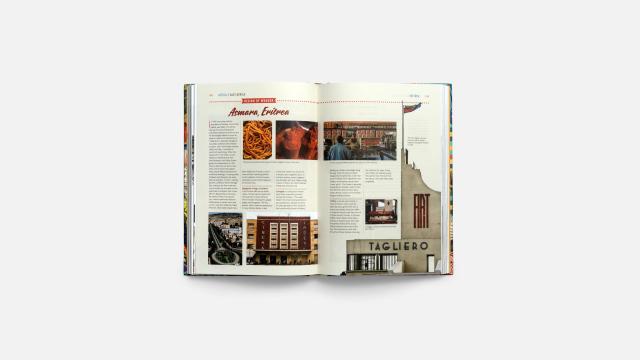

"[Wong and Thuras'] lavishly photographed volume, more eye-opening than mouthwatering, slakes (and often quells) the armchair gourmand’s appetite. Combing 120 nations and all the continents... they have produced a cabinet of culinary curiosities." —The New York Times Book Review

"You cannot help but be drawn to Gastro Obscura.” —The New York Times"There’s so much information in this book. If you love food, the photos are beautiful and for me, it really made me feel like on my couch like I was getting back out there and traveling again. That’s why I love this book. They know what they’re doing. These books are always good, they’re filled with facts, you gotta pick it up.” —bestselling author Isaac Fitzgerald on the TODAY Show

"Dylan Thuras and... Cecily Wong pull together some of the most unique, interesting, and incredible festivals, food and drink, and culinary obscurities from around the globe, transporting the reader into parts unknown—both edible and otherwise."—Smithsonian.com

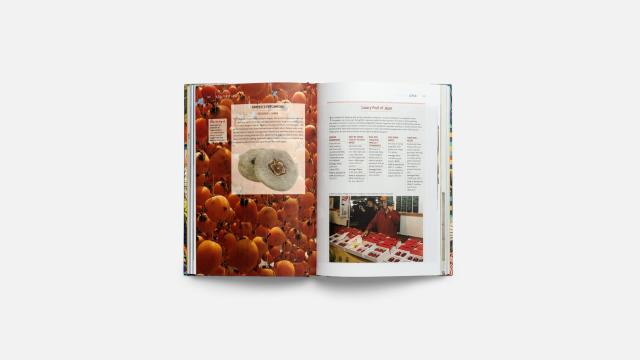

"[A] colorfully illustrated, totally entertaining tour through global cuisine, particularly the quirky sort." — AARP.com

“For the traveler or foodie, this coffee table book can transport them around the world with wonderful stories and photos that will leave their stomachs grumbling—all without ever leaving the couch.” —Food 52 "[A]n enticing read for anyone who is curious about the world. Like a five-star hotel’s platter-stacked buffet artfully arranged to please the eye and palate, Gastro Obscura stimulates aplenty, with hundreds of rich morsels to peruse and savor." —Forbes.com

"An incredible celebration of diversity in food" —Wine Enthusiast

"[An] encyclopedic odyssey... This compendium is a must-have." —Publishers Weekly, starred review

"[Gastro Obscura is a] hard-to-put-down book... Pick a region, pick a page—you can’t go wrong. Armchair travelers and foodies will be left hungry, nostalgic, more knowledgeable about dishes from all over, and, most importantly, ready to try something different, whether it’s found around the corner or across the world."—Library Journal

"Irresistible." —Booklist "A tome to be savored" - Foreward Reviews"[A] casual and fun and yet intelligent treatment of what essentially is a food encyclopedia on the world and its cuisines." —Nik Sharma, author of The Flavor Equation

"This captivating book celebrates the incredible global diversity of food, ingredients, and cooking practices. What could be more important in this moment in time than to be so delightfully engaged in the many ways food cultivates—through sometimes eccentric means!—a profound sense of togetherness.” —Alice Waters, chef and author of We Are What We Eat: A Slow Food Manifesto

“An ambitious, exciting, and zany anthology of heritage foodways, Gastro Obscura tells the stories no one else is telling. In creating a magnum opus that manages to be simultaneously daring as well as fundamentally delicious, this is a culinary high-wire act of culinary anthropology that delivers on its promise and then some. A must-read for anyone who eats.” —Dan Barber, chef and author of The Third Plate

“This book is an incredible celebration of diversity – the many fascinating ways that humanity has figured out how to feed itself. To me, it is really about preservation, the power and importance of remembering old customs and local traditions in order to help us better understand our world today … and into the future.” —José Andrés, chef, restaurateur, and founder of World Central Kitchen

“Like a great tapas meal, Gastro Obscura is deep yet snackable, and full of surprises. In these pages, you'll find riveting stories of human culture ancient and present, history, climate, mythology, commerce and geography -- all through the lens of that thing you thought you already knew: food. This is the book for anyone interested in eating, adventure and the human condition.” —Tom Colicchio, chef and activist

“Thumbing through this exquisite guide kept me at the breakfast table until dinner time.” —Kyle Maclachlan, actor and vintner

- On Sale

- Oct 12, 2021

- Page Count

- 448 pages

- Publisher

- Workman Publishing Company

- ISBN-13

- 9781523502196

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use