By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

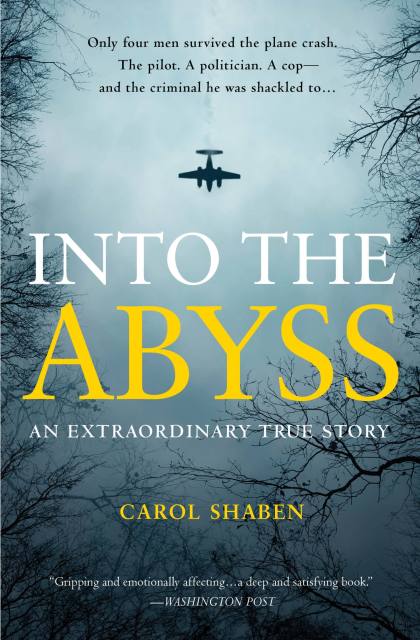

Into the Abyss

An Extraordinary True Story

Contributors

By Carol Shaben

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 21, 2013

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781455545629

Price

$10.99Format

Format:

- ebook $10.99

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $17.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 21, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Read the “gripping and emotionally affecting” book where four men survived the plane crash. The pilot. A politician. A cop… and the criminal he was shackled to (Washington Post).

On an icy night in October 1984, a commuter plane carrying nine passengers crashed in the remote wilderness of northern Alberta, killing six people. Four survived: the rookie pilot, a prominent politician, a cop, and the criminal he was escorting to face charges. Despite the poor weather, Erik Vogel, the 24-year-old pilot, was under intense pressure to fly. Larry Shaben, the author’s father and Canada’s first Muslim Cabinet Minister, was commuting home after a busy week at the Alberta Legislature. Constable Scott Deschamps was escorting Paul Archambault, a drifter wanted on an outstanding warrant. Against regulations, Archambault’s handcuffs were removed-a decision that would profoundly impact the men’s survival.

As the men fight through the night to stay alive, the dividing lines of power, wealth, and status are erased, and each man is forced to confront the precious and limited nature of his existence.

-

"Gripping and emotionally affecting. . . a deep and satisfying book."Washington Post

-

"[Shaben] vividly recreates how these four total strangers managed to survive the tragedy."New York Post

-

"With Into the Abyss Carol Shaben gives us an astonishing true story of catastrophe and redemption. Shaben writes from the inside out, as in the best non-fiction, creating a nuanced and tightly braided portrait of four men and their shared trauma that is by turns terrifying and deeply humane. Every line in this story rings true."John Vaillant, author of The Tiger

-

"Electrifying...Shaben's riveting narrative is filled with heart and the story is well told."Publishers Weekly

-

"[T]his is a complex, chilling narrative rendered with depth and precision, engaged in both its characters and the larger social moment... A worthy addition to the canon of extreme-survival nonfiction."Kirkus

-

"As a concept, it doesn't get much better [than this]... Into the Abyss is in the best traditions of true-life journalism and grips from beginning to end."Iain Finlayson, The Times

-

"The gripping account . . . is ultimately about the survivors, telling the story in scouring yet respectful detail of the four men who limped away from the fatal crash."Fish Griwkowsky, Edmonton Journal

-

"A story that has haunted Vancouver-based writer Carol Shaben, Larry's daughter, since it happened... She was able to use [Archambault's] story to take readers along on that stormy night, to the side of a mountain where four men struggled to stay alive overnight alongside the six others who had died."Tracy Sherlock, Vancouver Sun

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use