By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

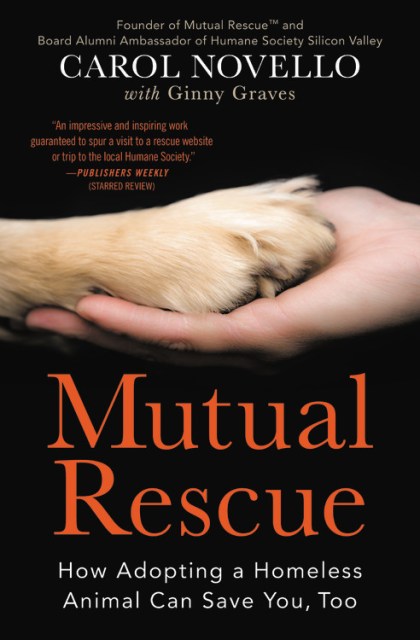

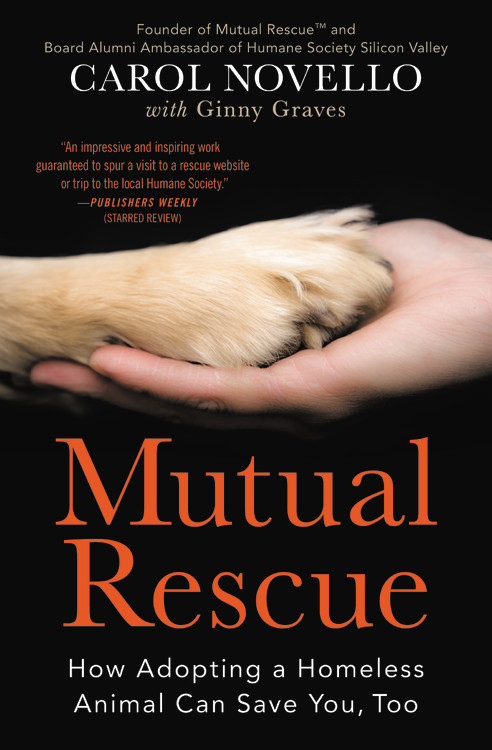

Mutual Rescue

How Adopting a Homeless Animal Can Save You, Too

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 7, 2020

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538713549

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 7, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A moving and scientific look at the curative powers–both physical and mental–of rescuing a shelter animal, by the president of Humane Society Silicon Valley.

MUTUAL RESCUE profiles the transformational impact that shelter pets have on humans, exploring the emotional, physical, and spiritual gifts that rescued animals provide. It explores through anecdote, observation, and scientific research, the complexity and depth of the role that pets play in our lives. Every story in the book brings an unrecognized benefit of adopting homeless animals to the forefront of the rescue conversation.

In a nation plagued by illnesses–16 million adults suffer from depression, 29 million have diabetes, 8 million in any given year have PTSD, and nearly 40% are obese–rescue pets can help: 60% of doctors said they prescribe pet adoption and a staggering 97% believe that pet ownership provides health benefits. For people in chronic emotional, physical, or spiritual pain, adopting an animal can transform, and even save, their lives.

Each story in the book takes a deep dive into one potent aspect of animal adoption, told through the lens of people’s personal experiences with their rescued pets and the science that backs up the results. This book will resonate with readers hungering for stories of healing and redemption.

MUTUAL RESCUE profiles the transformational impact that shelter pets have on humans, exploring the emotional, physical, and spiritual gifts that rescued animals provide. It explores through anecdote, observation, and scientific research, the complexity and depth of the role that pets play in our lives. Every story in the book brings an unrecognized benefit of adopting homeless animals to the forefront of the rescue conversation.

In a nation plagued by illnesses–16 million adults suffer from depression, 29 million have diabetes, 8 million in any given year have PTSD, and nearly 40% are obese–rescue pets can help: 60% of doctors said they prescribe pet adoption and a staggering 97% believe that pet ownership provides health benefits. For people in chronic emotional, physical, or spiritual pain, adopting an animal can transform, and even save, their lives.

Each story in the book takes a deep dive into one potent aspect of animal adoption, told through the lens of people’s personal experiences with their rescued pets and the science that backs up the results. This book will resonate with readers hungering for stories of healing and redemption.

Genre:

-

"The premise put forward by Novello, president of Humane Society Silicon Valley, in her first book is a simple one: rescuing a pet from a shelter helps both the animal and the owner in numerous ways. This collection of anecdotes, bolstered by the requisite statistics and studies, proves her point time and again. Novello opens with the story of how two Parkland School shooting survivors found solace in a pair of rescue dogs, one a mini Australian shepherd trained as a therapy animal, the other a puppy (of an unspecified breed) recently rescued from an abusive home; both were powerfully effective in helping their owners recuperate from trauma. While not all of Novello's accounts are this dramatic, they're equally impactful, variously showing how animals can help owners overcome the loss of a child or the suicide of a loved one, combat mental illness, adopt a healthier lifestyle, and even enhance a child's cognitive and emotional development. A selection of resources, such as volunteering tips for people unable to commit to pet ownership, rounds out the book. It's an impressive and inspiring work guaranteed to spur a visit to a rescue web site or trip to the local Humane Society."Publisher's Weekly, Starred Review

-

"Blending emotional appeal with scientific evidence, Novello presents a sound basis for the community benefits of rescuing shelter animals and supporting animal welfare organizations."--Library Journal

-

"Adopting a pet can greatly benefit the lives of people who are emotionally hurting. Read these heartwarming stories in Mutual Rescue."Temple Grandin, PhD, author ofAnimals in Translation and Animals Make Us Human

-

"Through authentic accounts, scientific evidence, and personal narrative, Carol Novello illustrates how when we rescue a homeless animal, we ourselves are so often rescued right back! This book is destined to save lives."Marty Becker, DVM, and Jack Canfield, #1 New York Times bestselling coauthors of Chicken Soup for the Pet Lover's Soul

-

"Packed with heartrending stories of struggling people who have adopted homeless animals, this fascinating book reveals the many unrecognized ways dogs and cats can ground us, provide a sense of purpose, and give us the strength to move forward. Part science, part story, Mutual Rescue is all heart. It made me cry and filled me with hope for our planet and every person on it."Mallika Chopra, author of Living with Intent: My Somewhat Messy Journey to Purpose, Peace, and Joy

-

"I love Mutual Rescue's films, so when I heard about this new book, I raced to read it. The stories about rescued pets rescuing people were like rays of bright sunshine on a stormy afternoon. Truly an awe-inspiring book!"Marci Shimoff, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Happy for No Reason and Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul

-

"Mutual Rescue juxtaposes authentic stories and scientific thought about the animal-human bond. It touches hearts, opens minds, and inspires compassion-a life-changing book."Brian Hare, founder of Duke Canine Cognition Center and New York Times bestselling author of The Genius of Dogs

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use