By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

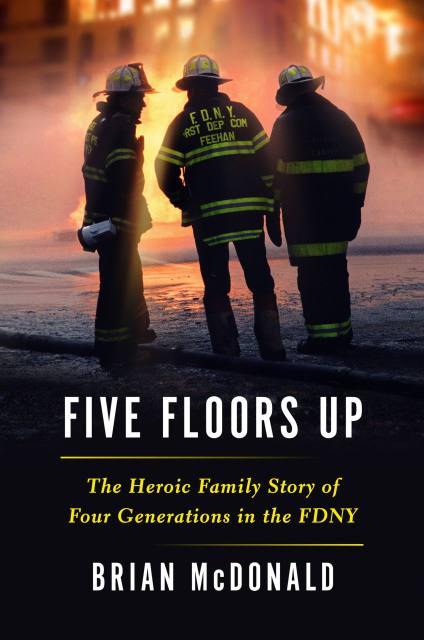

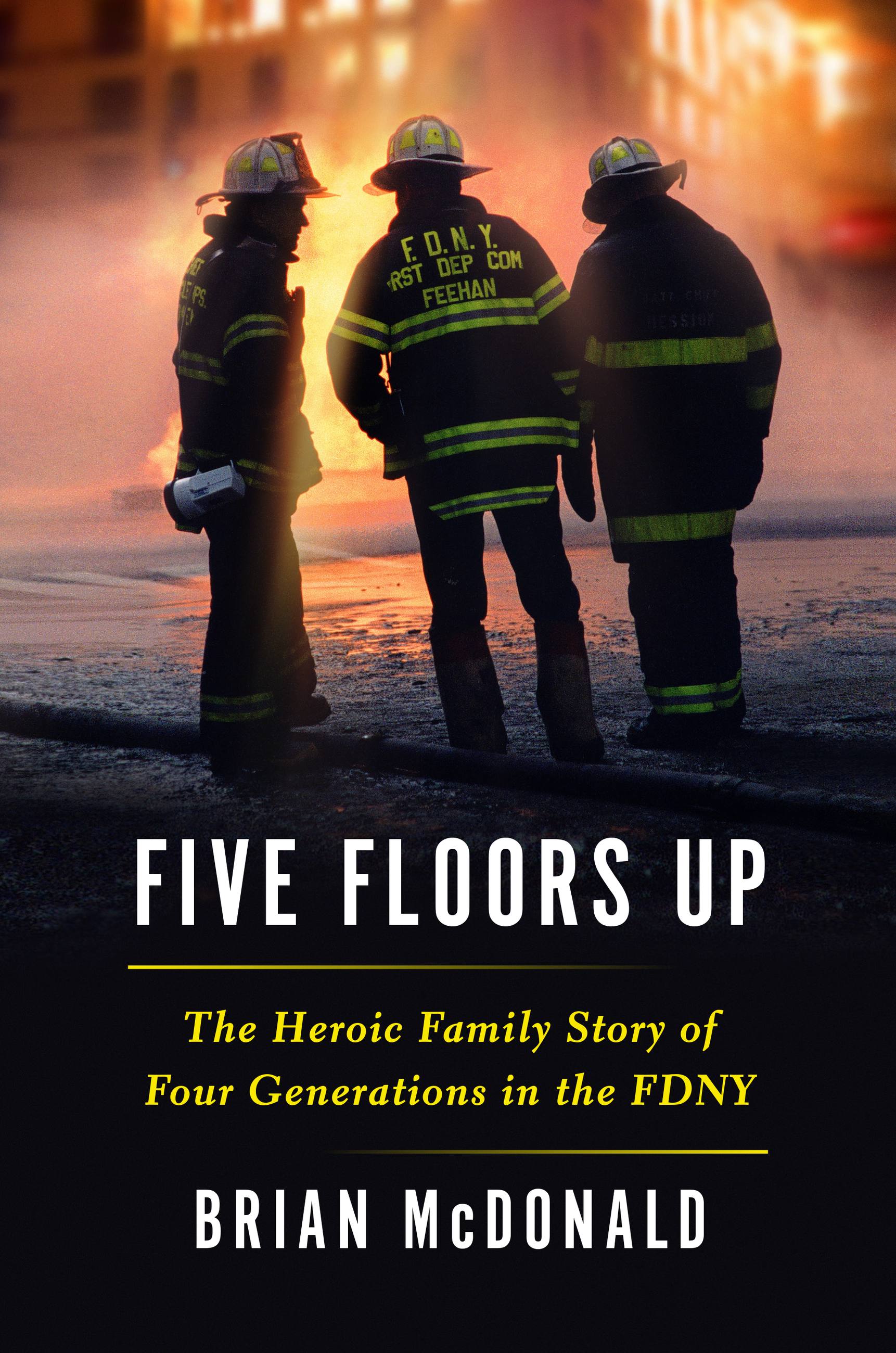

Five Floors Up

The Heroic Family Story of Four Generations in the FDNY

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 6, 2022

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538753200

Price

$29.00Price

$37.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 6, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Seen through the eyes of four generations of a firefighter family, Five Floors Up the story of the modern New York City Fire Department. From the days just after the horse-drawn firetruck, to the devastation of the 1970s when the Bronx was Burning, to the unspeakable tragedy of 9/11, to the culture-busting department of today, a Feehan has worn the shoulder patch of the FDNY. The tale shines the spotlight on the career of William M. Feehan. “Chief” Feehan is the only person to have held every rank in the FDNY including New York City’s 28th Fire Commissioner. He died in the September 11, 2001 attack on the World Trade Center. But Five Floors Up is at root an intimate look at a firefighter clan, the selflessness and bravery of not only those who face the flames, but the family members who stand by their sides. Alternately humorous and harrowing, rich with anecdotes and meticulously researched and reported, Five Floors Up takes us inside a world few truly understand, documenting an era that is quickly passing us by.

-

“Five Floors Up is an homage to the families who absorb the aftermath of such courageous choices and a tribute to those whose job is much more than a career. It is a resurrection of firefighters fallen in battle with the “red devil” and a celebration of those who have picked up the hose in their stead.”Wall Street Journal

-

"McDonald tells the story of a four-generation FDNY family, the department they serve, and the bonds that inspired their devotion to what they see as a calling, a duty and a way of life."New York Post

-

“Five Floors Up takes us on a heart-pounding journey of ordinary heroes, running into extreme fires to rescue those trapped while their families fear for their safety. We see the courageous lives of multiple generations of firefighters and deeply get to know Chief Bill Feehan as a revered leader in the FDNY who was with me in the World Trade Center on 9/11, before it collapsed.”JOSEPH PFEIFER, Assistant Chief FDNY (Ret.), author of the New York Times bestseller Ordinary Heroes: A Memoir of 9/11

-

“Brian McDonald knows New York City, and in Five Floors Up he’s brilliantly given us its history through the eyes of four generations of a firefighter family, including FDNY Chief William Feehan, who died heroically on 9/11. It’s deep, full of fascinating stories, funny, and vividly written.”J.T. MOLLOY, New York Times bestselling coauthor of The Greatest Beer Run Ever

-

"In the great Zinnian tradition of books that tell the histories of times and places (and their attendant social movements) through the tales of ordinary people, Five Floors Up is about firefighting in New York the way Moby-Dick is about whaling, which is to say, down to the last scrupulously observed drop of water, and in some ways not at all. Beyond the vivid, sweeping tale of the family at its heart and the Department they faithfully served for generations, and beyond the riveting account of the events of 9/11 that fixed that Department permanently in the national consciousness, this extraordinarily comprehensive and utterly convincing book is so many histories all at once. It’s a study of the inexorable power of local politics and the competing sway of the Catholic church in New York at the mid-century peak of its parochial schools. It’s a gimlet-eyed view on American manufacturing, corporate life and building development through a catalogue of the notable conflagrations that marked some of those histories' darkest passages. It somehow becomes, through the inventive utility of a deliberately tight focus, a demographic and social history of all New York--its neighborhoods, changing economic fortunes, labor battles, union and electoral politics, social mobility, and civil unrest. It’s a history of race relations in New York in the 20th Century. It’s a fascinating study of the anthropology of civil service and its tribalistic rituals of hiring, advancement, and survival. It’s a portrait of the peculiar, irrational, and selfless bravery it takes to be a firefighter, and of the local cultures that engender and perpetuate that bravery. There are so many reasons to read this terrific book. Read it if you want to understand how New York works. Read it if you want to better grasp the rising, falling, and rising-again fortunes of cities in the second half of the 20th Century. Read it if you want a gripping human drama. Whatever the reason you read it, you'll find in it what you're looking for, and more."MATTHEW THOMAS, New York Times bestselling author of We Are Not Ourselves

-

“When you start reading Brian McDonald’s Five Floors Up, you resent any time you have to put it aside. You see, McDonald is a brilliant weaver of words, and here he’s taken the history of the New York City Fire Department, works his magic, and out comes the story of four generations of the Feehan family. He talks about traditional sexism, prejudice, along with love and the heroism of saving others from certain death. Filled with family stories, and facts too, the soul of New York City is bared for native and outsider alike. Start with a dozen copies to share.”MALACHY MCCOURT, New York Times bestselling author of A Monk Swimming and Death Need Not Be Fatal

-

"A work of great insight and compassion. Brian McDonald burrows deep into the culture of the FDNY, both historically and personally through the family dynamics of the Feehans, a legendary firefighting clan. He pierces the piety that sometimes surrounds this subject and finds moments of simple heroism that will take your breath away. There have been many other books about big city firefighters, but none with this level of drama, humor and understanding. Five Floors Up is a revelation."T.J. ENGLISH, New York Times bestselling author of Dangerous Rhythms and The Westies

-

“McDonald writes with all the vividness of firefighting genre master Dennis Smith, but his story isn’t all hooks and ladders. . . A closely observed study of ordinary heroes and the thousands more like them whose lives are always on the line."Kirkus Reviews

-

“This is a gripping drama of heroic battles with the red devil, the evolution of the FDNY, changes in fire-fighting technologies, the tumultuous politics of the Big Apple, and the culture of its civil servants. McDonald also provides an excellent and moving memorial to Chief Feehan and all the heroes of the September 11, 2001, attack as well as the 1,157 firefighters who have fallen in the line of duty throughout FDNY’s history.”Booklist

-

“Journalist McDonald (Last Call at Elaine’s) surveys the last century of firefighting in New York City through the lens of one family’s captivating history: the Feehans. . . The narrative moves fire-by-fire tamed, addressing changing hiring practices, politics, and firefighting techniques, with due discussion of the FDNY’s history of racism and sexism. It’s a worthy complement to titles like Notes from the Fireground, for readers who enjoy histories with heroes at the forefront.”Publishers Weekly

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use