By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

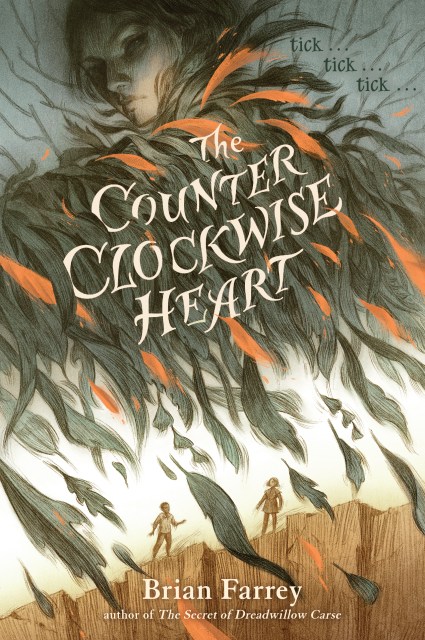

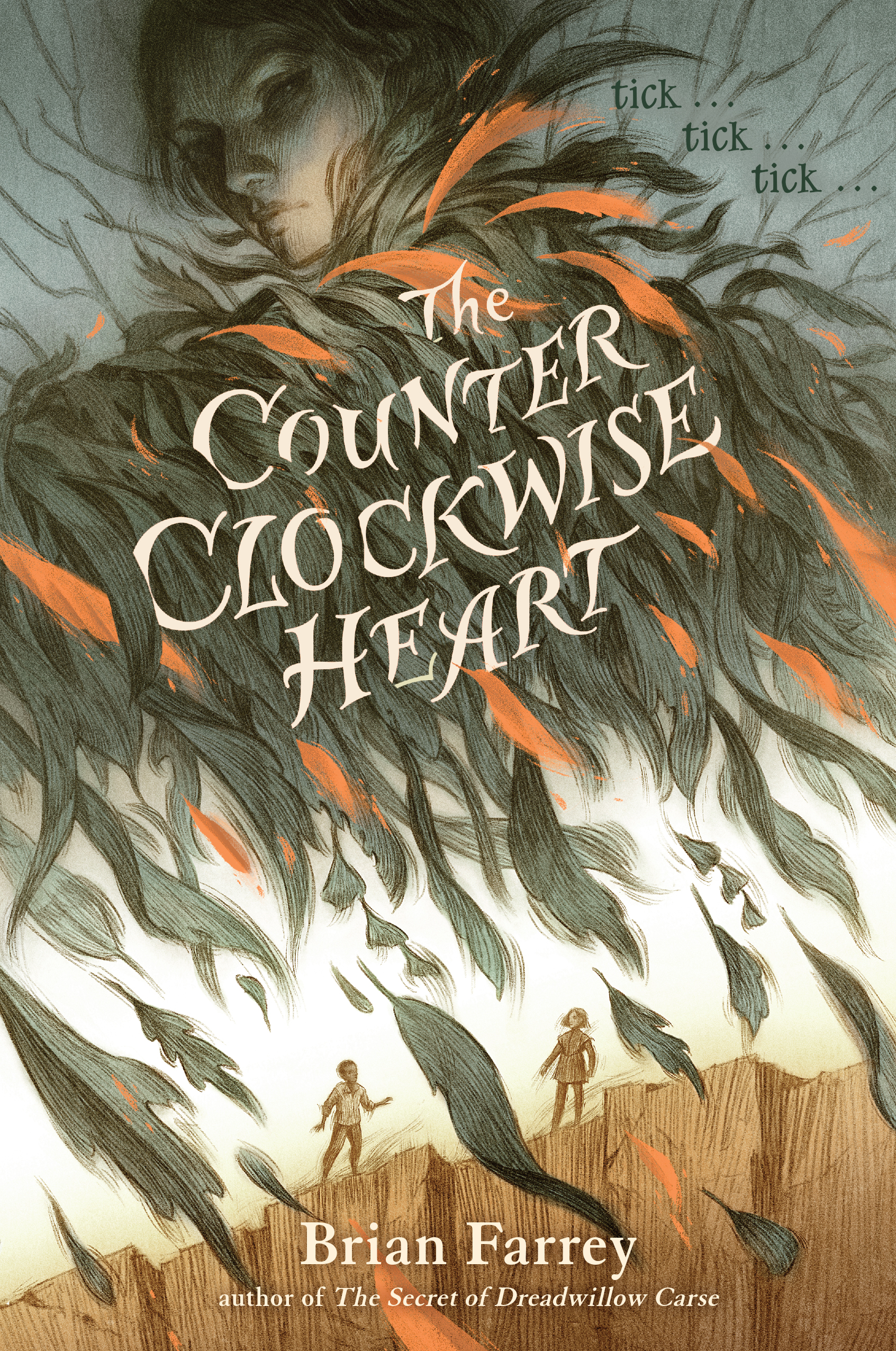

The Counterclockwise Heart

Contributors

By Brian Farrey

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 28, 2023

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9781643753522

Price

$7.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $7.99 $11.99 CAD

- ebook $7.99 $9.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 28, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

WINNER OF THE 2023 MINNESOTA BOOK AWARD FOR MIDDLE GRADE LITERATURE

“Entertaining, fast-paced and thoughtful.”

—The New York Times Book Review

In this thrilling fantasy novel from an award-winning author, a prince and a mage must untangle the riddles from their shared past to save the future of the empire–or risk seeing everything they both love destroyed.

Tick . . . tick . . . tick . . .

Time is running out in the empire of Rheinvelt.

The sudden appearance of a strange and frightening statue foretells darkness. The Hierophants—magic users of the highest order—have fled the land. And the shadowy beasts of the nearby Hinterlands are gathering near the borders, preparing for an attack.

Young Prince Alphonsus is sent by his mother, the Empress Sabine, to reassure the people while she works to quell the threat of war. But Alphonsus has other problems on his mind, including a great secret: He has a clock in his chest where his heart should be—and it’s begun to run backwards, counting down to his unknown fate.

Searching for answers about the clock, Alphonsus meets Esme, a Hierophant girl who has returned to the empire in search of a sorceress known as the Nachtfrau. When riddles from their shared past threaten the future of the empire, Alphonsus and Esme must learn to trust each other and work together to save it—or see the destruction of everything they both love.

-

Booklist “A pleasing mix of fantasy and mystery with compassion at its (ticking) heart.”—The Bulletin for the Center of Children’s Books “Epic…This is a thought-provoking coming-of-age story.” --Kirkus Reviews “Unique…a tale of magic, lies, and sacrifice make a standout read for the middle-grade genre.”—YA Books Central

*Winner of the Minnesota Book Award*

"Farrey conjures a world bristling with spells and secrets. Readers will revel in this gripping, fable-like adventure."

—Stefan Bachmann, author of Cinders Sparrows

"Filled with friendship and magic, mysteries and betrayal, and a race against a ticking clock, this is top-notch fantasy with a heart. I loved it!" —Adam Perry, author of The Thieving Collectors of Fine Children's Books“The Counterclockwise Heart encourages readers to be true to themselves, and to consider the source when confronted with opinions that contradict their own experience. … [an] entertaining, fast-paced and thoughtful novel … wise.”

—The New York Times Book Review“A fascinating fairy tale.”

B>The Minneapolis Star-Tribune, “Books to look forward to in 2022”“Full of drama, twists and turns, and poignant points of view, the novel's storylines converge into an unforgettable ending that will leave readers thinking about the pesky element of time and the role it plays in their lives.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use