Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

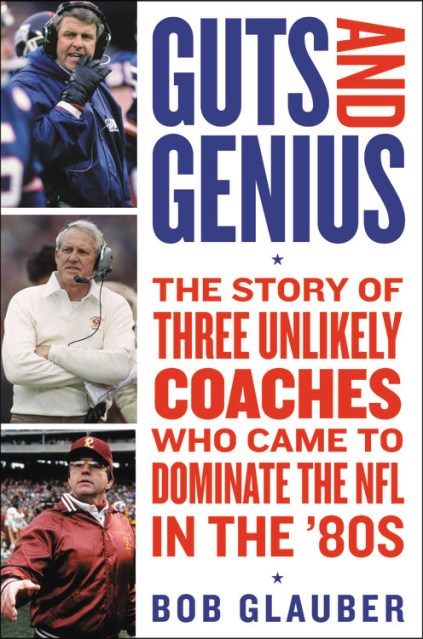

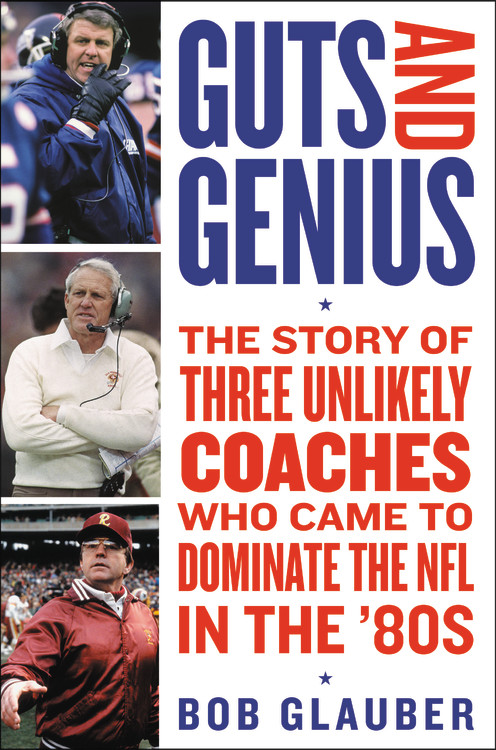

Guts and Genius

The Story of Three Unlikely Coaches Who Came to Dominate the NFL in the '80s

Contributors

By Bob Glauber

Read by Jamie Renell

Formats and Prices

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 20, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

How three football legends — Bill Walsh, Joe Gibbs, and Bill Parcells — won eight Super Bowls during the 1980s and changed football forever.

Bill Walsh, Joe Gibbs and Bill Parcells dominated what may go down as the greatest decade in pro football history, leading their teams to a combined eight championships and developing some of the most gifted players of all time in the process. Walsh, Gibbs and Parcells developed such NFL stars as Joe Montana, Lawrence Taylor, Jerry Rice, Art Monk and Darrell Green. They resurrected the careers of players like John Riggins, Joe Theismann, Doug Williams, Everson Walls and Hacksaw Reynolds. They did so with a combination of guts and genius, built championship teams in their own likeness, and revolutionized pro football like few others. Their influence is still evident in today’s game, with coaches who either worked directly for them or are part of their coaching trees now winning Super Bowls and using strategy the three men devised and perfected. In interviews with more than 150 players, coaches, family members and friends, GUTS AND GENIUS digs into the careers of three men who overcame their own insecurities and doubts to build Hall of Fame legacies that transformed their generation and continue to impact today’s NFL.

Bill Walsh, Joe Gibbs and Bill Parcells dominated what may go down as the greatest decade in pro football history, leading their teams to a combined eight championships and developing some of the most gifted players of all time in the process. Walsh, Gibbs and Parcells developed such NFL stars as Joe Montana, Lawrence Taylor, Jerry Rice, Art Monk and Darrell Green. They resurrected the careers of players like John Riggins, Joe Theismann, Doug Williams, Everson Walls and Hacksaw Reynolds. They did so with a combination of guts and genius, built championship teams in their own likeness, and revolutionized pro football like few others. Their influence is still evident in today’s game, with coaches who either worked directly for them or are part of their coaching trees now winning Super Bowls and using strategy the three men devised and perfected. In interviews with more than 150 players, coaches, family members and friends, GUTS AND GENIUS digs into the careers of three men who overcame their own insecurities and doubts to build Hall of Fame legacies that transformed their generation and continue to impact today’s NFL.

Genre:

-

"Back in the pre-internet days, when football was a big game but not the gigantic one it is today, Bob Glauber and I cut my NFL reporting teeth on the Giants and the great teams of the NFC. I am so glad he wrote Guts and Genius, because sometimes I fear the greatness of the Walsh-Parcells-Gibbs generation hasn't been fully appreciated. Glauber captures the essence of the genius of Walsh, the domineering Parcells, and the wily Gibbs. The vividly told stories of how these three men had a grip on an era of football are valuable not just for football fans but for anyone who seeks greatness in any walk of life. This book is a must for any sporting bookshelf."Peter King, Monday Morning Quarterback and NBC Sports

-

"Bob Glauber, as he usually does, has written a book that takes football fans of all ages inside the lives of three of the most significant figures in the game's history. If you love pro football as I do, you will love this book."Bill Polian, former GM of the Buffalo Bills, Carolina Panthers, and Indianapolis Colts

-

"Fabulous book. One of the best sports books I've ever read. This is the inside story of three of the greatest football coaches of their generation. They knew how to win, and this is the captivating story of how they won -- not just what made headlines, but the little tricks of brilliance no one knew about that made them champions."Ernie Accorsi, former GM of the Baltimore Colts, Cleveland Browns, and New York Giants

-

"Football began to climb to the heights it reached today in the 1980s, in large part thanks to Bill Walsh, Bill Parcells and Joe Gibbs. Bob Glauber perfectly brings together these men, with that time, to give us a glimpse of the greatness behind the guts and genius."Adam Schefter, ESPN NFL reporter and author of The Man I Never Met: A Memoir

-

"Three dominant coaches, three dominant teams, one dominant writer. It's an irresistible combination. Long-time NFL writer Bob Glauber was right there as Bill Walsh, Bill Parcells, and Joe Gibbs created the best three-way rivalry in NFL history, and now he brings incredible insight and perspective to one of the most fascinating eras in NFL history. Walsh, Parcells, and Gibbs combined for three Hall of Fame busts and eight Super Bowl championships, and Glauber takes us behind the scenes to reveal how it all happened."Gary Myers, former NFL columnist Dallas Morning News, New York Daily News, and New York Times bestselling author of Brady vs. Manning and How 'Bout Them Cowboys?

-

"Bob Glauber has done a magnificent job capturing these three Hall of Fame Coaches, Joe Gibbs, Bill Parcells and Bill Walsh and a great era of the NFL. A must-read."Charley Casserly, former GM of the Washington Redskins and Houston Texans

-

"The extraordinary careers of these coaches are expertly interwoven to create a delightful and insightful read."Library Journal

-

"Glauber shows in fascinating detail how each coach built a foundation for success both on the field and in their relationships with owners and players. This has been a great season for football books...and this one adds to the treasure trove."Booklist

- On Sale

- Nov 20, 2018

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781549194801

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use