Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

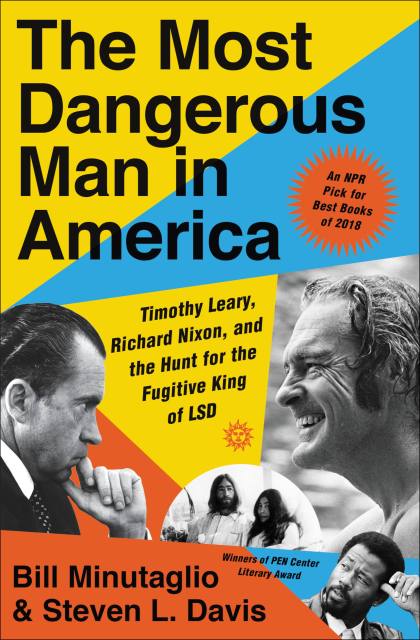

The Most Dangerous Man in America

Timothy Leary, Richard Nixon and the Hunt for the Fugitive King of LSD

Contributors

By Steven L. Davis

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $23.49 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 9, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

On the moonlit evening of September 12, 1970, an ex-Harvard professor with a genius I.Q. studies a twelve-foot high fence topped with barbed wire. A few months earlier, Dr. Timothy Leary, the High Priest of LSD, had been running a gleeful campaign for California governor against Ronald Reagan. Now, Leary is six months into a ten-year prison sentence for the crime of possessing two marijuana cigarettes.

Aided by the radical Weather Underground, Leary’s escape from prison is the counterculture’s union of “dope and dynamite,” aimed at sparking a revolution and overthrowing the government. Inside the Oval Office, President Richard Nixon drinks his way through sleepless nights as he expands the war in Vietnam and plots to unleash the United States government against his ever-expanding list of domestic enemies. Antiwar demonstrators are massing by the tens of thousands; homemade bombs are exploding everywhere; Black Panther leaders are threatening to burn down the White House; and all the while Nixon obsesses over tracking down Timothy Leary, whom he has branded “the most dangerous man in America.”

Based on freshly uncovered primary sources and new firsthand interviews, The Most Dangerous Man in America is an American thriller that takes readers along for the gonzo ride of a lifetime. Spanning twenty-eight months, President Nixon’s careening, global manhunt for Dr. Timothy Leary winds its way among homegrown radicals, European aristocrats, a Black Panther outpost in Algeria, an international arms dealer, hash-smuggling hippies from the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, and secret agents on four continents, culminating in one of the trippiest journeys through the American counterculture.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jan 9, 2018

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781455563609

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use