By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

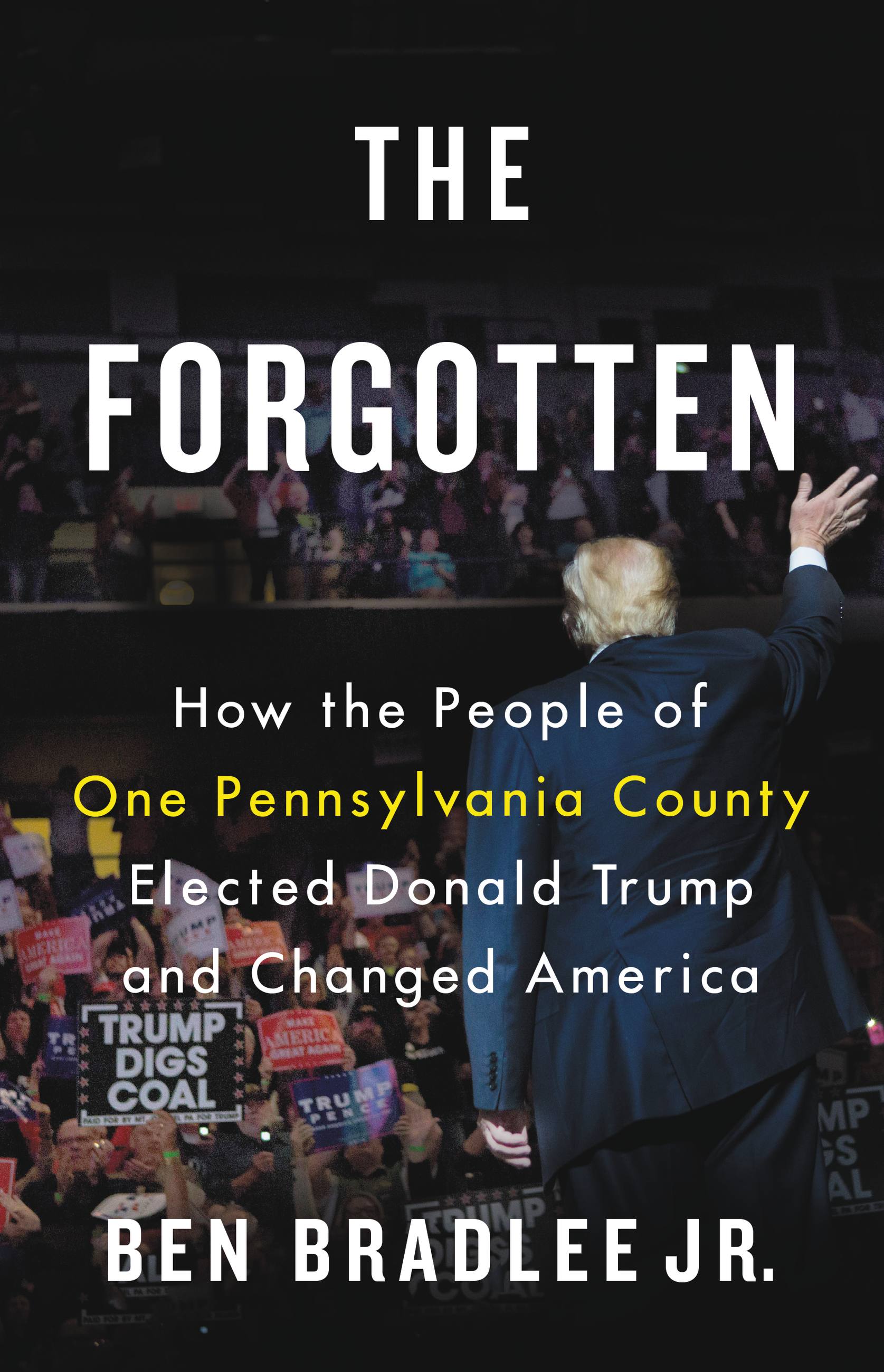

The Forgotten

How the People of One Pennsylvania County Elected Donald Trump and Changed America

Contributors

By Ben Bradlee

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 2, 2018

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316515719

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 2, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The people of Luzerne County, Pennsylvania voted Democratic for decades, until Donald Trump flipped it in 2016. What happened?

Named one of the “juiciest political books to come in 2018” by Entertainment Weekly.

In The Forgotten, Ben Bradlee Jr. reports on how voters in Luzerne County, a pivotal county in a crucial swing state, came to feel like strangers in their own land – marginalized by flat or falling wages, rapid demographic change, and a liberal culture that mocks their faith and patriotism.

Fundamentally rural and struggling with changing demographics and limited opportunity, Luzerne County can be seen as a microcosm of the nation. In The Forgotten, Trump voters speak for themselves, explaining how they felt others were ‘cutting in line’ and that the federal government was taking too much money from the employed and giving it to the idle. The loss of breadwinner status, and more importantly, the loss of dignity, primed them for a candidate like Donald Trump.

The political facts of a divided America are stark, but the stories of the men, women and families in The Forgotten offer a kaleidoscopic and fascinating portrait of the complex on-the-ground political reality of America today.

Named one of the “juiciest political books to come in 2018” by Entertainment Weekly.

In The Forgotten, Ben Bradlee Jr. reports on how voters in Luzerne County, a pivotal county in a crucial swing state, came to feel like strangers in their own land – marginalized by flat or falling wages, rapid demographic change, and a liberal culture that mocks their faith and patriotism.

Fundamentally rural and struggling with changing demographics and limited opportunity, Luzerne County can be seen as a microcosm of the nation. In The Forgotten, Trump voters speak for themselves, explaining how they felt others were ‘cutting in line’ and that the federal government was taking too much money from the employed and giving it to the idle. The loss of breadwinner status, and more importantly, the loss of dignity, primed them for a candidate like Donald Trump.

The political facts of a divided America are stark, but the stories of the men, women and families in The Forgotten offer a kaleidoscopic and fascinating portrait of the complex on-the-ground political reality of America today.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use