Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

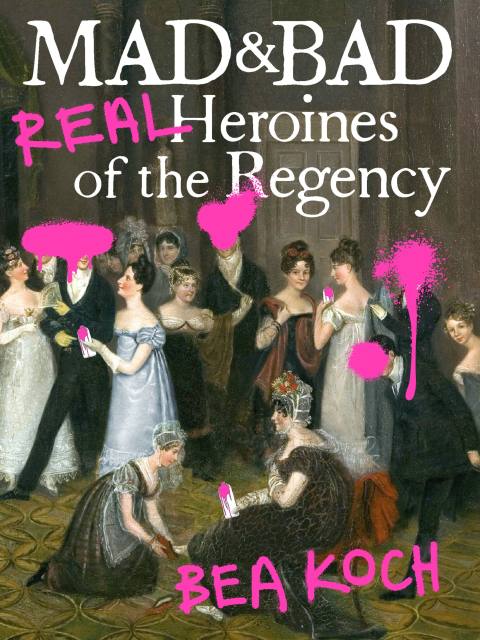

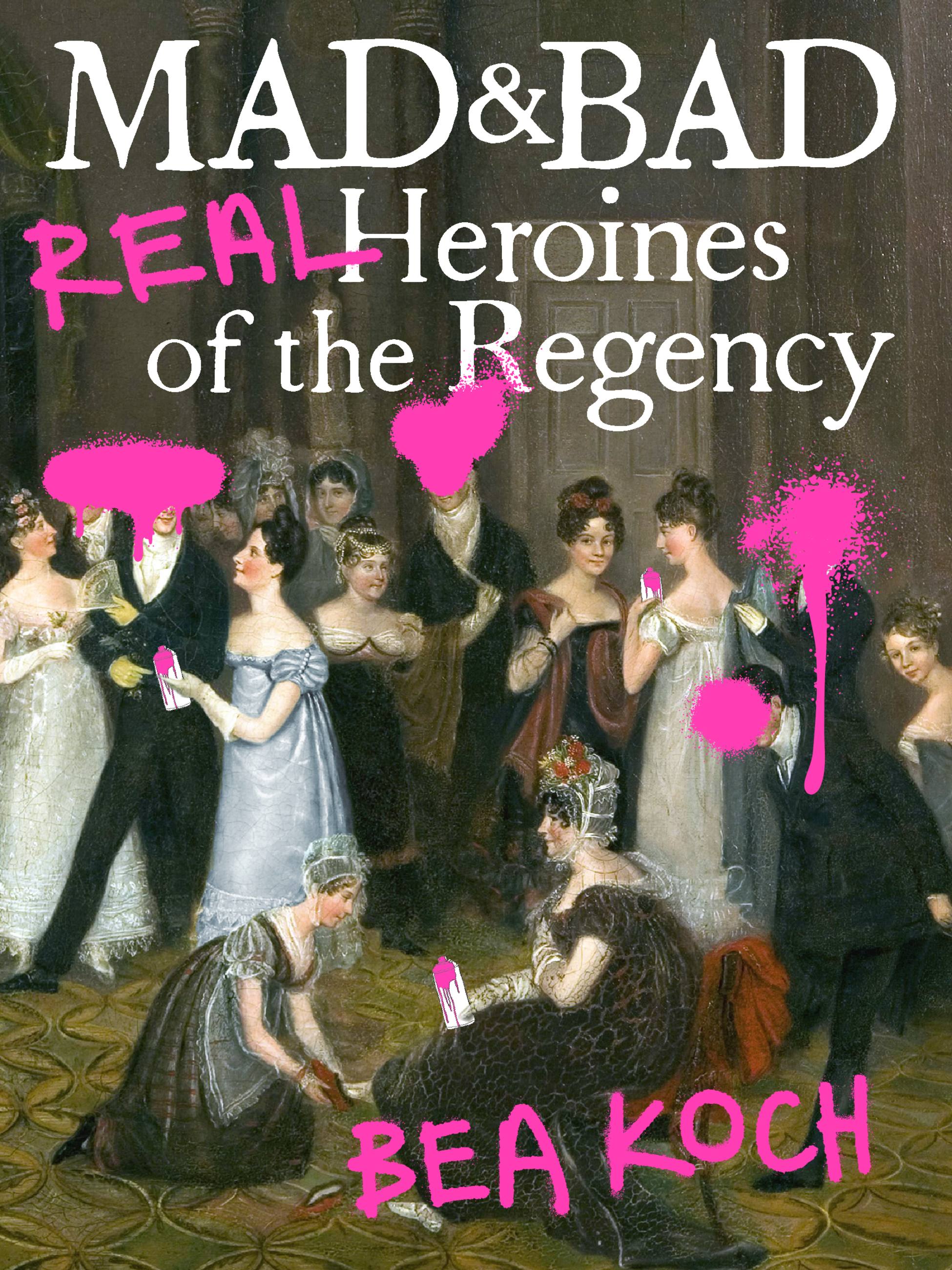

Mad and Bad

Real Heroines of the Regency

Contributors

By Bea Koch

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 1, 2020

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538701027

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Digital download $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 1, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

"Romance novel readers, Austenites, and Byronheads will love delving into the truth behind the aesthetics they've long adored."― Tori Telfer, author of Lady Killers

Regency England is a world immortalized by Jane Austen and Lord Byron in their beloved novels and poems. The popular image of the Regency continues to be mythologized by the hundreds of romance novels set in the period, which focus almost exclusively on wealthy, white, Christian members of the upper classes.

But there are hundreds of fascinating women who don't fit history books' limited perception of what was historically accurate for early 19th century England. Women like Dido Elizabeth Belle, whose mother was a slave but was raised by her white father's family in England, Caroline Herschel, who acted as her brother's assistant as he hunted the heavens for comets, and ended up discovering eight on her own, Anne Lister, who lived on her own terms with her common-law wife at Shibden Hall, and Judith Montefiore, a Jewish woman who wrote the first English language Kosher cookbook.

Bea Koch, one of the owners of the romance-only bookstore The Ripped Bodice, takes the Regency era and reveals the independent-minded, standard-breaking real historical women who lived life on their terms. She also examines broader questions of culture in chapters that focus on the LGBTQ and Jewish communities, the lives of women of color in the Regency, and women who broke barriers in fields like astronomy and paleontology.

In Mad and Bad, we look beyond popular perception of the Regency into the even more vibrant, diverse, and fascinating historical truth.

"I can only hope that Bea Koch decides to give us more books like this. With this book, she shines a spotlight on a group of women who deserve to live as more than footnotes in history … This is a book that deserves all the attention it can get." ―Culturess

"Koch vividly shines light on the queer, Jewish and women of color who have long been overlooked." ―Ms. Magazine

Genre:

-

"I can only hope that Bea Koch decides to give us more books like this. With this book, she shines a spotlight on a group of women who deserve to live as more than footnotes in history...This is a book that deserves all the attention it can get."Culturess

-

"With the popularity of TV shows and films set in Regency England, I'm thankful for Bea Koch and her examination of the era beyond the wealthy, white, Christian focus of the past. Koch vividly shines light on the queer, Jewish and women of color who have long been overlooked."Ms. Magazine

-

"This is not the Regency you thought you knew! Bea Koch's Mad & Bad is an important and enlightening new look at this classic era."Maya Rodale, bestselling author of historical romance

-

"Bea Koch presents a welcome assessment of the various forms of power and agency that women could wield in the male-dominated society of Regency England."Roy and Lesley Adkins, authors of Jane Austen's England

-

"Bea Koch's Mad and Bad is a marvelous work of joyful feminist triumph that paints a nuanced picture of the British Regency era as women experienced it. From Caroline Lamb to Annie Lister to Mary Seacole, Koch's lovingly rendered biographies illuminate fascinating narratives of power, inequity, ambition, and passion. What a gift to have at our fingertips this excellent archive of mad, bad heroines, all of whom demand bother remembrance and careful study. I will return to its pages often, grateful for the historical tapestry Koch has gracefully woven."Rachel Vorona Cote, author of Too Much

-

"As it turns out, the Regency Era wasn't just a world of Lord Byron-esque players and Mr. Darcy-esque dreamboats. There were women there, too -- gasp! -- and they were just as mad, bad, and dangerous to know. Koch Takes readers on a romp through some of the most fascinating ones, from scandalous rich women who took a lot of lovers to sisters who hunted fossils to a gal who earned herself the nickname "Gentleman Jack." Romance novel readers, Austenites, and Byronheads will love delving into the truth behind the aesthetics they've long adored."Tori Telfer, author of Lady Killers