Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

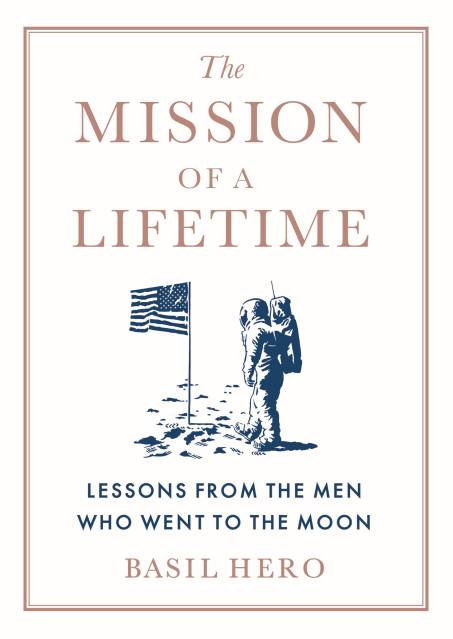

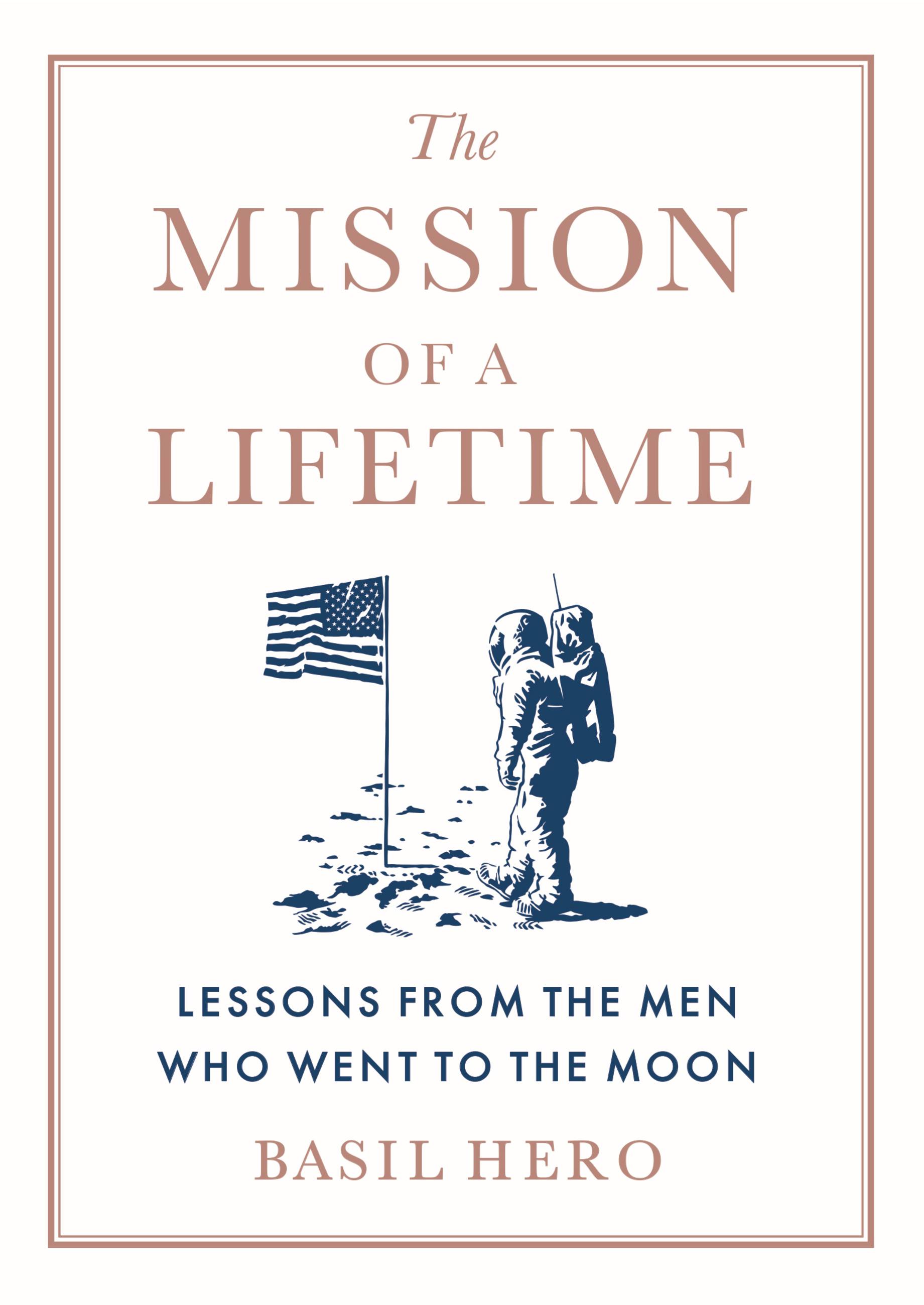

The Mission of a Lifetime

Lessons from the Men Who Went to the Moon

Contributors

By Basil Hero

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $37.00 $47.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 2, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Award-winning former investigative reporter Basil Hero chronicles the life lessons humanity can learn from the twelve remaining Apollo astronauts who went to the Moon.

In rare in-depth interviews, the twelve remaining lunar explorers, for the first time, talk at length about the real right stuff; the true source of courage, leadership, and the quiet patriotism that it took to risk their lives going to the moon. Hero begins each chapter with key life lessons that readers can gain from these honorable men whom he calls the Eagles. He describes how they mastered their emotions and learned to conquer their fears through techniques that can be used from the classroom to the boardroom.

More importantly their voyages to the Moon led them to the most incredible discovery of all: our home planet and its precious place in the universe. They fear for Earth’s future and offer sensible solutions to its mounting crises and the path to future space exploration.

In The Mission Of A Lifetime, the Eagles share their wisdom and urge us to reframe our view of Earth to theirs: no identifiable nations, borders, or races; just Earthlings working together as a collective civilization.

In rare in-depth interviews, the twelve remaining lunar explorers, for the first time, talk at length about the real right stuff; the true source of courage, leadership, and the quiet patriotism that it took to risk their lives going to the moon. Hero begins each chapter with key life lessons that readers can gain from these honorable men whom he calls the Eagles. He describes how they mastered their emotions and learned to conquer their fears through techniques that can be used from the classroom to the boardroom.

More importantly their voyages to the Moon led them to the most incredible discovery of all: our home planet and its precious place in the universe. They fear for Earth’s future and offer sensible solutions to its mounting crises and the path to future space exploration.

In The Mission Of A Lifetime, the Eagles share their wisdom and urge us to reframe our view of Earth to theirs: no identifiable nations, borders, or races; just Earthlings working together as a collective civilization.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 2, 2019

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538748503

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use