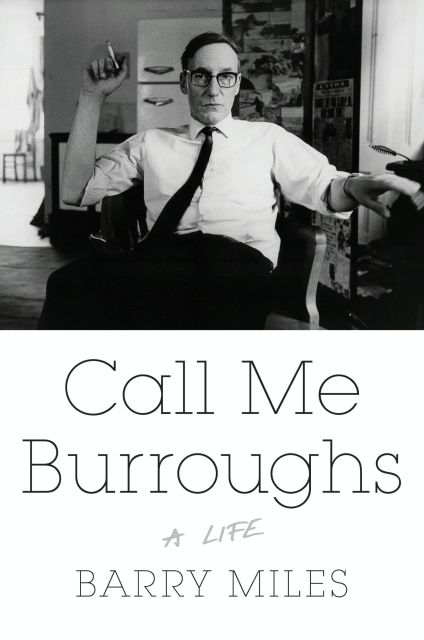

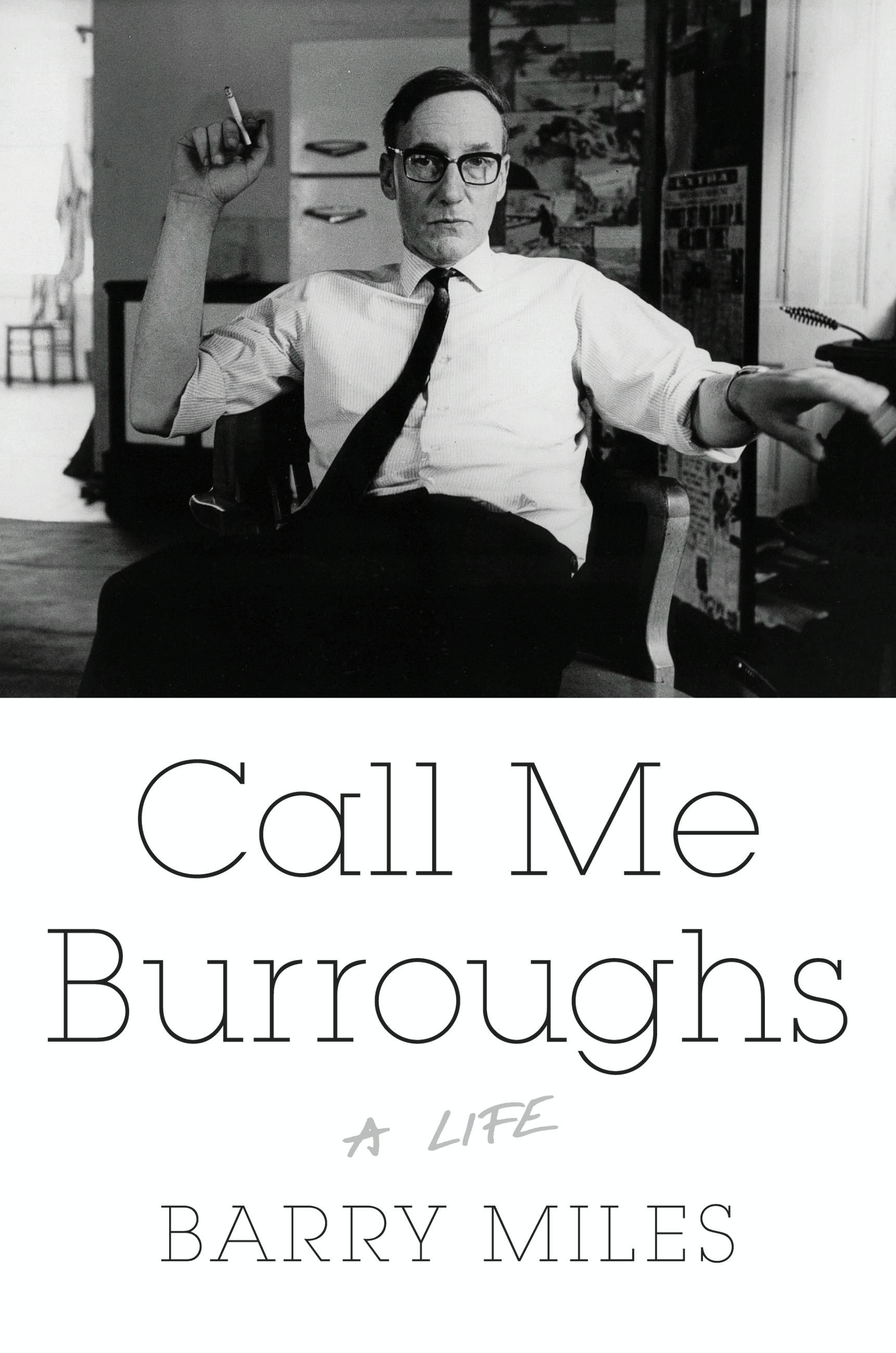

Call Me Burroughs

A Life

Contributors

By Barry Miles

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $20.00 $22.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 28, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Fifty years ago, Norman Mailer asserted, “William Burroughs is the only American novelist living today who may conceivably be possessed by genius.” Few since have taken such literary risks, developed such individual political or spiritual ideas, or spanned such a wide range of media. Burroughs wrote novels, memoirs, technical manuals, and poetry. He painted, made collages, took thousands of photographs, produced hundreds of hours of experimental recordings, acted in movies, and recorded more CDs than most rock bands. Burroughs was the original cult figure of the Beat Movement, and with the publication of his novel Naked Lunch, which was originally banned for obscenity, he became a guru to the 60s youth counterculture. In Call Me Burroughs, biographer and Beat historian Barry Miles presents the first full-length biography of Burroughs to be published in a quarter century-and the first one to chronicle the last decade of Burroughs’s life and examine his long-term cultural legacy. Written with the full support of the Burroughs estate and drawing from countless interviews with figures like Allen Ginsberg, Lucien Carr, and Burroughs himself, Call Me Burroughs is a rigorously researched biography that finally gets to the heart of its notoriously mercurial subject.

- On Sale

- Jan 28, 2014

- Page Count

- 736 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781455511945

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use