By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

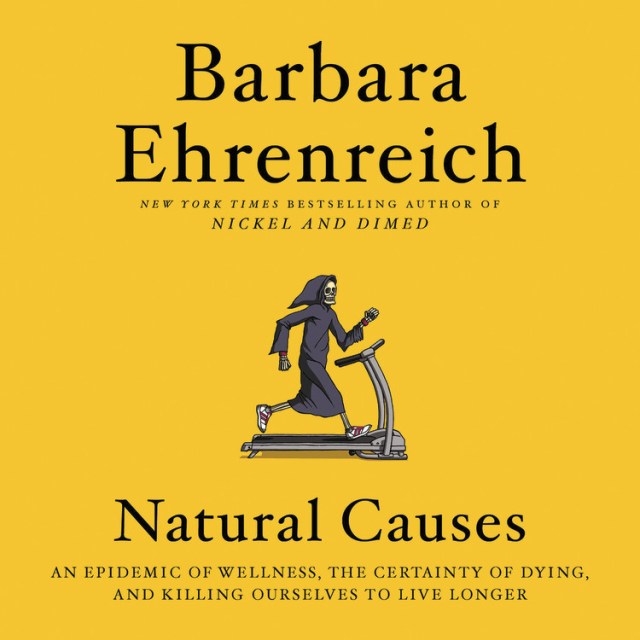

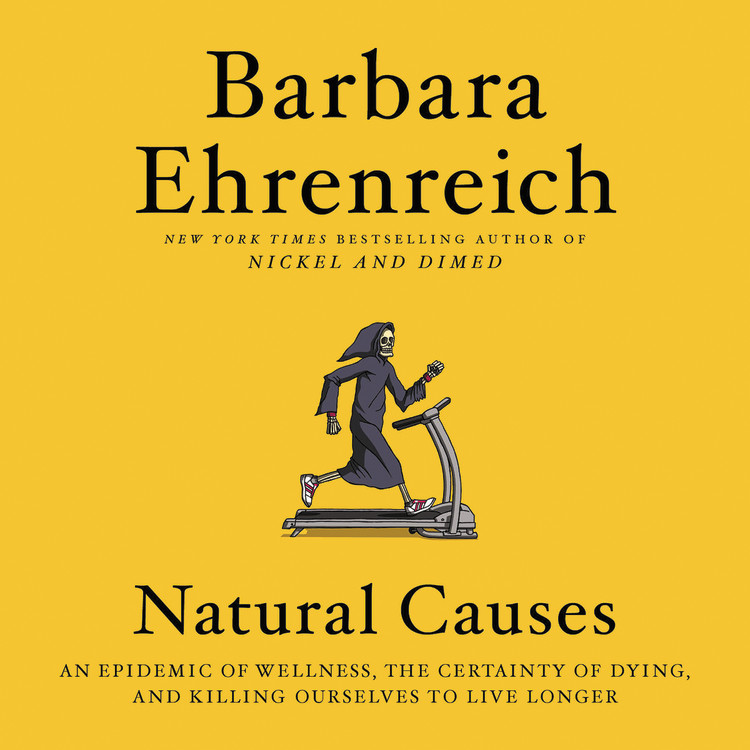

Natural Causes

An Epidemic of Wellness, the Certainty of Dying, and Killing Ourselves to Live Longer

Contributors

Read by Joyce Bean

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 10, 2018

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781478961260

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook $11.99 $14.99 CAD

- Hardcover (Large Print) $40.00 $50.00 CAD

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 10, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From the celebrated author of Nickel and Dimed, Barbara Ehrenreich explores how we are killing ourselves to live longer, not better.

A razor-sharp polemic which offers an entirely new understanding of our bodies, ourselves, and our place in the universe, Natural Causes describes how we over-prepare and worry way too much about what is inevitable. One by one, Ehrenreich topples the shibboleths that guide our attempts to live a long, healthy life — from the importance of preventive medical screenings to the concepts of wellness and mindfulness, from dietary fads to fitness culture.

But Natural Causes goes deeper — into the fundamental unreliability of our bodies and even our “mind-bodies,” to use the fashionable term. Starting with the mysterious and seldom-acknowledged tendency of our own immune cells to promote deadly cancers, Ehrenreich looks into the cellular basis of aging, and shows how little control we actually have over it. We tend to believe we have agency over our bodies, our minds, and even over the manner of our deaths. But the latest science shows that the microscopic subunits of our bodies make their own “decisions,” and not always in our favor.

We may buy expensive anti-aging products or cosmetic surgery, get preventive screenings and eat more kale, or throw ourselves into meditation and spirituality. But all these things offer only the illusion of control. How to live well, even joyously, while accepting our mortality — that is the vitally important philosophical challenge of this book.

Drawing on varied sources, from personal experience and sociological trends to pop culture and current scientific literature, Natural Causes examines the ways in which we obsess over death, our bodies, and our health. Both funny and caustic, Ehrenreich then tackles the seemingly unsolvable problem of how we might better prepare ourselves for the end — while still reveling in the lives that remain to us.

A razor-sharp polemic which offers an entirely new understanding of our bodies, ourselves, and our place in the universe, Natural Causes describes how we over-prepare and worry way too much about what is inevitable. One by one, Ehrenreich topples the shibboleths that guide our attempts to live a long, healthy life — from the importance of preventive medical screenings to the concepts of wellness and mindfulness, from dietary fads to fitness culture.

But Natural Causes goes deeper — into the fundamental unreliability of our bodies and even our “mind-bodies,” to use the fashionable term. Starting with the mysterious and seldom-acknowledged tendency of our own immune cells to promote deadly cancers, Ehrenreich looks into the cellular basis of aging, and shows how little control we actually have over it. We tend to believe we have agency over our bodies, our minds, and even over the manner of our deaths. But the latest science shows that the microscopic subunits of our bodies make their own “decisions,” and not always in our favor.

We may buy expensive anti-aging products or cosmetic surgery, get preventive screenings and eat more kale, or throw ourselves into meditation and spirituality. But all these things offer only the illusion of control. How to live well, even joyously, while accepting our mortality — that is the vitally important philosophical challenge of this book.

Drawing on varied sources, from personal experience and sociological trends to pop culture and current scientific literature, Natural Causes examines the ways in which we obsess over death, our bodies, and our health. Both funny and caustic, Ehrenreich then tackles the seemingly unsolvable problem of how we might better prepare ourselves for the end — while still reveling in the lives that remain to us.

-

"Ehrenreich's sharp and fearless take on mortality privileges joy over juice fasts and argues that, regardless of how many hours we spend in the gym, death wins out. An incisive, clear-eyed polemic, NATURAL CAUSESrelaxes into the realization that the grim reaper is considerably less grim than a life spent in terror of a fate that awaits us all."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Helvetica Neue'; color: #454545}Matthew Desmond, Pulitzer Prize-winning and New York Times bestselling author of Evicted

-

"...[A] provocative, informative, hilarious, and deeply moving book. A must read."Arlie Hochschild, New York Times bestselling author of Strangers in their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right

-

"Throughout the text, [Ehrenreich] employs the erudition that earned her degree, the social consciousness that has long informed her writing, and the compassion that endears her to her many fans...A powerful text that floods the mind with illumination-and with agonizing questions."Kirkus (starred review)

-

"[Ehrenreich] offers a healthy dose of reformist philosophy combined with her trademark investigative journalism. In assessing our quest for a longer, healthier life, Ehrenreich provides a contemplative vision of an active, engaged health care that goes far beyond the physical restraints of the body and into the realm of metaphysical possibilities."Booklist

-

"Barbara Ehrenreich is a singular voice of sanity amid our national obsession with wellness and longevity. She is deeply well-informed about contemporary medical practices and their shortcomings, but she wears her learning lightly. NATURAL CAUSES is a delightful as well as an enlightening read. No one who cares about living (or dying) well can afford to miss it."Jackson Lears, PhD, Editor in Chief of the Raritan Quarterly Review

-

"This book is joyous. It is neither anti-medicine nor anti-prevention; it is pro-balance, pro-scepticism and pro-perspective. Paradoxically, Natural Causes is about hope. If you are struggling with choices that weigh hope in potential medical advances that damage quality of life against non-treatment and the acceptance of a terminal diagnosis, this may not offer much comfort, but...as with so many of Ehrenreich's books, NATURAL CAUSES is a much-needed tonic."The Guardian

-

"'Give me a lever and a place to stand and I will move the earth,' promised Archimedes. In Natural Causes, Barbara Ehrenreich has achieved an Archimedean feat. Her lever is made of erudition, acuity and irreverence; her place to stand is the perspective of cultural criticism; and she has turned the current understanding of body and self upon its head. To read this book is a relief: at last, what needed to be said!"Jessica Riskin, author of The Restless Clock: A History of the Centuries-Long Argument over What Makes Living Things Tickp.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 27.0px; font: 21.0px Arial; color: #111111; -webkit-text-stroke: #111111; background-color: #ffffff}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

-

Claiming to be 'old enough to die,' feminist scholar Ehrenreich (Living with a Wild God) takes on the task of investigating America's peculiar approach to aging, health, and wellness...Ehrenreich's sharp intelligence and graceful prose make this book largely pleasurable reading."Publishers Weekly

-

"...[R]ichly layered with evidence, stories and quotations...and sprinkled with barbed humor. Ehrenreich lets nobody off the hook, skewering Silicon Valley meditators and misogynist obstetricians with equal vigor. It's impossible to read this book without questioning the popular wisdom about the body and its upkeep. At the very least, you'll be able to make better decisions about how to work out, whether to have that mammogram and when to just order the steak."BookPage

-

"[Ehrenreich's] description of cells rushing to staunch a wound is so full of wonder and delight that it recalls Italo Calvino...She sits in contemplation of death itself in the book's concluding, very beautiful passages, bringing to it her characteristic curiosity and awe at the natural world."The New York Times

-

"Ehrenreich proves a fascinating guide to the science suggesting that our cells, like the macrophages that sometimes destroy and sometimes defend, can act unpredictably and yet not randomly."The Atlantic

-

"[Ehrenreich] is one of our great iconoclasts, lucid, thought-provoking and instructive, never more so than here."Blake Morrison, The Guardian

-

"Informative, provocative and entertaining."The Times

-

"'Wham bam, thank you, ma'am' might be one response to this polemical, wry, hilarious and affecting series of counterintuitive essays by one of the most original and unexpected thinkers around...This is a book itself teeming with ideas and possibilities: maddening, stimulating, exciting and surprising, testifying in its own way to the expanding prospects of ideas that turn topsy-turvy, every-which-way as we try to make sense of the great unknowns."The Arts Desk

-

"Ehrenreich's observations about our culture-wide denial of bodily decay lead[s]...down distinct paths of interrogation and discovery. For all [her] research, [she is] not prepared to give us easy answers. Still...dry humor and raw, personal accounts help make thinking about our common fate bearable. We may have a few extra years yet to sip kale smoothies, run marathons and get tested for everything under the sun, but we ought not make physical health our ultimate hope."Wall Street Journal

-

"Engaging...Ehrenreich's scathing takedown of the wellness industry, New Age banalities and the epidemic of overdiagnosis will have you reconsidering how you live and die, and possibly second-guessing your next colonoscopy."Newsweek

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use